The Original Meanings of the “American Dream” and “America First” Were Starkly Different From How We Use Them Today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b2/d7/b2d7cef7-4a64-4adc-99cc-92fba2f75010/german-american-bund-web.jpg)

Stop any American on the street and they’ll have a definition of the “American Dream” for you, and they’ll probably have a strong opinion about the slogan “America First,” too.

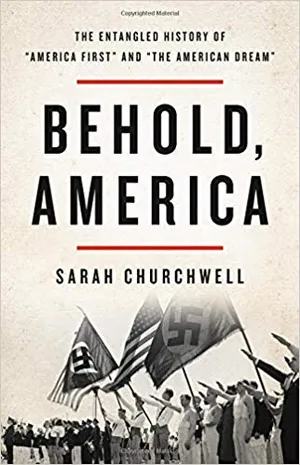

But how did Americans develop their understanding of these slogans? What did they mean when coined and how do the meanings today reflect those histories? That’s the subject of Sarah Churchwell’s upcoming book, Behold, America, out October 9. Introduced more than a century ago, the concepts of “American Dream” and “America First” quickly became intertwined with race, capitalism, democracy, and with each other. Through extensive research, Churchwell traces the evolution of the phrases to show how the history has morphed the meaning of the “American Dream” and how different figures and groups appropriated “America First.”

A Chicago native now living in the United Kingdom, Churchwell is a professor of American literature and public understanding of the humanities at the University of London. She spoke with Smithsonian.com about the unfamiliar origins of two familiar phrases.

Behold, America

In “Behold, America,” Sarah Churchwell offers a surprising account of twentieth-century Americans’ fierce battle for the nation’s soul. It follows the stories of two phrases—the “American dream” and “America First”—that once embodied opposing visions for America.

As a presidential candidate, Donald Trump used the slogan “America First,” which many people traced to Charles Lindbergh in the 1940s. But you trace its origin even further back.

I found the earliest use of the phrase as a Republican slogan in the 1880s, but it didn’t enter the national discussion until 1915, when Woodrow Wilson used it in a speech arguing for neutrality in World War I. That isn’t the same as isolationism, but the phrase got taken up by isolationists.

Wilson was treading a very fine line, where there were genuine and legitimate conflicting interests. He said he thought America would be first, not in the selfish spirit, but first to be in Europe to help whichever side won. Not to take sides, but to be there to promote justice and to help rebuild after the conflict. That was what he was trying to say in 1915.

“America First” was the campaign slogan not only of Wilson in 1916, but also of his Republican opponent. They both ran on an “America First” platform. Harding [a Republican] ran on an “America First” platform in 1920. When [Republican President Calvin] Coolidge ran, one of his slogans was “America First” in 1924. These were presidential slogans, it was really prominent, and it was everywhere in the political conversation.

How did “America First” become appropriated to have a racist connotation?

When Mussolini took power in November 1922, the word “fascism” entered the American political conversation. People were trying to understand what this new thing “fascism” was. Around the same time, between 1915 and the mid 1920s, the Second Klan was on the rise.

Across the country, people explained the Klan, “America First” and fascism in terms of each other. If they were trying to explain what Mussolini was up to, they would say, “It’s basically ‘America First,’ but in Italy.”

The Klan instantly declared “America First” one of its most prominent slogans. They would march with [it on] banners, they would carry it in parades, they ran advertisements saying they were the only “America First” society. They even claimed to hold the copyright. (That wasn’t true.)

By the 1930s, “America First” stopped being a presidential slogan, and it began to be claimed by extremist, far-right groups and who were self-styled American Fascist groups, like the German American Bund and the Klan. When the America First Committee was formed in 1940, it became a magnet that attracted all of these far-right groups that had already affiliated themselves with the idea. The story about Lindbergh and the Committee suggests that the phrase cropped out of nowhere, but that just isn’t the case.

You found that the backstory of “the American Dream” is also misunderstood.

“The American Dream” has always been about the prospect of success, but 100 years ago, the phrase meant the opposite of what it does now. The original “American Dream” was not a dream of individual wealth; it was a dream of equality, justice and democracy for the nation. The phrase was repurposed by each generation, until the Cold War, when it became an argument for a consumer capitalist version of democracy. Our ideas about the “American Dream” froze in the 1950s. Today, it doesn’t occur to anybody that it could mean anything else.

How did wealth go from being seen as a threat to the “American Dream” to being an integral part of it?

The “American Dream” really starts off with the Progressive Era. It takes hold as people are talking about reacting to the first Gilded Age when the robber barons are consolidating all this power. You see people saying that a millionaire was a fundamentally un-American concept. It was seen as anti-democratic because it was seen as inherently unequal.

1931 was when it became a national catch phrase. That was thanks to the historian James Truslow Adams who wrote The Epic of America, in which he was trying to diagnose what had gone wrong with America in the depths of the Great Depression. He said that America had gone wrong in becoming too concerned with material well-being and forgetting the higher dreams and the higher aspiration that the country had been founded on.

[The phrase] was redefined in the 1950s, and seen as a strategy for soft power and for [commercializing] the “American Dream” abroad. It was certainly an “American Dream” of democracy, but it was a very specifically consumerist version that said “this is what the ‘American Dream’ will look like.” By contrast with the earlier version, which was focused on the principles of liberal democracy, this was very much a free market version of that.

How do the two phrases fit together?

When I began this research, I didn’t think of them as related. They both started to gain traction in the American political and cultural conversation discernibly around 1915. They then came into direct conflict in the late 1930s and early 1940s in the fight over entering World War II. In that debate, both phrases were prominent enough that they could become shorthand, where basically the “American Dream” was shorthand for liberal democracy and for those values of equality, justice, democracy, and “America First” was shorthand for appeasement, for complicity, and for being either an outright fascist or a Hitler sympathizer.

The echoes between 100 years ago and now are in many ways as powerful, if not more powerful, than the echoes between now and the post-war situation.

Why is the history of political slogans and clichés, like the “American Dream,” so important? What happens when we don’t understand the nuances of these phrases?

We find ourselves accepting received wisdoms, and those received wisdoms can be distorting and flat-out inaccurate. At best, they’re reductive and oversimplifying. It’s like the telephone game, the more it gets transmitted, the more information gets lost along the way and more you get a garbled version of, in this case, important understandings of the historical evolution and the debates surrounding our national value system.

Will these phrases continue to evolve?

“The American Dream” has long belonged to people on the right, but those on the left who are arguing for things like universal health care have a historical claim to the phrase, too. I hope that this history can be liberating to discover that these ideas that you think are so constricting, that they can only ever mean one thing—to realize that 100 years ago it meant the exact opposite.