History – Southern Ute Indian Tribe

Nội Dung Chính

Early History

The Ute people are the oldest residents of Colorado, inhabiting the mountains and vast areas of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Eastern Nevada, Northern New Mexico and Arizona. According to tribal history handed down from generation to generation, our people lived here since the beginning of time.

Prior to acquiring the horse, the Utes lived off the land establishing a unique relationship with the ecosystem. They would travel and camp in familiar sites and use well established routes such as the Ute Trail that can still be seen in the forests of the Grand Mesa, and the forerunner of the scenic highway traversing through South Park, and Cascade, Colorado.

The language of the Utes is Shoshonean, a dialect of that Uto-Aztecan language. It is believed that the people who speak Shoshonean separated from other Ute-Aztecan speaking groups, such as the Paiute, Goshute, Shoshone Bannock, Comanche, Chemehuevi and some tribes in California. The Utes were a large tribe occupying the great basin area, encompassing the Numic speaking territories of Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Eastern California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Northern Arizona and New Mexico.

Tribes living in this area, ancestors of the Utes were the Uto-Aztecs, who spoke one common language; they possessed a set of central values, and had a highly developed society. Traits commonly attributed to people possessing a civilization. The Ute civilization spoke the same language, shared values, observed the same social and political practices, in addition to inhabiting and holding a set territory.

The Utes settled around the lake areas of Utah, some of which became the Paiute, other groups spread north and east and separated into the Shoshone and Comanche people, and some traveled south becoming the Chemehuevi and Kawaiisus. The remaining Ute people became a loose confederation of tribal units called bands. The names of the bands and the areas they lived in before European contact are as follows:

The Mouache band lived on the eastern slopes of the Rockies, from Denver south to Trinidad, Colorado, and further south to Las Vegas, New Mexico.

The Caputa band lived east of the Continental Divide, south of the Conejos River and in the San Luis Valley near the headwaters of the Rio Grande. They frequented the region near Chama and Tierra Amarilla. A few family units also lived in the shadow of Chimney Rock, now a designated United States National Monument.

The Weenuchiu occupied the valley of the San Juan River and its north tributaries in Colorado and Northwestern New Mexico. The Uncompahgre (Tabeguache) were located near the Uncompahgre and Gunnison, and Elk Rivers near Montrose and Grand Junction, Colorado.

The White River Ute (Parianuche and Yamparika) lived in the alleys of the White and Yampa river systems, and in the North and middle park regions of the Colorado Mountains, extending west to Eastern Utah. The Uintah lived east of Utah Lake to the Uinta Basin of the Tavaputs plateau near the Grand and Colorado River systems.

The Pahvant occupied the desert area in the Sevier Lake region and west of the Wasatch Mountains near the Nevada boundary. They inter-married with the Goshute and Paiute in Southern Utah and Nevada. The Timonogots lived in the south and eastern area of Utah Lake, to North Central Utah. The Sanpits (San Pitch) lived in the Sapete Valley, Central Utah and Sevier River Valley. The Moanumts lived in the upper Sapete Valley, Central Utah, in the Otter Creek region of Salum, Utah and Fish Lake area; they also intermarried with the Southern Paiutes. The Sheberetch lived in the area now known as Moab, Utah, and were more desert oriented. The Comumba/Weber band was a very small group and intermarried and joined the Northern and Western Shoshone.

Today, the Mouache and Caputa bands comprise the Southern Ute Tribe and are headquartered at Ignacio, Colorado. The Weenuchiu, now known as the Ute Mountain Utes are headquartered at Towaoc, Colorado. The Tabeguache, Grand, Yampa and Uintah bands comprise the Northern Ute Tribe located on the Uintah-Ouray reservation next to Fort Duchesne, Utah.

As the Utes traveled the vast area of the Great Basin, large bands would breakup into smaller family units that were much more mobile. Camps could be broken down faster making travel from one location to another a more efficient process. Because food gathering was an immense task, the people learned that by alternating hunting and food gathering sites the environment would have time to replenish. The Nuche only took what they required, never over harvesting game or wild plants. These principles were closely adhered to in order for the people to survive.

