The Deno Handbook: A TypeScript Runtime Tutorial with Code Examples

I explore new projects every week, and it’s rare that one grabs my attention as much as Deno did.

In this post I want to get you up to speed with Deno quickly. We’ll compare it with Node.js, and build your first REST API with it.

Nội Dung Chính

Table of contents

And note: You can get a PDF/ePub/Mobi version of this Deno Handbook here.

What is Deno?

If you are familiar with Node.js, the popular server-side JavaScript ecosystem, then Deno is just like Node. Except deeply improved in many ways.

Let’s start from a quick list of the features I like the most about Deno:

- It is based on modern features of the JavaScript language

- It has an extensive standard library

- It has TypeScript at its core, which brings a huge advantage in many different ways, including a first-class TypeScript support (you don’t have to separately compile TypeScript, it’s automatically done by Deno)

- It embraces ES modules

- It has no package manager

- It has a first-class

await - It has a built-in testing facility

- It aims to be browser-compatible as much as it can, for example by providing a built-in

fetchand the globalwindowobject

We’ll explore all of those features in this guide.

After you use Deno and learn to appreciate its features, Node.js will look like something old.

Especially because the Node.js API is callback-based, as it was written way before promises and async/await. There’s no change available for that in Node, because such a change would be monumental. So we’re stuck with callbacks or with promisifying API calls.

Node.js is awesome and will continue to be the de facto standard in the JavaScript world. But I think we’ll gradually see Deno get adopted more and more because of its first-class TypeScript support and modern standard library.

Deno can afford to have everything written with modern technologies, since there’s no backward compatibility to maintain. Of course there’s no guarantee that in a decade the same will happen to Deno and a new technology will emerge, but this is the reality at the moment.

Why Deno? Why now?

Deno was announced almost 2 years ago by the original creator of Node.js, Ryan Dahl, at JSConf EU. Watch the YouTube video of the talk, it’s very interesting and it’s a mandatory watch if you are involved in Node.js and JavaScript in general.

Every project manager must make decisions. Ryan regretted some early decisions in Node. Also, technology evolves, and today JavaScript is a totally different language than what it was back in 2009 when Node started. Think about the modern ES6/2016/2017 features, and so on.

So he started a new project to create some sort of second wave of JavaScript-powered server side apps.

The reason I am writing this guide now and not back then is because technologies need a lot of time to mature. And we have finally reached Deno 1.0 (1.0 should be released on May 13, 2020), the first release of Deno officially declared stable.

That’s might seem to be just a number, but 1.0 means there will not be major breaking changes until Deno 2.0. This is a big deal when you dive into a new technology – you don’t want to learn something and then have it change too fast.

Should you learn Deno?

That’s a big question.

Learning something new such as Deno is a big effort. My suggestion is that if you are starting out now with server-side JS and you don’t know Node yet, and have never written any TypeScript, I’d start with Node.

No one was ever fired for choosing Node.js (paraphrasing a common quote).

But if you love TypeScript, don’t depend on a gazillion npm packages in your projects and you want to use await anywhere, hey Deno might be what you’re looking for.

Will it replace Node.js?

No. Node.js is a giant, well established, incredibly well-supported technology that is going to stay around for decades.

First-class TypeScript support

Deno is written in Rust and TypeScript, two of the languages that are really growing fast today.

In particular, being written in TypeScript means we get a lot of the benefits of TypeScript even if we might choose to write our code in plain JavaScript.

And running TypeScript code with Deno does not require a compilation step – Deno does that automatically for you.

You are not forced to write in TypeScript, but the fact the core of Deno is written in TypeScript is huge.

First, an increasingly large percentage of JavaScript programmers love TypeScript.

Second, the tools you use can infer many information about software written in TypeScript, like Deno.

This means that when we code in VS Code, for example (which of course has a tight integration with TypeScript since both are developed at MicroSoft), we can get benefits like type checking as we write our code, and advanced IntelliSense features. In other words the editor can help us in a deeply useful way.

Similarities and differences with Node.js

Since Deno is basically a Node.js replacement, it’s useful to compare the two directly.

Similarities:

- Both are developed upon the V8 Chromium Engine

- Both are great for developing server-side with JavaScript

Differences:

- Node is written in C++ and JavaScript. Deno is written in Rust and TypeScript.

- Node has an official package manager called

npm. Deno does not, and instead lets you import any ES Module from URLs. - Node uses the CommonJS syntax for importing pacakges. Deno uses ES Modules, the official way.

- Deno uses modern ECMAScript features in all its API and standard library, while Node.js uses a callbacks-based standard library and has no plans to upgrade it.

- Deno offers a sandbox security layer through permissions. A program can only access the permissions set to the executable as flags by the user. A Node.js program can access anything the user can access.

- Deno has for a long time envisioned the possibility of compiling a program into an executable that you can run without external dependencies, like Go, but it’s still not a thing yet. That’d be a game changer.

No package manager

Having no package manager and having to rely on URLs to host and import packages has pros and cons. I really like the pros: it’s very flexible, and we can create packages without publishing them on a repository like npm.

I think that some sort of package manager will emerge, but nothing official is out yet.

The Deno website provides code hosting (and thus distribution through URLs) to 3rd party packages: https://deno.land/x/

Install Deno

Enough talk! Let’s install Deno.

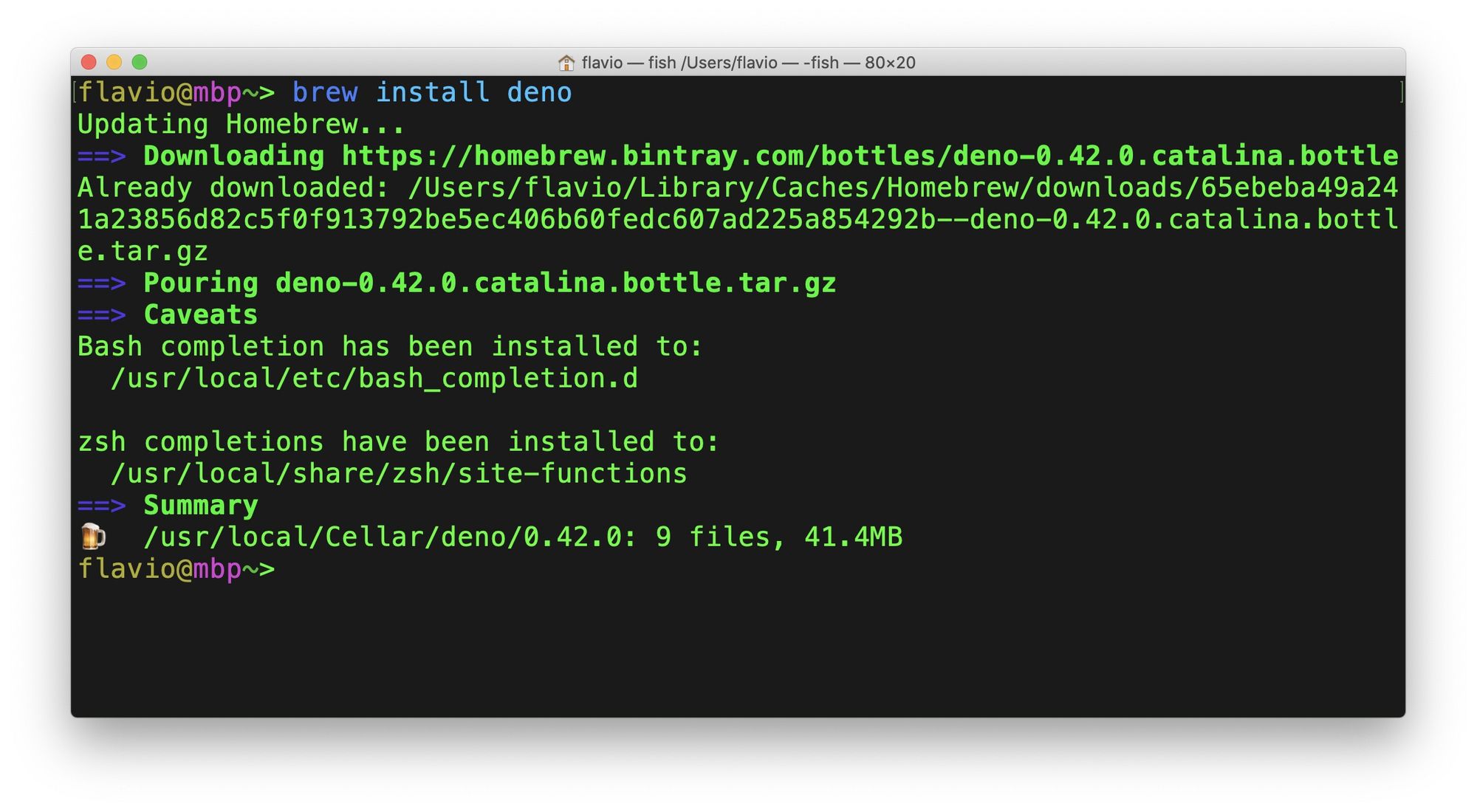

The easiest way is to use Homebrew:

