These 7 maps shed light on most crucial areas of Amazon rainforest

Editor’s note: Between now and March, Conservation News is exploring the complexities of living in, using and protecting one of the planet’s most valuable types of ecosystems — tropical forests — in a series we’re calling “No forests, no future.” This is the first post in this series.

If you have never visited it, the world’s most famous forest may inspire visions of dense, pristine forest, thundering waterfalls — and very few humans.

In fact, the Amazonia region — which encompasses parts of nine countries in South America and includes both the Amazon rainforest and the water-rich Guiana Shield — is home to 30 million people, including 375 indigenous groups. It contains the largest tropical forest in the world, the richest biodiversity on the planet, almost one-third of the world’s tropical forest carbon and one-fifth of the planet’s fresh water that flows into the ocean.

People near and far rely on Amazonia’s ecosystems for everything from climate regulation to fisheries and food security. But despite these crucial services, ongoing deforestation and climate change impacts threaten to permanently alter this massive system — drying it up, decimating its biodiversity and slowing the flow of benefits to its people to a trickle.

If we want to prevent irreversible damage, we must first figure out what parts of Amazonia we can’t afford to lose.

In 2016, Conservation International led a project to map “essential natural capital” — the most important areas for biodiversity and ecosystem services — in order to identify which areas within Amazonia should be prioritized for conservation to ensure sustainable economic development.

By combining environmental, social and economic data using computer models, our maps (some of which appear below) are painting a more complete but disquieting picture regarding the health of — and threats to — these importance places.

Nội Dung Chính

1. Where the forests are — and where they’re disappearing

Map of forest cover (2010) and forest loss (2010-2014) in the Amazonia region. (map produced by Conservation International)

“Mapping where the forests are in Amazonia is a necessary first step to conserving them. However, it is equally important to identify where forests are being lost and why,” says Max Wright, remote sensing specialist in Conservation International’s Moore Center for Science.

“Satellite data can provide this information across large areas, and scientific advances have allowed us to ‘zoom in’ with greater precision than ever before. From 2010 to 2014, Amazonia lost almost 62,000 square kilometers (almost 24,000 square miles) of forest — equivalent to destroying a forest larger than Massachusetts every year.

“We identified hotspots of deforestation activity in southern Brazil, parts of Bolivia and along the Andean foothills in Peru. Although causes vary by geography, the expansion of agriculture — especially for soy and cattle — and increased human pressures are the primary drivers.”

2. Where the forests’ most effective guardians live

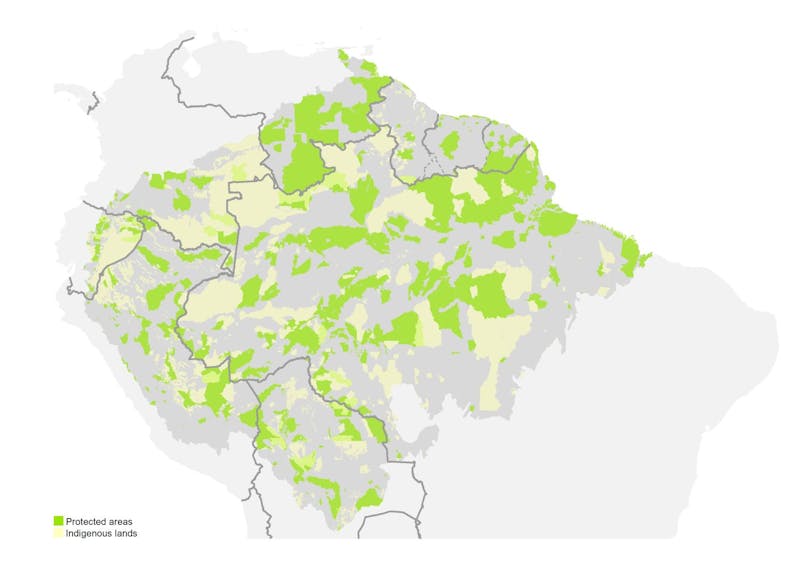

Map of protected areas (green) and indigenous lands (yellow) in the Amazonia region. (map produced by Conservation International)

“Indigenous people and local communities have been stewards of their lands and resources for thousands of years,” explains Lisa Famolare, vice president for Conservation International’s Amazonia program. “They also play a fundamental role in global forest conservation.

“As you can see in this map, protected areas and indigenous territories collectively encompass 46 percent of Amazonia. Local people depend on the region’s ecosystems for everything from food to income to protection from severe flooding. Unfortunately, the region’s 375 ethnic groups and their lands are also facing unprecedented threats due to rapid infrastructure development, the migration of outsiders into historically indigenous lands and conversion of forest for agriculture and other land uses.

“Partnering with indigenous peoples to conserve their lands and territories is a proven means of avoiding deforestation in Amazonia. For example, in Brazil Conservation International helped the Kayapó conserve over 10 million hectares (almost 25 million acres) of their forest in the Amazon. In Guyana, we’ve worked with the Wai Wai to help them conserve 350,000 hectares (865,000 acres) of pristine tropical forest, creating the country’s first indigenous community conserved area.”

