The People’s History of American English

American English has been evolving ever since North America itself was founded. Through its various twists and turns and unexpected evolutions, English has become the language we now know and love. Here’s an in-depth look at the language’s every iteration, from the year 1600 up through the present day.

Nội Dung Chính

Discover the story:

Early America: The settlement history of American English language

It’s well-established that America was founded during tumultuous times. Despite all their discontent with British rule, however, early Americans basically still spoke British-style English. Though he’s credited with initiating all of American literature, for example, Jamestown leader John Smith’s writing is virtually identical to that of his England-based colleagues. 17th century American English was subdued in its enthusiasm, too; dramas and other forms of fiction were eschewed in favor of more utilitarian (and often more spiritual) texts.

It wouldn’t be until the 18th century that North American English began to grow independent from its English predecessor. Spurred on by thought leaders like Ben Franklin, whose Poor Richard’s Almanac was filled with “prudent and witty aphorisms” attributed to his pseudonym, an undereducated but wise farmer named Richard Saunders, English slowly shifted towards a more playful approach. Fellow publisher Thomas Paine and others also adopted a more commonsensical writing style.

General American English and British English split

By around 1720, Americans had begun to notice that their evolving dialect was different from the ol’ mother tongue. The Scots and the Irish began to arrive in the United States, bringing new dialects and a distinctive accent. Swedish, Spanish, Dutch, and French speakers also began to arrive during the colonial era, helping shape new dialect areas throughout the colonies. It seemed as though American English was leaving certain aspects of British English behind, while at the same time welcoming new words from other cultures.

By the 1800’s, there were three distinct dialect areas with different pronunciations, but similar vocabulary: Northern (New York, New England, and due west), Southern (Virginia to Georgia, out to Louisiana and due west), and Midland (Pennsylvania and the lower Midwest). The map below shows a similar pattern for modern-day U.S. English speakers.

This evolution was primarily an intentional one, pushed along by people like Franklin, Paine, and other patriots. As Noah Webster would explain roughly 60 years later: “The reasons for American English being different than English English are simple […as] an independent nation, our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language as well as government.”

These new words and phrases created throughout the centuries, referred to as “Americanisms”, signified the split from our English forefathers. As early as 1735, the English began to refer to American English, and our “Americanisms”, as barbaric, sneering and laughing at the hundreds of new American terms being used. It’s believed the American Revolution was a turning point for embedding this new English, as rebels fiercely desired their independence from British rule.

One way American English began to differ from its British version? By continuing to use words that Great Britain had come to consider obsolete, like “wilt,” “allow,” “bureau,” and “fall” (instead of “autumn”). In other situations, we Americans just invented new words, like “groundhog” and “belittle,” which was first coined by Thomas Jefferson.

American English also came to be characterized by heavy use of contractions like “can’t” and “ain’t” — much to the dismay of certain British purists, who viewed these changes as “barbarous.” Contractions had been around for a while by this point (‘won’t’ had taken the form of ‘wonnot’ by 1580), but Americans were the first to really make the most of them, using these shortened phrases to improve both grammatical freedom and flow.

American English also gladly adopted words from other languages, among them more than a few (like moose, raccoon, and opossum) from different Native American tongues. Words were borrowed from the languages of Spanish, French, and German immigrants, too: armada from the Spanish, chocolate from the French, dollar and ouch! from the Germans.

Examples of common English words and origin:

Cigar → Spanish

Cookie → Dutch

Metropolis → Greek

Safari → Arabic

By 1756 the differences between American and British English were pronounced enough that Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language was able to single out and criticize what Johnson called “the American dialect.” Johnson’s dictionary also had a noticeable, if not comical, British bent; it defined oats as “a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people” and highlighted a rather rudimentary method of timekeeping by some Americans, who “counted their years by the coming of certain birds amongst them at their certain seasons, and leaving them at others.”

Most American’s didn’t mind or complain — to them, such dialectic differences were just one more facet of their newfound independence.

Early works: The rise of American English

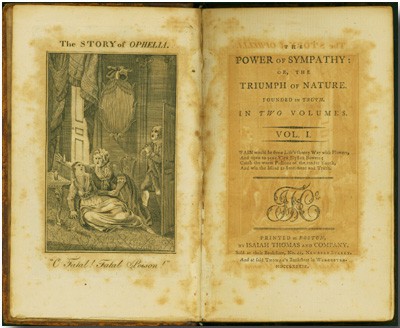

In 1789 the first American novel was produced: The Power of Sympathy, by William Hill Brown. Poet Philip Freneau brought American poetry to life with a romantic writing style that shined through works such as “The Indian Burying Ground,” “The Wild Honey Suckle,” and “On a Honey Bee.” And native-born writer Washington Irving was so good that even British critics approved of his work, which included fun-yet-refined novels like The Salmagundi papers, A History of New York, Diedrich Knickerbocker, The Sketch Book, and Bracebridge Hall. Irving pioneered the use of symbolism and imagery, and practically invented the short story.

Then came Edgar Allen Poe, whose psychological novels thrilled audiences and whose detective stories initiated a whole new genre. Poe was a skillful poet, too, as evidenced by the 1845 success of The Raven. By the turn of the nineteenth century, non-spiritual dramas and novels were finally accepted as valid forms of literature in America.

The Wild West… and its wild language

The evolution of America’s English was also catalyzed by the physical movement of its people. As huge swaths of Americans moved away from the East’s refined cities and into the West’s great unknown, their language tended to relax into something less refined, too. A survey of the era’s newspapers and other texts reveals that sometimes words were simply spelled exactly as they sounded — regardless of proper spelling! And most settlers probably retained the regional dialects of their homelands for a while, of course, at least until everything blended together into a wild-Western melting pot.