brew install deno

Once this is done, you will have access to the deno command. Here’s the help that you can get using deno --help:

flavio@mbp~> deno --help

deno 0.42.0

A secure JavaScript and TypeScript runtime

Docs: https://deno.land/std/manual.md

Modules: https://deno.land/std/ https://deno.land/x/

Bugs: https://github.com/denoland/deno/issues

To start the REPL, supply no arguments:

deno

To execute a script:

deno run https://deno.land/std/examples/welcome.ts

deno https://deno.land/std/examples/welcome.ts

To evaluate code in the shell:

deno eval "console.log(30933 + 404)"

Run 'deno help run' for 'run'-specific flags.

USAGE:

deno [OPTIONS] [SUBCOMMAND]

OPTIONS:

-h, --help

Prints help information

-L, --log-level <log-level>

Set log level [possible values: debug, info]

-q, --quiet

Suppress diagnostic output

By default, subcommands print human-readable diagnostic messages to stderr.

If the flag is set, restrict these messages to errors.

-V, --version

Prints version information

SUBCOMMANDS:

bundle Bundle module and dependencies into single file

cache Cache the dependencies

completions Generate shell completions

doc Show documentation for a module

eval Eval script

fmt Format source files

help Prints this message or the help of the given subcommand(s)

info Show info about cache or info related to source file

install Install script as an executable

repl Read Eval Print Loop

run Run a program given a filename or url to the module

test Run tests

types Print runtime TypeScript declarations

upgrade Upgrade deno executable to newest version

ENVIRONMENT VARIABLES:

DENO_DIR Set deno's base directory (defaults to $HOME/.deno)

DENO_INSTALL_ROOT Set deno install's output directory

(defaults to $HOME/.deno/bin)

NO_COLOR Set to disable color

HTTP_PROXY Proxy address for HTTP requests

(module downloads, fetch)

HTTPS_PROXY Same but for HTTPSThe Deno commands

Note the SUBCOMMANDS section in the help, that lists all the commands we can run. What subcommands do we have?

bundlebundle module and dependencies of a project into single filecachecache the dependenciescompletionsgenerate shell completionsdocshow documentation for a moduleevalto evaluate a piece of code, e.g.deno eval "console.log(1 + 2)"fmta built-in code formatter (similar togofmtin Go)helpprints this message or the help of the given subcommand(s)infoshow info about cache or info related to source fileinstallinstall script as an executablereplRead-Eval-Print-Loop (the default)runrun a program given a filename or url to the moduletestrun teststypesprint runtime TypeScript declarationsupgradeupgradedenoto the newest version

You can run deno <subcommand> help to get specific additional documentation for the command, for example deno run --help.

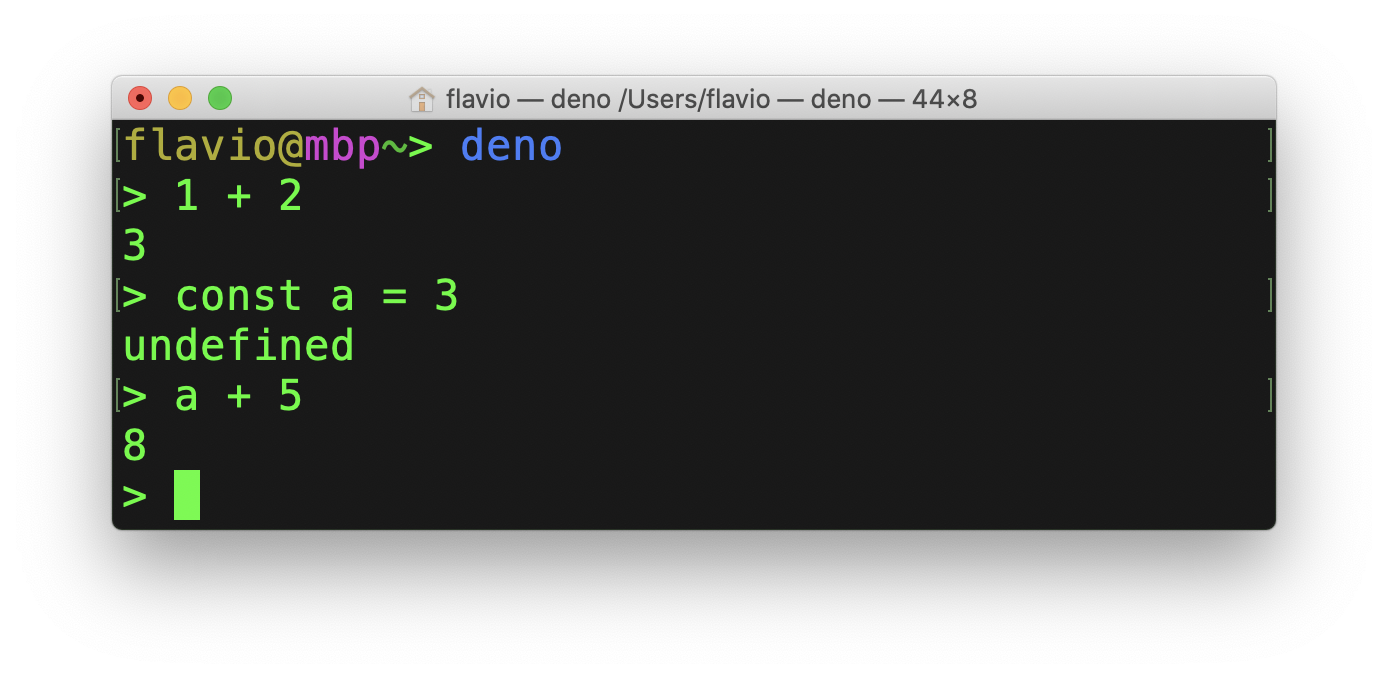

As the help says, we can use this command to start a REPL (Read-Execute-Print-Loop) using deno without any other option.

This is the same as running deno repl.

A more common way you’ll use this command is to execute a Deno app contained in a TypeScript file.

You can run both TypeScript (.ts) files, or JavaScript (.js) files.

If you are unfamiliar with TypeScript, don’t worry: Deno is written in TypeScript, buf you can write your “client” applications in JavaScript.

My TypeScript tutorial will help you get up and running quickly with TypeScript if you want.