In early spring and into the late fall, men would hunt for large game such as elk, deer, and antelope; the women would trap smaller game animals in addition to gathering wild plants such as berries and fruits. Wild plants such as the amaranth, wild onion, rice grass, and dandelion supplemented their diet. Some Ute bands specialized in the medicinal properties of plants and became expert in their use, a few bands planted domestic plants.

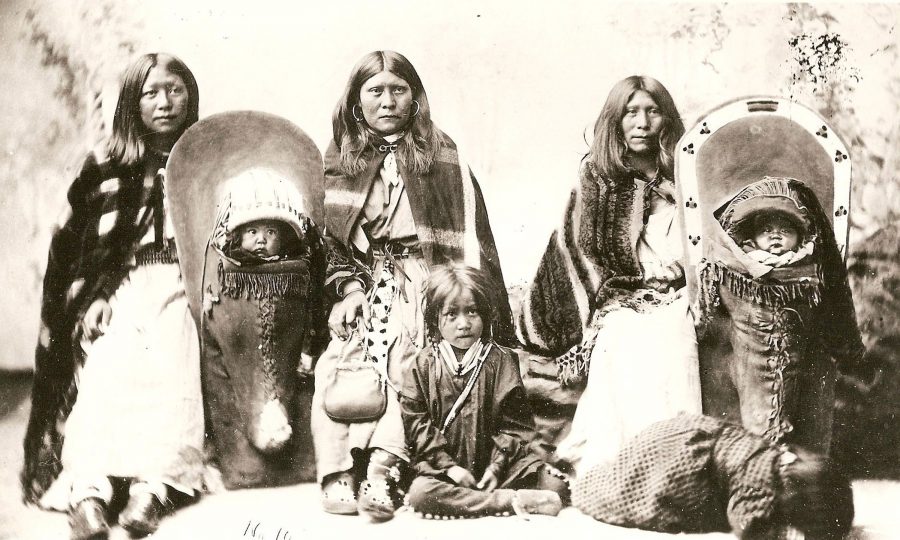

Before they acquired the horse, the Utes used basic tools and weapons which were made of stone and wood. These tools included digging sticks, weed beaters, baskets, bows and arrows, flint knives, arrow heads, throwing sticks, matates and manos for food preparation. They traded with the Puebloans for pottery to use for food and water storage and transport. They became very skilled at basket weaving, making coiled containers sealed with pitch for water storage. As expert hunters they used all parts of the animal. Elk and deer hides were used for shelter covers, clothing and moccasins. The hides the Utes tanned were prized and a sought after trade item. The Ute women became known for their beautiful quill work, which decorated their buckskin dresses, leggings, moccasins, and cradleboards.

Late in the fall, family units would begin to move out of the mountains into sheltered areas for the cold winter. Generally, the family units of a particular Ute band would live close together. The family units could acquire more fuel for heating and cooking. The increased family units would also allow for a better line of defense form enemy tribes seeking supplies for the harsh winter weather. The Caputa, Mouache and Weenuchiu wintered in northwestern New Mexico; the Tabeguache (Uncompahgre) camped near Montrose and Grand Junction; the Northern Utes would make their winter camps along the White, Green and Colorado Rivers.

Winter was a time of rejuvenation and the Utes would gather around their evening fires visiting and exchanging stories about their travels, social, and religious events. This was a time to reinforce tribal custom, as well as repairing tools, weapons and making new garments for the summer.

The Chiefs would announce plans for major events. A primary event that marked the beginning of spring was the annual Bear Dance. The Bear Dance is still considered a time of rejuvenation by the tribe. It is in essence, the Tribes’ New Year, when Mother Earth begins a new cycle, plants begin to blossom, animals come out of their dens after a long cold winter.

The Bear awakens from his winter’s sleep and celebrates by dancing to welcome the spring. This dance was given to the Ute people by the bear. The Bear Dance is the most ancient dance of the Ute people and continues to be observed by all Ute bands. When many of the various bands gathered for the Bear Dance it allowed relatives to socialize, while at the same time providing an opportunity for the young people to meet and for marriages to be negotiated. On the last day of the Bear Dance, the Sundance Chief would announce dates of the Sundance.

The Ute people lived in harmony with their environment. They traveled throughout Ute territory on familiar trails that crisscrossed the mountain ranges of Colorado. They came to know not only the terrain but the plants and animals that inhabited the lands. The Utes developed a unique relationship with the environment learning to give and take from Mother Earth.

