Model Perspective: BMW M1

Nội Dung Chính

Model Perspective: BMW M1

BMW’s Original M Car Left a Long, Colorful Legacy

Four decades of “M” history precede BMW’s current lineup of high-performance cars and SUVs wearing the M badge, but it’s understandable that not all M customers would immediately recognize the sub-brand’s “big bang” moment: the BMW M1.

Originally conceived for FIA silhouette racing series, with pure racers resembling production versions, the M1 became a racing orphan when that ended in 1980. That was just one of the roadblocks that nearly killed the car. In the end, BMW assembled only 399 M1 road cars and another four dozen or so racers.

At its inaugural auction at the Monterey Jet Center, Broad Arrow Auctions sold a numbers-matching 1981 BMW M1 for $692,500. Here’s the story of this significant but sometimes misunderstood BMW supercar.

The 1978 BMW M1 was the “big bang” moment for the automaker’s “M” performance brand. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

The 1978 BMW M1 was the “big bang” moment for the automaker’s “M” performance brand. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

Good Intentions

BMW Motorsports GmbH launched in 1972 as a semi-autonomous racing division within the company. The group became a major force in the European Touring Car Championship with the BMW 3.0 CSL coupe, which came to be known as the “Batmobile” for its wild mélange of aero body pieces.

As that car came to its conclusion in the mid-Seventies, founder and head of BMW Motorsports Jochen Neerpasch decided to build a mid-engine road/race car for the FIA’s new World Championship of Makes. Neerpasch hatched a plan to have Giorgetto Giugiaro’s Ital Design create a new body for a chassis that would house the inline-six from the CSL racer, detuned for road use or tweaked for racing. Things went a little squirrely from there.

The M1 may have had the smallest rendition of BMW’s trademark “twin kidney” grille. . (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

The M1 may have had the smallest rendition of BMW’s trademark “twin kidney” grille. . (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

A Sweet German-Italian Confection

BMW had no capacity to build 400 copies of the new car needed for FIA homologation, but guess who did? Lamborghini. The Italian supercar maker was in dire financial straits by the late Seventies, but perhaps the 400-car contract was thought to be enough of a lifeline. Alas, it wasn’t, and Lamborghini soon entered bankruptcy. That detour would lead down a bumpy road to several successive owners, including Chrysler at one point, and finally stopping at VW Group.

And so, it was on to plan B for the mid-engine BMW, but still an Italian-German mashup. Gianpaolo Dallara, who had designed the Lamborghini Miura’s chassis, created the tube frame for the M1, which used double-wishbone suspension front and rear. Marchese would build the frame, and a company called TIR would make the fiberglass body, which was just 45 inches tall yet offered a very hospitable cabin.

Ital Design assembled the body to chassis and installed the interior. The shell would then go to Baur in Stuttgart, which had a long partnership with BMW building prototypes and factory-sanctioned conversions of coupes to convertibles. BMW Motorsports conducted final assembly steps in Munich and gave the M1 its own manufacturing plate.

The BMW M1’s trunk has just enough space to squeeze in a bit of soft luggage. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

The BMW M1’s trunk has just enough space to squeeze in a bit of soft luggage. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

Its Own Racing Series

With no suitable race series for the M1 to enter, BMW Motorsport pitched an idea to Formula One for a one-marque support race. The Procar series was born in summer 1978, each grid featuring the top-five qualifiers from the Formula One race, along with 15 privateers in their own M1s.

This expensive undertaking turned BMW Motorsport into a full-on racecar manufacturer and servicer. The program got a public visual boost in 1979 when BMW commissioned Andy Warhol to make an M1 racer its fourth “art car.” The Procar series M1s were tweaked to 470 horsepower. The series ended in 1980, and so did M1 production.

BMW commissioned Andy Warhol to paint an M1 racer as the fourth of its famous “art cars.” (Source: BMW)

BMW commissioned Andy Warhol to paint an M1 racer as the fourth of its famous “art cars.” (Source: BMW)