Your first Deno app

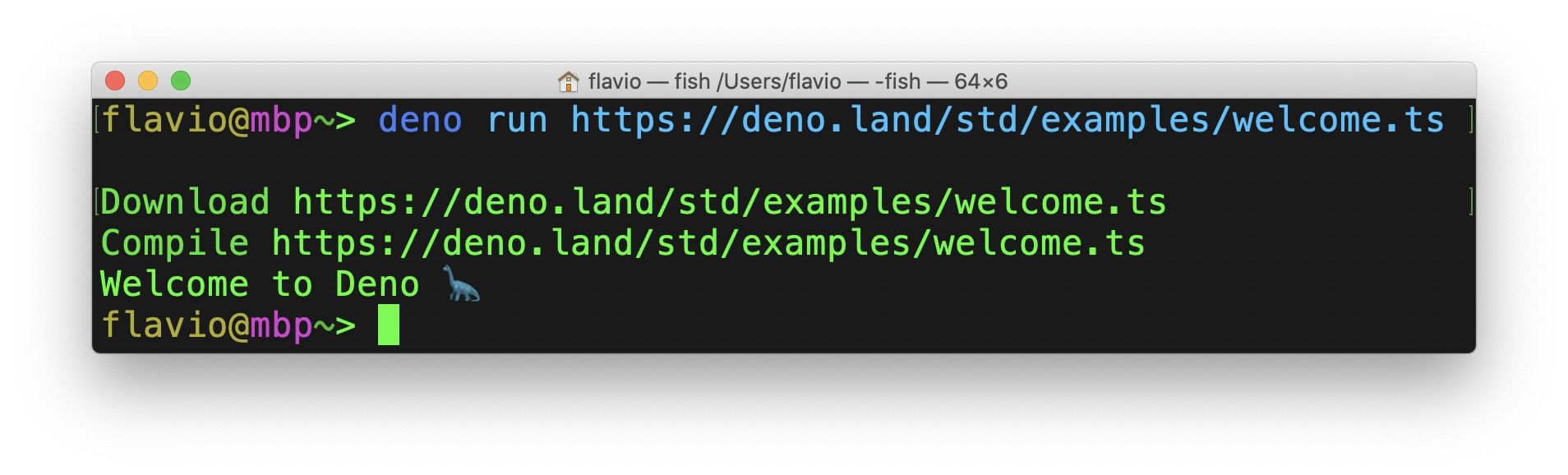

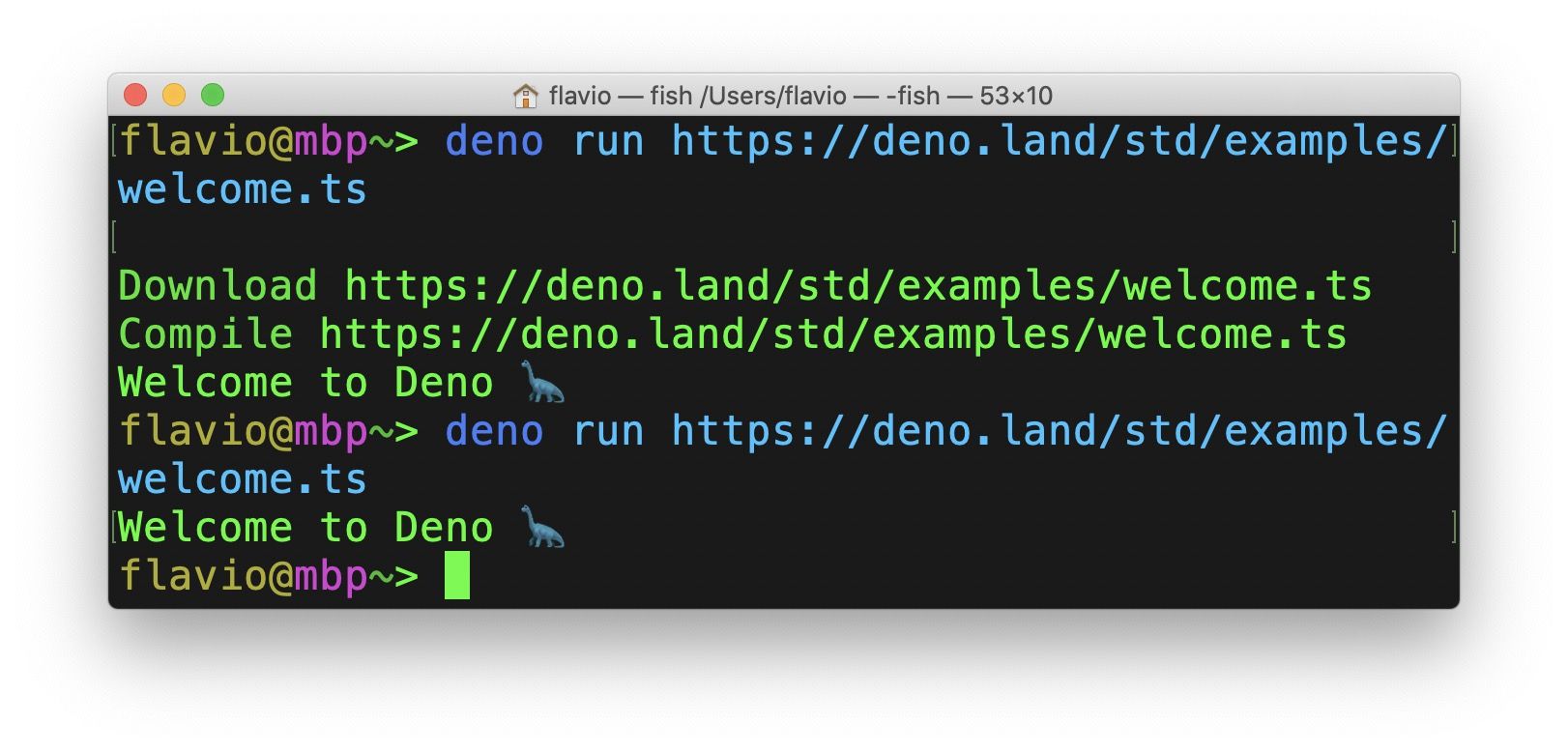

Let’s run a Deno app for the first time.

What I find pretty amazing is that you don’t even have to write a single line – you can run a command from any URL.

Deno downloads the program, compiles it and then runs it:

Of course running arbitrary code from the Internet is not a practice I’d generally recommend. In this case we are running it from the Deno official site, plus Deno has a sandbox that prevents programs to do anything you don’t want to allow. More on this later.