They obtained soap from the root of the yucca plant. The yucca was used to make rope, baskets, shoes, sleeping mats, and a variety of household items. The three leaf sumac and willow were used to weave baskets for food and water storage. They learned how to apply pitch to ensure their containers were water-tight. They made baskets, bows, arrows, other domestic tools, and reinforcements for shade houses.

Chokecherry, wild raspberry, gooseberry, and buffalo berry were gathered and eaten raw. Occasionally juice was extracted to drink and the pulp was made into cakes or added to dried seed meal and eaten as a paste or cooked into a mush. Ute women would use seeds from various flowers or grasses and add them to soup. The three leaf sumac would be used in tea for special events.

The people would harvest roots with a tool called a digging stick. The digging stick was pointed and about three to four feet long. Roots collected were the sego (mariposa) lily, yellow pond lily, yampa or Indian carrot. The amaranth plant was gathered and the seeds were obtained with a tool called a seed beater, similar to winnowing. Amaranth seeds were often eaten raw, the Indian potato (Orogenia linearifolia) and wild onion were used in soups or eaten raw. They could be dried for later use or ground into a flour to make stews thicker. Utes would use earthen ovens to cook food. They would prepare the food items and place them into a four-foot deep hole lined with stones. A fire was built on top of the stones and the food was placed in layers of damp grass and heated rocks. These items would then be covered with dirt to cook over night. The prickly pear cactus was another food source. The flower and fruit were either eaten raw or boiled or roasted.

The inner bark of the tree is very nutritious and was yet another food source for the people. The Utes harvested the inner bark of the ponderosa pine for making healing compresses, tea and for healing. The scarred ponderosa trees are still visible in Colorado forests. The healing trees are evidence of the Utes early presence in the land and their close relationship to their ecosystem.

When the Ute people were forcibly placed reservations they could no longer travel on their familiar trails, to gather or hunt for food. As more and more elders pass they take traditional knowledge about plants and their uses with them. In the past the Ute vocabulary included many words and their uses for plants. Unfortunately, these ancient words have been lost.

A medicinal plant used by the Utes is Bear root (Ligusticum portieri) also commonly known as osha. Bear root grows throughout the Rocky Mountains, in elevations over 7,000 feet. The plant has antibacterial and antiviral powers and continues to be used to treat colds and upper respiratory ailments. It can be chewed or brewed into teas. It can be used topically, in baths, compresses, and ointments to treat indigestion, infections, wounds and arthritis. Some southwest tribes use it before going into the desert areas to deter rattlesnakes. The Utes have a special relationship with the plant and treat it with great respect, harvesting only what they need and always giving prayers before they harvest.

Ute elders knew which plants should be gathered and which plants were dangerous. One has to be very careful when harvesting wild plants as many toxic plants can be mistaken for wild onion or bear root. Poison hemlock (Conium macalatum) appears much the same as the bear root but is dangerous. Peppermint and wild tobacco were collected and used in many important ceremonies.

The routes the Utes established were used by other Native American tribes and Europeans. The Ute Trail became known as the Spanish Trail used by Spanish explorers as early as the fifteenth century when Alvar Nunez Caveza de Vaca (1488-1558) and Juan de Onate (1550-1630) were sent from Spain to explore the uninhabited areas of Texas and New Mexico, claiming vast lands for their Spanish rulers.

During the sixteenth century Spaniards began to colonize New Mexico, establishing their domination wherever possible. As the Spanish advanced northward into Ute territory, the customs, livestock, and language they brought began to influence the Ute’s way of life. These changes were to have far reaching impacts upon the Ute people. Not only did the European bring livestock and tools, they also brought small pox, cholera and other diseases that would decimate the population of the Ute people. The European’s never-ending quest for land was in direct contrast to the Native American’s reverence for Mother Earth. The Utes believed that they didn’t own the land, but that the land owned them. Contact with the European was to end a way of life the people had known for centuries.

