The FBI and the American Gangster, 1924-1938 — FBI

Welcome to the World of Fingerprints

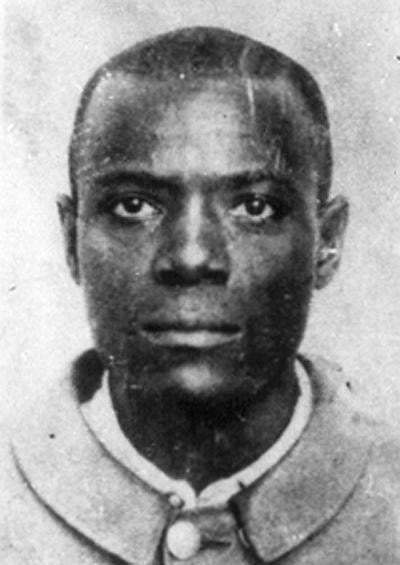

William West

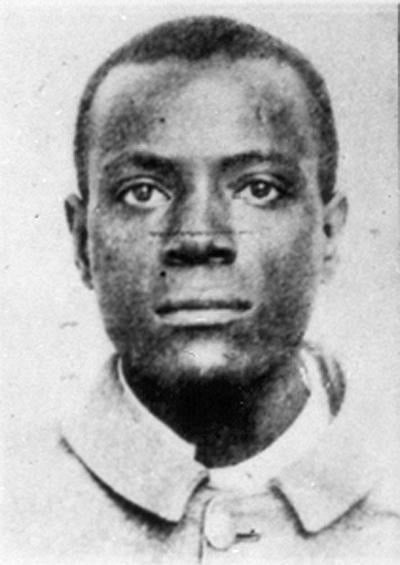

Will West

We take it for granted now, but at the turn of the twentieth century the use of fingerprints to identify criminals was still in its infancy.

More popular was the Bertillon system, which measured dozens of features of a criminal’s face and body and recorded the series of precise numbers on a large card along with a photograph.

After all, the thinking went, what were the chances that two different people would look the same and have identical measurements in all the minute particulars logged by the Bertillon method?

Not great, of course. But inevitably a case came along to beat the odds.

It happened this way. In 1903, a convicted criminal named Will West was taken to Leavenworth federal prison in Kansas. The clerk at the admissions desk, thinking he recognized West, asked if he’d ever been to Leavenworth. The new prisoner denied it. The clerk took his Bertillon measurements and went to the files, only to return with a card for a “William” West. Turns out, Will and William bore an uncanny resemblance (they may have been identical twins). And their Bertillon measurements were a near match.

The clerk asked Will again if he’d ever been to the prison. “Never,” he protested. When the clerk flipped the card over, he discovered Will was telling the truth. “William” was already in Leavenworth, serving a life sentence for murder! Soon after, the fingerprints of both men were taken, and they were clearly different.

It was this incident that caused the Bertillon system to fall “flat on its face,” as reporter Don Whitehead aptly put it. The next year, Leavenworth abandoned the method and start fingerprinting its inmates. Thus began the first federal fingerprint collection.

In New York, the state prison had begun fingerprinting its inmates as early as 1903. Following the event at Leavenworth, other police and prison officials followed suit. Leavenworth itself eventually began swapping prints with other agencies, and its collection swelled to more than 800,000 individual records.

By 1920, though, the International Association of Chiefs of Police had become concerned about the erratic quality and disorganization of criminal identification records in America. It urged the Department of Justice to merge the country’s two major fingerprint collections—the federal one at Leavenworth and its own set of state and local ones held in Chicago.

Four years later, a bill was passed providing the funds and giving the task to the young Bureau of Investigation. On July 1, 1924, J. Edgar Hoover, who had been appointed Acting Director less than two months earlier, quickly formed a Division of Identification. He announced that the Bureau would welcome submissions from other jurisdictions and provide identification services to all law enforcement partners.

The FBI has done so ever since.