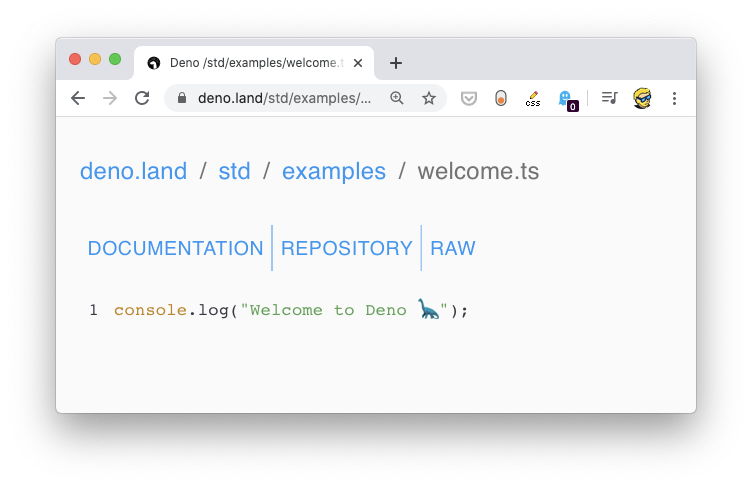

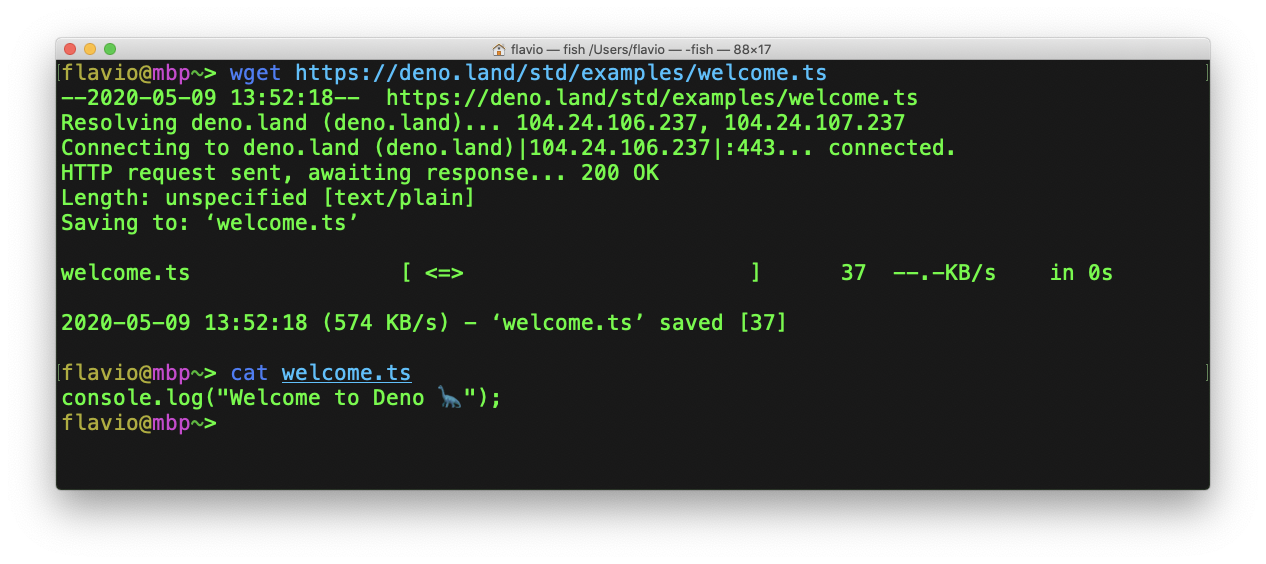

This program is very simple, just a console.log() call:

console.log('Welcome to Deno ?')

If you open the https://deno.land/std/examples/welcome.ts URL with the browser, you’ll see this page:

Weird, right? You’d probably expect a TypeScript file, but instead we have a web page. The reason is the Web server of the Deno website knows you’re using a browser and serves you a more user friendly page.

Download the same UR using wget for example, which requests the text/plain version of it instead of text/html:

If you want to run the program again, it’s now cached by Deno and it does not need to download it again:

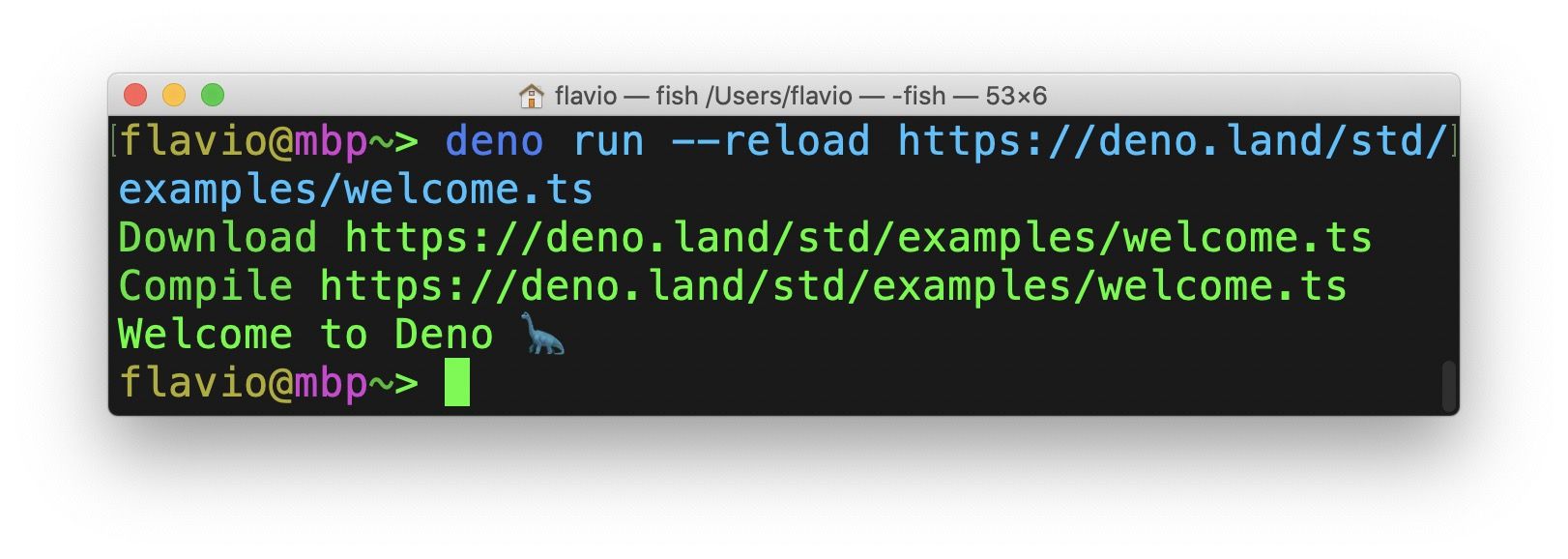

You can force a reload of the original source with the --reload flag:

deno run has lots of different options that were not listed in the deno --help. Instead, you need to run deno run --help to reveal them:

flavio@mbp~> deno run --help

deno-run

Run a program given a filename or url to the module.

By default all programs are run in sandbox without access to disk, network or

ability to spawn subprocesses.

deno run https://deno.land/std/examples/welcome.ts

Grant all permissions:

deno run -A https://deno.land/std/http/file_server.ts

Grant permission to read from disk and listen to network:

deno run --allow-read --allow-net https://deno.land/std/http/file_server.ts

Grant permission to read whitelisted files from disk:

deno run --allow-read=/etc https://deno.land/std/http/file_server.ts

USAGE:

deno run [OPTIONS] <SCRIPT_ARG>...

OPTIONS:

-A, --allow-all

Allow all permissions

--allow-env

Allow environment access

--allow-hrtime

Allow high resolution time measurement

--allow-net=<allow-net>

Allow network access

--allow-plugin

Allow loading plugins

--allow-read=<allow-read>

Allow file system read access

--allow-run

Allow running subprocesses

--allow-write=<allow-write>

Allow file system write access

--cached-only

Require that remote dependencies are already cached

--cert <FILE>

Load certificate authority from PEM encoded file

-c, --config <FILE>

Load tsconfig.json configuration file

-h, --help

Prints help information

--importmap <FILE>

UNSTABLE:

Load import map file

Docs: https://deno.land/std/manual.md#import-maps

Specification: https://wicg.github.io/import-maps/

Examples: https://github.com/WICG/import-maps#the-import-map

--inspect=<HOST:PORT>

activate inspector on host:port (default: 127.0.0.1:9229)

--inspect-brk=<HOST:PORT>

activate inspector on host:port and break at start of user script

--lock <FILE>

Check the specified lock file

--lock-write

Write lock file. Use with --lock.

-L, --log-level <log-level>

Set log level [possible values: debug, info]

--no-remote

Do not resolve remote modules

-q, --quiet

Suppress diagnostic output

By default, subcommands print human-readable diagnostic messages to stderr.

If the flag is set, restrict these messages to errors.

-r, --reload=<CACHE_BLACKLIST>

Reload source code cache (recompile TypeScript)

--reload

Reload everything

--reload=https://deno.land/std

Reload only standard modules

--reload=https://deno.land/std/fs/utils.ts,https://deno.land/std/fmt/colors.ts

Reloads specific modules

--seed <NUMBER>

Seed Math.random()

--unstable

Enable unstable APIs

--v8-flags=<v8-flags>

Set V8 command line options. For help: --v8-flags=--help

ARGS:

<SCRIPT_ARG>...

script argsDeno code examples

In addition to the one we ran above, the Deno website provides some other examples you can check out: https://deno.land/std/examples/.

At the time of writing we can find:

cat.tsprints the content a list of files provided as argumentscatj.tsprints the content a list of files provided as argumentschat/an implementation of a chatcolors.tsan example ofcurl.tsa simple implementation ofcurlthat prints the content of the URL specified as argumentecho_server.tsa TCP echo servergist.tsa program to post files to gist.github.comtest.tsa sample test suitewelcome.tsa simple console.log statement (the first program we ran above)xeval.tsallows you to run any TypeScript code for any line of standard input received. Once known asdeno xevalbut since removed from the official command.

Your first Deno app (for real)

Let’s write some code.