3. The biggest biodiversity stronghold

Map of areas identified as priorities for conserving the Amazonia region’s wealth of biodiversity. (map produced by Conservation International)

Biodiversity — the variety of species and ecosystems that comprise all life on Earth — underpins all the benefits nature provides to people. In Amazonia, we mapped essential areas for biodiversity in two ways.

First, we collected maps of biodiversity priority areas that have already been identified by others. We found that only around half of these priority areas fall within protected areas and indigenous lands — which means that half of the world’s most important places for biodiversity have no formal protection.

Second, we conducted our own analyses based on IUCN Red List data for 4,220 species of mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles to identify places important for “endemic” species that are unique to Amazonia, or have relatively small ranges. If these natural areas are lost, these species will disappear from the planet.

We found that around 27 percent of the most important areas for endemic species are contained within protected areas, and 20 percent fall within indigenous lands. Thus there are still many critical endemic species habitats that remain unprotected.

4. Places that supply fresh water for people

Map of freshwater services (including drinking water and hydropower) currently benefiting people in the Amazonia region. Darker blue areas are the most important; black squares are cities and yellow triangles are dams. (map produced by Conservation International)

“The Amazon River and its tributaries provide food, transportation and water for domestic use and energy production, among other benefits,” says Natalia Acero, a water and cities fellow with Conservation International.

“For this study, we mapped ecosystems that play a role in the provision of freshwater services, such as forests, floodplains, lakes and river channels that provide flow regulation and water quality maintenance. This map shows areas that are already providing services to people or economic sectors, such as population centers and hydropower facilities.

“The darker blue areas on this map reflect ecosystems that support a relatively high provision of water for hydropower production (water quantity), avoided erosion and sedimentation (water quality) or provide a stable flow of water (flow regulation).

“Hydropower has the unique position of being both a service people depend on and a threat to the conservation of ecosystems. There are currently at least 171 hydroelectric dams operating or under construction in the region, providing energy to major cities in South America. The Amazon region accounts for 6 percent of global hydropower resources. However, dam construction has a massive impact on water flow within the Amazon basin, and can be considered the biggest threat to the hydrological connectivity of Amazonian rivers.”

5. Forests that store the most carbon

Carbon stock stored in the forests of Amazonia. Darker orange areas store more tons of carbon per hectare. (map produced by Conservation International)

“In the battle to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and curb global climate change, tropical forests play an important role,” Max Wright explains. “The Amazon rainforest acts as the ‘lungs of the Earth,’ absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and helping to regulate the global climate.

Recent studies suggest that conserving and restoring tropical forests could provide at least 30 percent of the solution to climate change. Forests store carbon while they are alive, sequester carbon as they grow and release carbon when they are cut down or burned. This means that if you conserve forests you are getting a triple benefit — or more accurately, two benefits and an avoided cost!

“This map reveals that the areas with the highest forest carbon stock are located in undisturbed parts of the central Amazon Basin and the remote portions of the northern Amazon Basin and Guiana Shield.

“The value of tropical forests for maintaining a stable healthy climate cannot be understated. And since the Amazon rainforest is the biggest of the bunch, what happens here will affect the entire globe.”

6. Areas most vulnerable to climate change impacts

Map identifying which regions of Amazonia are likely the most vulnerable to climate change impacts. (map produced by Conservation International)

“Droughts and floods are among the most severe climate change-related impacts already taking place in Amazonia, and are predicted to become stronger and more frequent due to climate change,” reports Paula Ceotto, director of corporate sustainability for Conservation International Brazil.

“To predict the likelihood of floods and droughts within Amazonia and how people will be affected by them, we examined a range of factors, including population density, access to education, income levels, current land uses and precipitation levels.

“We found that the foothills of the Andes are particularly vulnerable, as this area is characterized by steep slopes and is highly prone to an increase in water flow, which can cause flooding. Northeastern Brazil is also vulnerable due to its high population density, a predicted reduction in water availability in this area, and the relatively low adaptive capacity of its people due to low socioeconomic status.”

7. Amazonia’s ‘essential natural capital’

Map depicting where Amazonia’s ‘essential natural capital’ — the most important areas for biodiversity and ecosystem services — is located. (map produced by Conservation International)

Conservation International defines “essential natural capital” as areas that provide crucial benefits for people in the form of biodiversity, climate mitigation and adaptation, freshwater services and non-timber forest products. For Amazonia, our team combined them in a single map, and then calculated that 41 percent of essential natural capital is currently protected as indigenous lands and/or protected areas. Thus, a considerable percentage of Amazonia’s essential natural capital is already under legal designation. However, given that agricultural expansion, hydropower dam construction, climate change and other pressures continue to threaten the region, ongoing protection is not guaranteed.

Conservation International has the ambitious goal of achieving zero net deforestation in Amazonia by 2020. Alongside actions such as planting trees in degraded areas and improving the land efficiency of agriculture, conserving healthy standing forests is a crucial part of this process. By showing scientists, policymakers, companies and communities which areas are the most essential to protect, these maps are helping to prevent irreversible damage to a place that makes all life on Earth possible.

Rachel Neugarten is the director of conservation priority setting in Conservation International’s Moore Center for Science.

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Donate to Conservation International.

Further reading