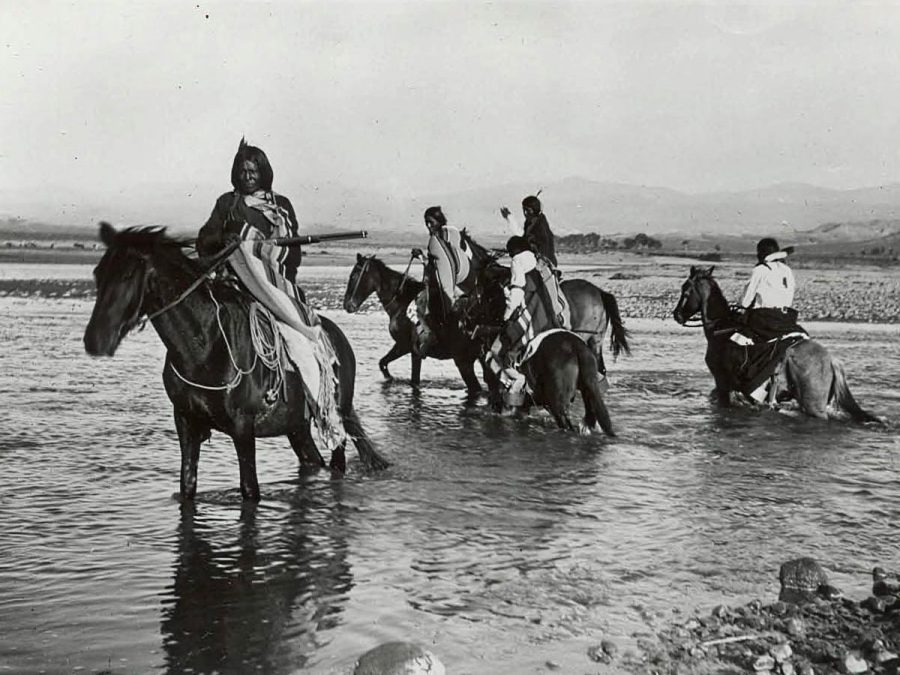

Contact between the Southern Utes and the Spanish continued, with trade soon developing. Utes were known for their tanned elk and deer hides which they traded along with dried meat tools and weapons. However, as the Spanish became more aggressive conflicts began to arise. When Santa Fe was established as the northern capital of the Spanish colonists they captured Utes and other Native Americans as slave laborers to work in their fields and homes. Around 1637 Ute captives escaping from the Spanish in Santa Fe fled, taking with them Spanish horses, thus making the Utes one of the first Native American tribes to acquire the horse. However, tribal historians tell of the Utes acquiring the horse as early as the 1580s.

Already skilled hunters, the Utes used the horse to become expert big game hunters. They began to roam further away from their home camps to hunt buffalo that migrated over the vast prairies east of their mountain homes, and explore the distant lands.

The Utes began to depend upon the buffalo as a source for much of their items. It took only one buffalo to feed several families, and fewer hides were required to make structures and clothing.

The Utes already had a reputation as defenders of their territories now became even fiercer warriors. Women and children were also fierce and were known to pick up a lance and defend their camps from attacking enemies. Ute men were described by the Spanish as having fine physiques, able to withstand the harsh climate, and live off the land in sharp contrast to the European who often had to depend upon Native Americans and their knowledge about plants, animals and the environment. They became adept raiders preying upon neighboring tribes such as the Apache, Pueblos and Navajo. Items obtained from their raids were used to trade for household items, weapons, horses and captives. Owning horses increased one’s status in the tribe.

Encounters with the Spanish began to occur more frequently, and trade increased to include Spanish items such as metal tools and weapons, cloth, beads and even guns. The bounty collected from raiding expeditions was used to trade for horses, which were considered a valuable commodity. Captives from raids were also used as barter items.

In November 1806 Zebulon Pike entered the eastern boundaries of Ute lands proclaiming one of the Ute’s most sacred sites as “Grand Peak”, now known as Pike’s Peak. Prior to this, Ute territory had not been explored on a large scale because of the rugged terrain and high mountain passes. Europeans began to take notice of the land’s bounty, timber, wildlife and abundant water. What they did not take into account was that the land was already inhabited by the Ute people, who considered the land their home.

As westward expansion increased and eastern tribes were displaced and relocated to barren lands in the west, pioneers began to travel west. Gold and silver were discovered in the San Juan Mountains and the Utes soon found themselves in a losing battle to retain their homelands.