Your first Deno app you ran using deno run https://deno.land/std/examples/welcome.ts was an app that someone else wrote, so you didn’t see anything in regards to how Deno code looks like.

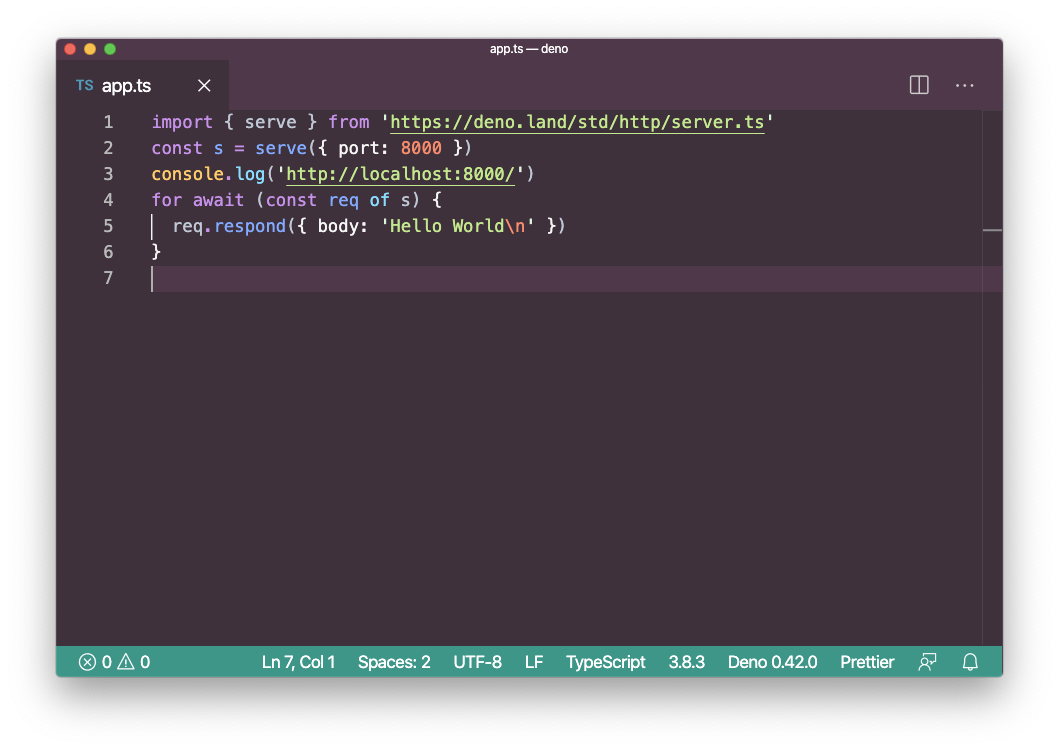

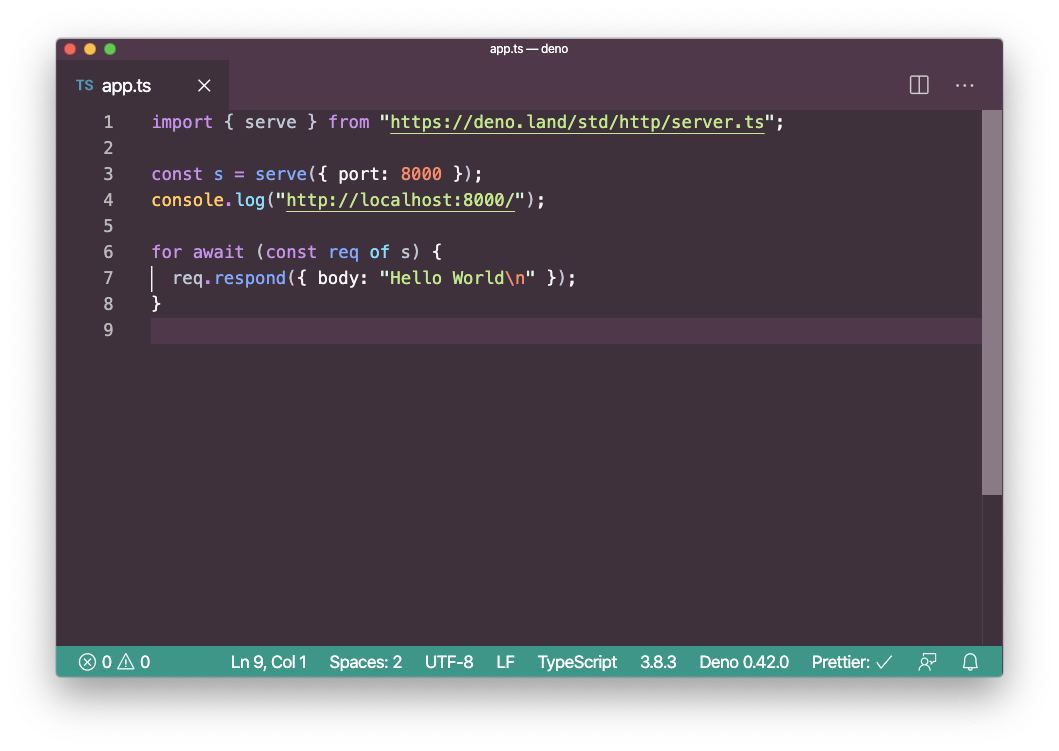

We’ll start from the default example app listed on the Deno official website:

import { serve } from 'https://deno.land/std/http/server.ts'

const s = serve({ port: 8000 })

console.log('http://localhost:8000/')

for await (const req of s) {

req.respond({ body: 'Hello World\n' })

}

This code imports the serve function from the http/server module. See? We don’t have to install it first, and it’s also not stored on your local machine like it happens with Node modules. This is one reason why the Deno installation was so fast.

Importing from https://deno.land/std/http/server.ts imports the latest version of the module. You can import a specific version using @VERSION, like this:

import { serve } from 'https://deno.land/[email protected]/http/server.ts'

The serve function is defined like this in this file:

/**

* Create a HTTP server

*

* import { serve } from "https://deno.land/std/http/server.ts";

* const body = "Hello World\n";

* const s = serve({ port: 8000 });

* for await (const req of s) {

* req.respond({ body });

* }

*/

export function serve(addr: string | HTTPOptions): Server {

if (typeof addr === 'string') {

const [hostname, port] = addr.split(':')

addr = { hostname, port: Number(port) }

}

const listener = listen(addr)

return new Server(listener)

}

We proceed to instantiate a server calling the serve() function passing an object with the port property.

Then we run this loop to respond to every request coming from the server.

for await (const req of s) {

req.respond({ body: 'Hello World\n' })

}

Note that we use the await keyword without having to wrap it into an async function because Deno implements top-level await.

Let’s run this program locally. I assume you use VS Code, but you can use any editor you like.