Traces of Western slang remain to this day. Though the horses and buggies of old are long gone, Americans west of the Mississippi are still more apt to say “baby buggy” than “baby carriage” or other alternatives. Words like “buckaroo” and “gunnysack” have also stuck around. Other phrases that got their start in the Wild West include “ace in the hole,” “hog killin’ time,” and, appropriately enough, “ambush.”

19th century American English grammar evolution

Deeply enriched by the earlier works of Mark Twain, the turn of the 19th century saw American literature — and American grammar — enter a sort of golden age. Authors turned to their words to express a growing distaste for the growing power of capitalism, monopolies, and government overreach. Many of these authors took an anti-authoritarian approach to their grammar, too, forgoing conventional grammar ‘rules’ in favor of a more avante-garde style.

But the 19th century also saw English grammar rise to its most refined levels yet, both in terms of its grammatical standards and its perceived importance. In 1864, this article published in the Journal of the Early Republic tells us, “‘grammar school’ referred to an elite institution that taught the classics’…an institution decidedly out of the average person’s reach. Yet by 1900 “‘grammar school’ had become synonymous with ‘elementary school’ in the United States […].” Proper grammar had come to be seen as something for everyone. As a result, the average American’s reading and writing skills went up considerably.

The 19th century witnessed the creation of thousands of new words, too, many of them related to science and medicine. “We need very much a name to describe a cultivator of science in general,” Victorian scientist William Whewell wrote in 1840. “I should incline to call him a Scientist.” Words like ‘biology,’ ‘climatology,’ and other ‘-ologies’ were also introduced around this time.

The General American Language

American grammar is also graced with its fair share of forgotten words and pronunciations — the road that led us to the present moment has been a pretty winding one!

“We are struck by the oddness of speech in earlier America,” noted this New York Times piece in 2012; oddities included using ‘sich’ in place of ‘such’ and ‘guv’ in place of ‘gave.’ These forgotten eccentricities even showed up in newspaper writing: the Chicago Tribune of 90 years ago included uniquely phonetic spellings like ‘crum,’ ‘heven’ and ‘iland.’ Grammatical differences between now and then also abound. Back then ‘hopefully’ wasn’t used as a sentence-starter, nor were the noun+phrase names of today (‘podcaster Rich Roll’ or ‘presidential hopeful Joe Biden’) en vogue.

American English continued to solidify itself, and by the 1920s the differences between it and British English inspired some to differentiate the two for good. In 1923 Illinois passed this distinction into law. A proponent of the “American Language” bill, congressman Washington J. McCormick encouraged other lawmakers to begin the “mental emancipation of ’23” and let American writers “drop their top-coats, spats, and swagger-sticks, and assume occasionally their buckskin, moccasins, and tomahawks.” Sounds like quite the patriot!

Between 1900 and 1999 around 185,000 new words drifted into the English language, based on the Oxford English Dictionary’s records. Inventions that we might take for granted today (like cars and airplanes) necessitated equally inventive language; interestingly enough, many car-related terms originated out of France, which was a leader in the automobile space. All in all, the 20th century saw the English language experience a 25% expansion — if only based on the number of words in circulation.

Today, American English has many different dialectics. People speak differently in the South, New England, and the Midwest, as well as local areas such as New York City or Virginia. You can break these American dialects down even further, such as the way people speak in Boston or New Orleans. Black English, a vernacular coined by American linguist J.L. Dillard, is also considered a dialect with its own grammatical structure and etymology.

Modern American English

Most modern trends begin with some sort of pre-modern trickle, and the evolution of English grammar is no exception. Think of that modern predisposition of using the word ‘like’ to structure everything (you know, like, kind of like this!) — isn’t that strictly a modern thing?

Well, sort of. But a fictional character named Tommy Wilhelm was guilty of overusing the word ‘like’ as early as 1956, in Saul Below’s Seize the Day. Move back to the present time and our collective use of ‘like’ has become truly ubiquitous. According to this in-depth analysis by The Atlantic, it’s also become specialized; one may encounter reinforcing likes, quotative likes, like, LOL’s, and more.

And though U.S. English grammar may be more unified now than it was in its earlier days, many different American English accents still persist.

Here are some of the highlights, courtesy of the 2016 book Speaking American:

- Most Americans say “you guys,” but Southerners much prefer “y’all.”

- Is it called “soda,” “pop,” or “coke”? That depends on where you live…

- Southerners pronounce words like “lawyer” differently than the rest of us — they say law-yur, not loy-er.

- Philadelphians call them hoagies, New Yorkers call them heroes…but most Americans just call them subs.

- Most Americans call major roads “highways,” but those along the West coast like the term “freeway” better.

As Richard W. Bailey attested in his book Speaking American, “those who seek stability in English seldom find it [and] those who wish for uniformity become laughingstocks.”

Where American English grammar is headed

Now that you know the history of the English language, here’s the thing: English grammar continues to change. It’s actually still evolving as we speak! Some say it’s de-volved at the hands of forces as omnipresent as texting and the internet; others say its focus has been diluted by the large majority of speakers who use it as a second language.

We would disagree, however. English grammar is still alive and well; if anything, tools such as Writer’s Grammar Checker have only brought proper English even further into the mainstream. We’d say the language is so complex that there’s really no shame in leveraging all the grammatical help one can get. Expressing yourself in American English has likely never been easier.

Want to improve your American grammar skills today? Start a free Writer trial.