Treaties and Agreements with the Utes

In the 1700s the Ute and Comanche tribes began peace negotiations to ensure peace between two powerful tribal allies that reigned over the southwestern plains, however, peace talks were interrupted and a fifty-year war followed. Peace talks began again and in 1977 the Ute Comanche Peace Treaty was finalized. Representatives of the Comanche Tribe traveled to Ignacio, Colorado to finalize the Ute Comanche Peace Treaty.

On December 30, 1849 a peace treaty was signed between the United States and the Utes at Abiquiu, New Mexico. The treaty forced the Utes to officially recognize the sovereignty of the United States and established boundaries between the U.S. and the Ute nation.

In 1863 another treaty was signed at Conejos terminating all Ute claims to mineral rights and lands in the San Luis Valley that had been settled by Europeans.

In 1868 the U.S. government began another treaty to terminate the rights of the Confederated Ute Indians to other lands; however this effort failed as the Utes refused to relinquish their rights to the lands in question. In 1873 the government began new efforts to negotiate for these lands and a new commission was appointed by the Interior in 1873 to enter into negotiations for a new agreement. The Brunot agreement of 1873 was negotiated with the Confederated Utes and the U.S. government, represented by Felix R. Brunot, at the Los Pinos Agency on September 13, 1873. Ute chiefs, headmen and other members of the Tabeguache, Mouache, Caputa, Weenuchiu, Yampa, Grand River and Uintah bands of Ute Indians were present when the Agreement was signed.

The Brunot Treaty was ratified by the United States in 1874, and is most often remembered by Utes as the agreement when their land was fraudulently taken away. The Utes were led to believe that they would be signing an agreement that would allow mining to occur on the lands located only in the San Juan Mountain area, the site of valuable gold and silver ore. About four million acres of land not subject to mining would remain Ute territory under ownership of the tribe. However, they ended up forcibly relinquishing the lands to the U.S. government. Many years later, and after meeting with the State of Colorado, a successful negotiation of a Memorandum of Agreement was signed in 2009. The MOA assured the tribe with hunting and fishing rights in the off-reservation Brunot area, including rare game species. Tribal hunters participate in the hunt with special permits.

In 1895 the Hunter Act was passed opening up the Ute strip to homesteading and sale to non-Indians. The Utes residing on the small strip of reservation land north of the New Mexico state boundary and into the four corners area became divided. The Weenuchiu under the leadership of Chief Ignacio agreed that land could not be owned individually, but instead was owned in commonality by tribe. The Weenuchiu moved westward and settled on a dry arid piece of land now known as Towaoc. The Southern Utes (Mouache and Caputa bands) agreed to take land into ownership under the allotment process. Unfortunately many allotments were either sold to non-Indians or the tribe. Around the 1940s about 300 allotments were owned by Southern Ute Tribal heads of household. This number has dwindled considerably.

Ute Water Rights

As the federal government established sites (reservations) for displaced Native American tribes, the government soon realized they had to have adequate water supplies in order to survive. Without water the red man could not learn how to farm and become a productive member of society, or become totally assimilated into American culture. Although there is an implied water right of Native American tribes on reservations that supersedes water rights of non-Indians, the issue was bitter, and proved to be a long and expensive legal battle.

In 1988 the Colorado Ute Indian Water Rights Settlement Act was approved by the United States government. Its primary objective was to supply irrigation, municipal and industrial water to the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute Tribes of Colorado from the Animas La Plata water project. The downsized project known as Animas Plata light was completed in 2009 and water filled Nighthorse Reservoir. The 1988 Act resolved water rights claims of the Colorado Ute Tribes to water they considered inherently theirs. The Ute tribes have not yet formulated specific plans concerning their water needs, and there are no federal funds available to construct the pipelines necessary to convey water from Nighthorse Reservoir to either the Ute Mountain Ute or Southern Ute reservations.

Ute Chieftains Memorial

On September 24, 1939, the Ute Chieftains Memorial Monument was dedicated in honor of four Ute Chiefs, Ouray, Buckskin Charley, Severo and Ignacio. The Southern Ute tribe which is comprised of the Caputa and Mouache bands progressed under the auspices of Chief Ouray and Buckskin Charley. Because of the endeavors of these fine leaders a memorial was created that now stands in Ute Park along the Los Pinos River in Ignacio, Colorado.