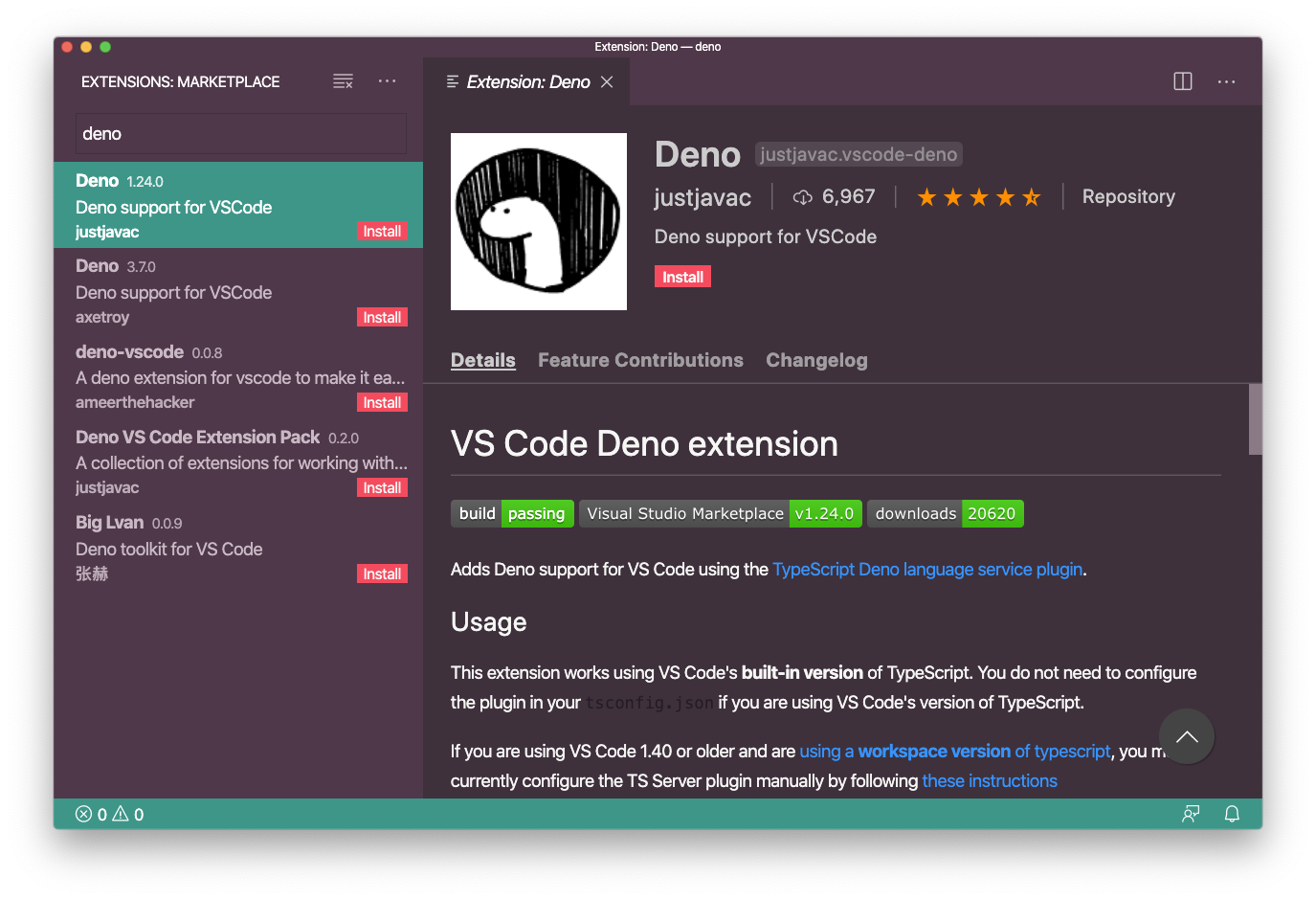

I recommend installing the Deno extension from justjavac (there was another one with the same name when I tried, but deprecated – might disappear in the future)

The extension will provide several utilities and nice thing to VS Code to help you write your apps.

Now create an app.ts file in a folder and paste the above code:

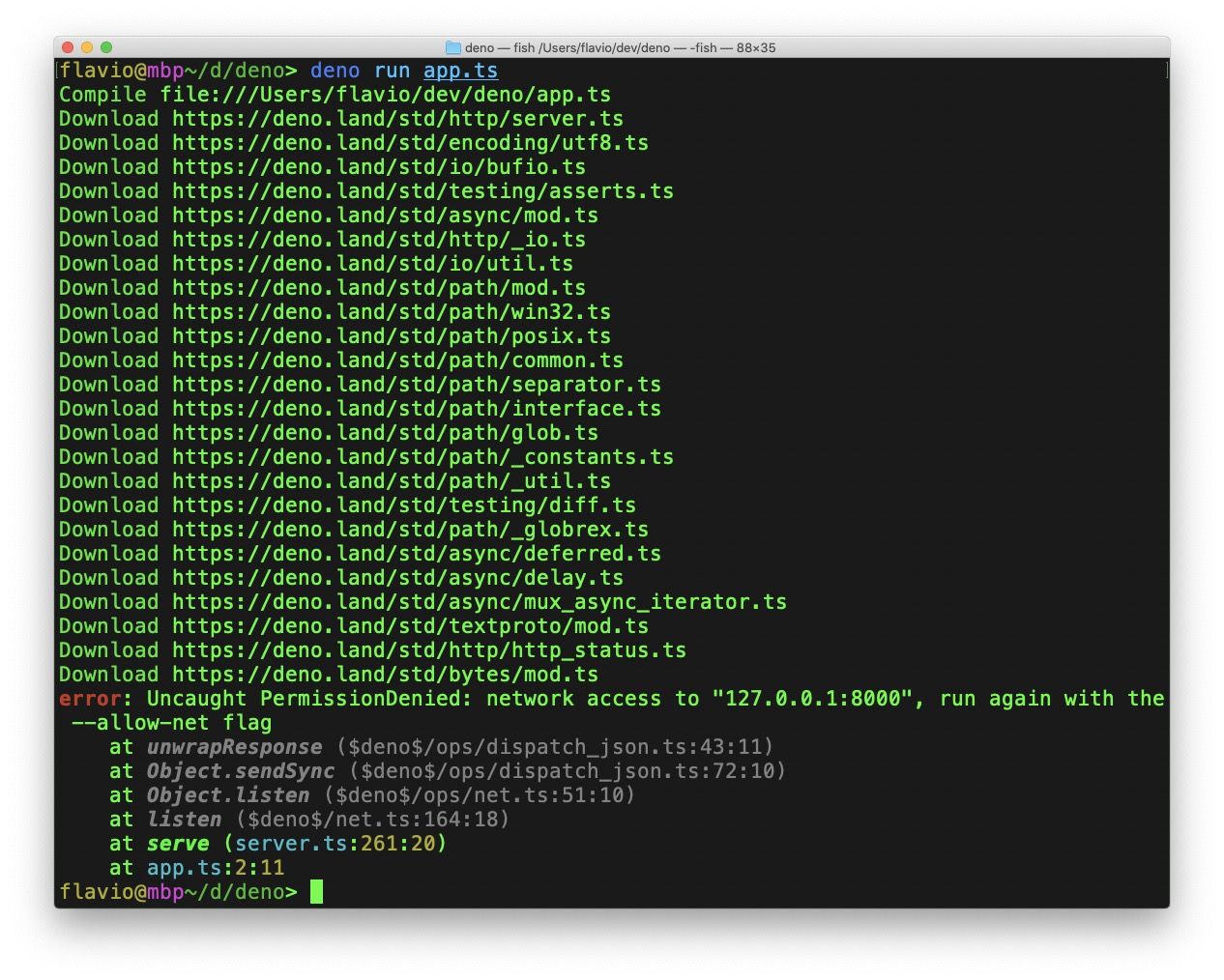

Now run it using deno run app.ts:

Deno downloads all the dependencies it needs, by first downloading the one we imported.

The https://deno.land/std/http/server.ts file has several dependencies on its own:

import { encode } from '../encoding/utf8.ts'

import { BufReader, BufWriter } from '../io/bufio.ts'

import { assert } from '../testing/asserts.ts'

import { deferred, Deferred, MuxAsyncIterator } from '../async/mod.ts'

import {

bodyReader,

chunkedBodyReader,

emptyReader,

writeResponse,

readRequest,

} from './_io.ts'

import Listener = Deno.Listener

import Conn = Deno.Conn

import Reader = Deno.Reader

and those are imported automatically.