Forbidden Fruit in America

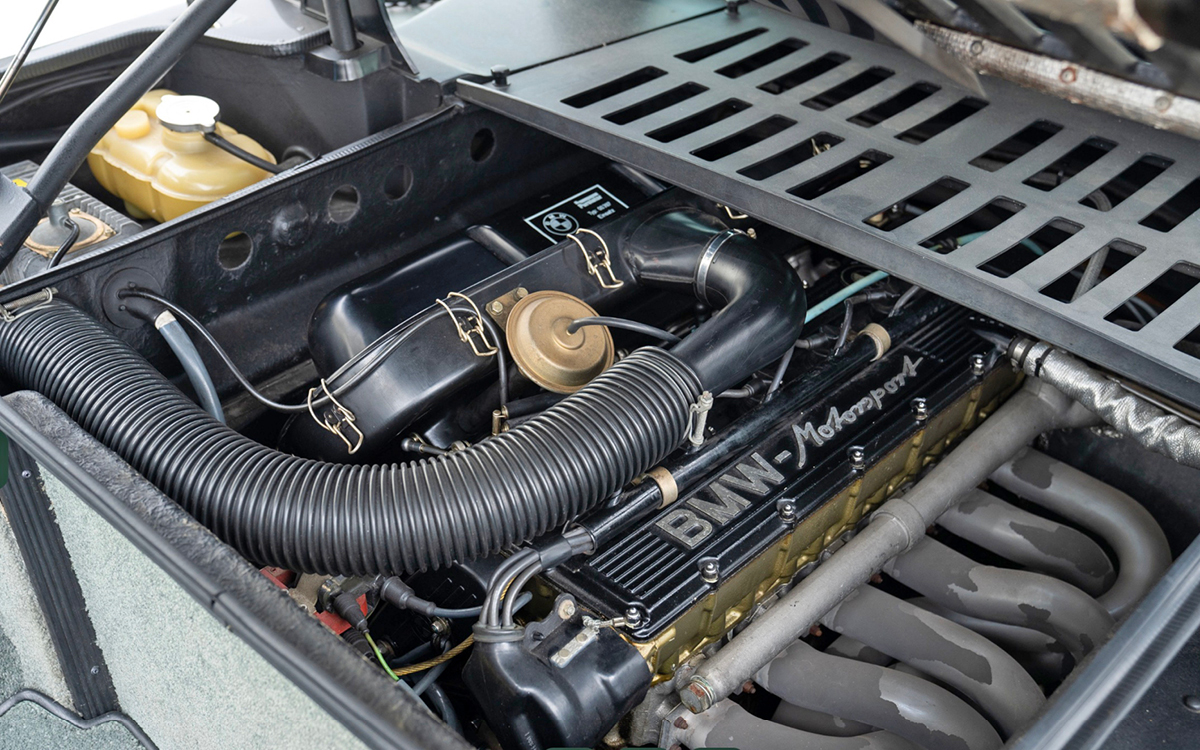

As a road car, the M1 was a stunner for the time. The double-overhead cam 3.5-liter inline six was a race engine at heart, with mechanical fuel injection using six individual throttles. A dry-sump lubrication system and crankshaft-triggered ignition were part of the package. If the M1’s 270 or so net horsepower seems tame today, remember, this was 1980. A five-speed manual was the sole transmission choice. If the M1’s leather and cloth interior appears no more upscale than the period’s 5 Series, that was to keep things simple, functional and comfortable.

The M1 was never certified for the U.S. But Car and Driver managed to test a privately imported customer’s car just before it was sent to Hardy & Beck in Berkeley, California for “federalization,” when the DOT/EPA still allowed such activity. The 3,000-pound M1 zoomed from zero to 60 in 5.4 seconds and reached 100 mph just 8 seconds later. Top speed was 160 mph. This was stellar performance at the time, leading the magazine to refer to the M1 in terms that might today seem like hyperbole:

“The M1 is the absolute pinnacle of hyperfast street cars. Its overdoses of power and handling and responsiveness are suitably tempered by comfortable accommodation and a civilized ride. If a gentled-down race car can be made this good, then all the other ultracar builders are going about it from the wrong end.”

The M1’s 3.5-liter inline six was a race engine detuned for road use. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

The M1’s 3.5-liter inline six was a race engine detuned for road use. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

Room for two, but no room to recline the M1’s cloth seats. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

Room for two, but no room to recline the M1’s cloth seats. (Source: Broad Arrow Auctions)

A Long Legacy

BMW never had an incentive to continue the M1 program. One could argue that the original Acura NSX fulfilled the dream of an “everyday” supercar 10 years later. Also, BMW did revisit the mid-engine sports car idea quite successfully with the 2015-2020 i8 hybrid, building 20,400.

The M1, though, will always stand alone as the star that launched the BMW M brand.

Written by Jim Koscs, Audamotive Communications

Written by Jim Koscs, Audamotive Communications