The memorial is comprised of red and white stone excavated from the Durango, Colorado area. The monument itself stands eighteen feet tall, it is eight feet square at its base, and is five feet square at the top. Four bronze plaques are set facing each of the four directions. Each plaque is dedicated to a Ute leader.

The bronze plaque honoring Ouray was sponsored by the Durango Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution; Buckskin Charley’s plaque was sponsored by the Southern Ute Tribe; Severo’s plaque was sponsored by the Federal Employees of Ignacio; and Ignacio’s plaque was sponsored by the American Legion and Auxiliary and S. A. L. Squadron of Durango, CO.

The Southern Utes

The Southern Ute Tribe is composed of two bands, the Mouache and Caputa. Around 1848 Ute Indian Territory included traditional hunting ground s in Wyoming, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas. In 1868 a large reservation was established for the Southern Utes that covered the western half of Colorado consisting of 56 million acres. In 1873, after gold and silver was discovered in the San Juan Mountains, the Brunot Agreement was created. The Agreement substantially diminished Southern Ute lands, depriving the tribe of seasonal camps, and annual elk and deer harvests. Around 1895 the Southern Ute reservation was created. It was 15 miles wide and 110 miles long. In 1895 the Hunter Act enabled lands within the Ute Strip to be allotted to tribal members, and the surplus lands homesteaded and sold to non-Indians.

The Southern Ute reservation consists of timberlands on high mountains with elevations over 9,000 feet in the eastern portion, and flat arid mesas on the west. Seven rivers run through the reservation, the Piedra, San Juan, Florida, La Plata, Animas, Navajo and Los Pinos. Water is a valuable resource, and its ownership became a central issue between the Ute people and non-Indians who lived on fee lands on the checker boarded Southern Ute Reservation and for the Ute Mountain people who were surrounded by non-Indians who deprived them of water for their people. The conflicts were ultimately settled by the 1988 Ute Water Rights Settlement Act.

The Southern Ute Tribe has approximately 1,400 tribal members, with half the population under the age of 30. The Southern Ute Reservation is situated on a 1,064 square mile (681,000 acres) reservation. The tribe is governed by a seven member Tribal Council elected by the membership. Principle officers include the Chairman, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer, with all council members serving three-year staggered terms. Tribal government is based on a Tribal Constitution adopted November 4, 1936, that was revised in September 1975. Although the tribe strives to provide strong social welfare and education programs, they also emphasize the importance of the traditional way of life. They sponsor the annual Sun Dance and Bear dance. Tribal members of all ages participate in Pow-wows. Tribal Council recognized the importance of traditional healing and has incorporated this method into the health services program.

Tribal government includes the Executive staff (Tribal Council, Executive Officers and support staff), administrative personnel, natural resources, education, utilities, judicial branch, health and social services, a culture department, and many more departments. In 2001 Sun Ute Community Center opened its doors. It houses a gymnasium, fitness center, and swimming pools, all at no charge to the tribal members. The center also houses the local Boys and Girls club.

The Southern Ute Tribal Academy opened in August 2000. The Academy is a private school that provides education and day care for children from the ages of six months to the sixth grade. Its curriculum includes a comprehensive Ute language program.

At one time the Town of Ignacio as well as the surrounding land around the town was owned by Southern Ute tribal members. There are a few private homes owned by tribal members within town limits. Shoshone Town Park is tribal land leased by the Town of Ignacio; the Southern Ute Education offices are located within city limits, as is the Tribal Housing entity and rental homes located on reservation lands that border town limits.

Many tribal members lived in and around the Ignacio area in the early 1900s on up to the 1950s, and others lived on the reservation outside of town. Housing sites were established in the 1970’s under the Federal Department of Housing and Urban development (HUD), one of the many programs established to alleviate poverty in cities and on Indian reservations. Under HUD, rental and private housing was constructed, however, as federal housing budget cuts increased the tribe sought ways to assist tribal members in obtaining affordable housing. This resulted in a new housing development called Cedar Point Housing sub-division, financed in part by the Southern Ute Tribe, with qualifying tribal members purchasing homes. Cedar Point East began as rental units and converted to tribal member owned homes. Cedar Point West is comprised of privately owned homes, modular and trailer homes. There is still a constant demand for affordable homes for the membership.