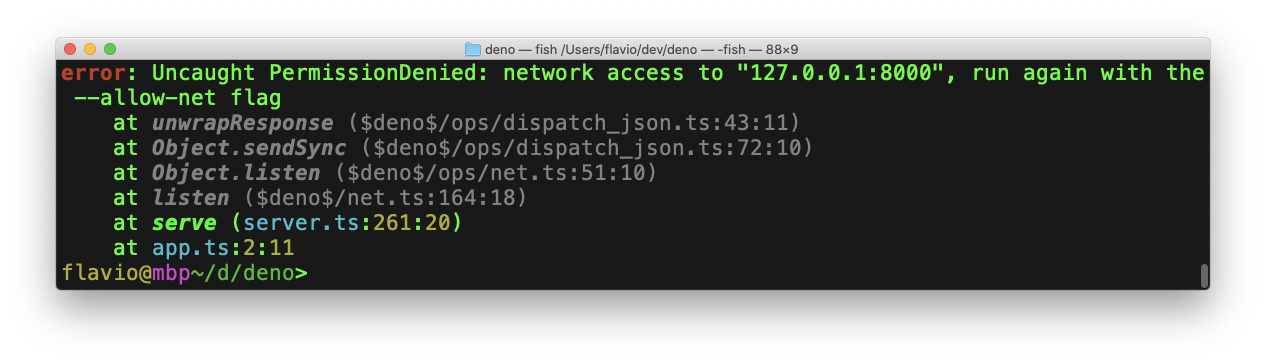

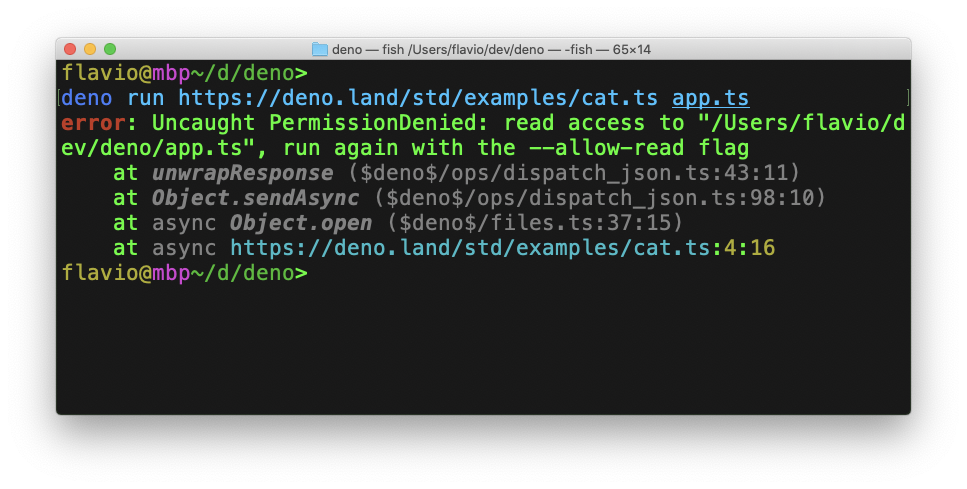

At the end though we have a problem:

What is happening? We have a permission denied problem.

Let’s talk about the sandbox.

The Deno sandbox

I mentioned previously that Deno has a sandbox that prevents programs from doing anything you don’t want to allow.

What does this mean?

One of the things that Ryan mentions in the Deno introduction talk is that sometimes you want to run a JavaScript program outside of the Web Browser, and yet do not want allow it to access to anything it wants on your system. Or talk to the external world using a network.

There’s nothing stopping a Node.js app from getting your SSH keys or any other thing on your system and sending it to a server. This is why we usually only install Node packages from trusted sources. But how can we know if one of the projects we use gets hacked and in turn everyone else does?

Deno tries to replicate the same permission model that the browser implements. No JavaScript running in the browser can do shady things on your system unless you explicitly allow it.

Going back to Deno, if a program want to access the network like in the previous case, then we need to give it permission.

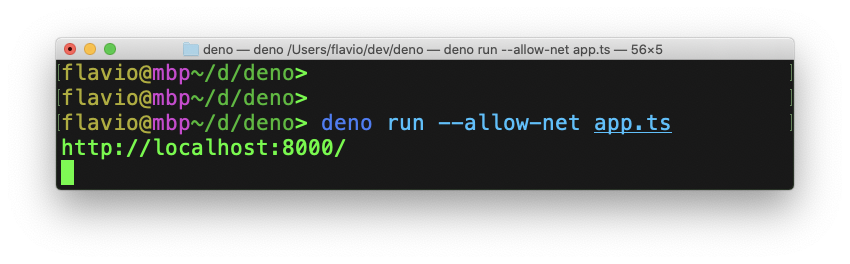

We can do so by passing a flag when we run the command, in this case --allow-net:

deno run --allow-net app.ts

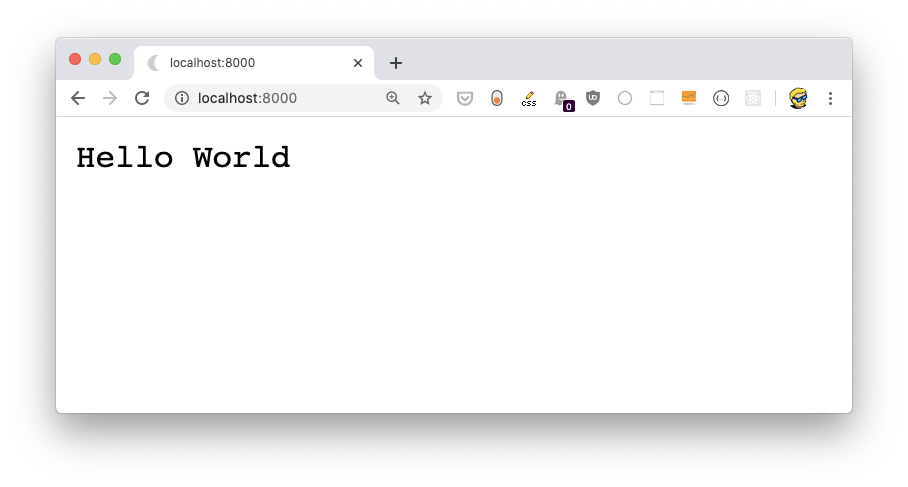

The app is now running an HTTP server on port 8000:

Other flags allow Deno to unlock other functionality:

--allow-envallow environment access--allow-hrtimeallow high resolution time measurement--allow-net=<allow-net>allow network access--allow-pluginallow loading plugins--allow-read=<allow-read>allow file system read access--allow-runallow running subprocesses--allow-write=<allow-write>allow file system write access--allow-allallow all permissions (same as-A)

Permissions for net, read and write can be granular. For example, you can allow reading from a specific folder using --allow-read=/dev

Formatting code

One of the things I really liked from Go was the gofmt command that came with the Go compiler. All Go code looks the same. Everyone uses gofmt.

JavaScript programmers are used to running Prettier, and deno fmt actually runs that under the hood.

Say you have a file formatted badly like this:

You run deno fmt app.ts and it’s automatically formatted properly, also adding semicolons where missing:

The standard library

The Deno standard library is extensive despite the project being very young.

It includes:

archivetar archive utilitiesasyncasync utiltiesbyteshelpers to manipulate bytes slicesdatetimedate/time parsingencodingencoding/decoding for various formatsflagsparse command-line flagsfmtformatting and printingfsfile system APIhashcrypto libhttpHTTP serverioI/O libloglogging utilitiesmimesupport for multipart datanodeNode.js compatibility layerpathpath manipulationwswebsockets

Another Deno example

Let’s see another example of a Deno app, from the Deno examples: cat:

const filenames = Deno.args

for (const filename of filenames) {

const file = await Deno.open(filename)

await Deno.copy(file, Deno.stdout)

file.close()

}

This assigns to the filenames variable the content of Deno.args, which is a variable containing all the arguments sent to the command.

We iterate through them, and for each we use Deno.open() to open the file and we use Deno.copy() to print the content of the file to Deno.stdout. Finally we close the file.

If you run this using

deno run https://deno.land/std/examples/cat.tsThe program is downloaded and compiled, and nothing happens because we didn’t specify any argument.

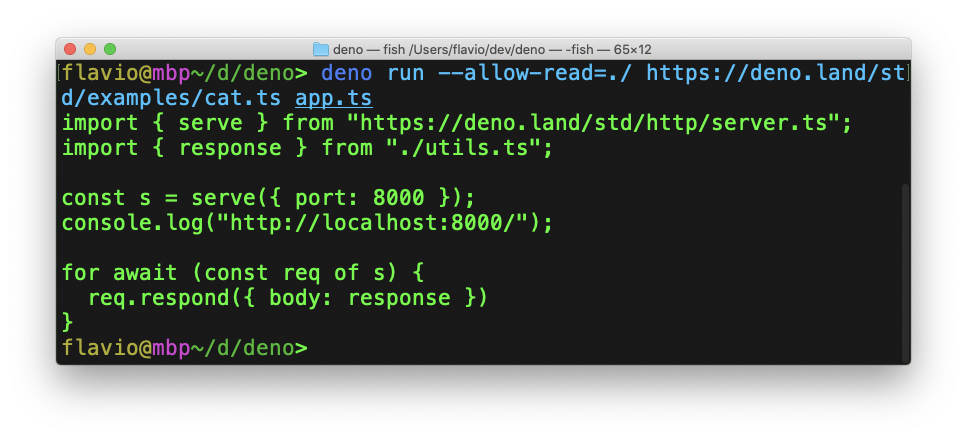

Try now

deno run https://deno.land/std/examples/cat.ts app.tsassuming you have app.ts from the previous project in the same folder.

You’ll get a permission error:

Because Deno disallows access to the filesystem by default. Grant access to the current folder using --allow-read=./:

deno run --allow-read=./ https://deno.land/std/examples/cat.ts app.ts

Is there an Express/Hapi/Koa/* for Deno?

Yes, definitely. Check out projects like

Example: use Oak to build a REST API

I want to make a simple example of how to build a REST API using Oak. Oak is interesting because it’s inspired by Koa, the popular Node.js middleware, and due to this it’s very familiar if you’ve used that before.

The API we’re going to build is very simple.

Our server will store, in memory, a list of dogs with name and age.

We want to:

- add new dogs

- list dogs

- get details about a specific dog

- remove a dog from the list

- update a dog’s age

We’ll do this in TypeScript, but nothing stops you from writing the API in JavaScript – you simply remove the types.

Create a app.ts file.

Let’s start by importing the Application and Router objects from Oak:

import { Application, Router } from 'https://deno.land/x/oak/mod.ts'

then we get the environment variables PORT and HOST:

const env = Deno.env.toObject()

const PORT = env.PORT || 4000

const HOST = env.HOST || '127.0.0.1'

By default our app will run on localhost:4000.

Now we create the Oak application and we start it:

const router = new Router()

const app = new Application()

app.use(router.routes())

app.use(router.allowedMethods())

console.log(`Listening on port ${PORT}...`)

await app.listen(`${HOST}:${PORT}`)

Now the app should be compiling fine.

Run

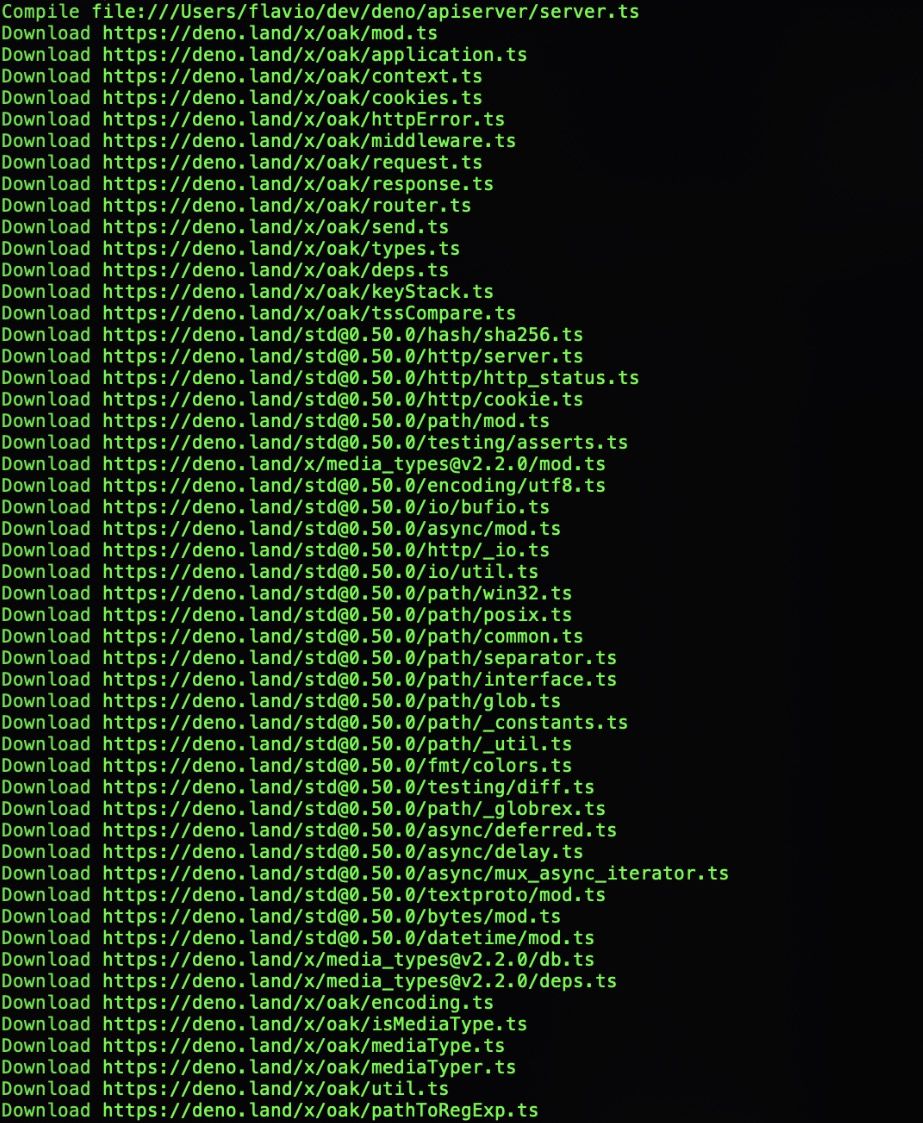

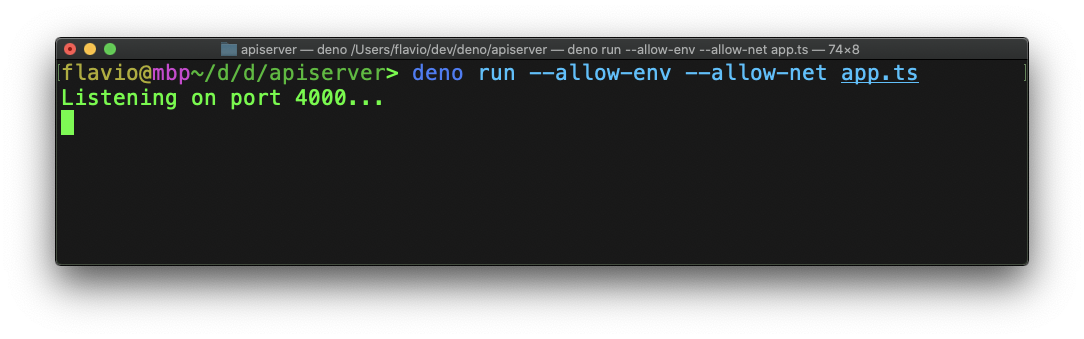

deno run --allow-env --allow-net app.tsand Deno will download the dependencies:

and then listen on port 4000.

The next times you run the command, Deno will skip the installation part because those packages are already cached:

At the top of the file, let’s define an interface for a dog, then we declare an initial dogs array of Dog objects:

interface Dog {

name: string

age: number

}

let dogs: Array<Dog> = [

{

name: 'Roger',

age: 8,

},

{

name: 'Syd',

age: 7,

},

]

Now let’s actually implement the API.

We have everything in place. After you create the router, let’s add some functions that will be invoked any time one of those endpoints is hit:

const router = new Router()

router

.get('/dogs', getDogs)

.get('/dogs/:name', getDog)

.post('/dogs', addDog)

.put('/dogs/:name', updateDog)

.delete('/dogs/:name', removeDog)

See? We define

GET /dogsGET /dogs/:namePOST /dogsPUT /dogs/:nameDELETE /dogs/:name

Let’s implement those one-by-one.

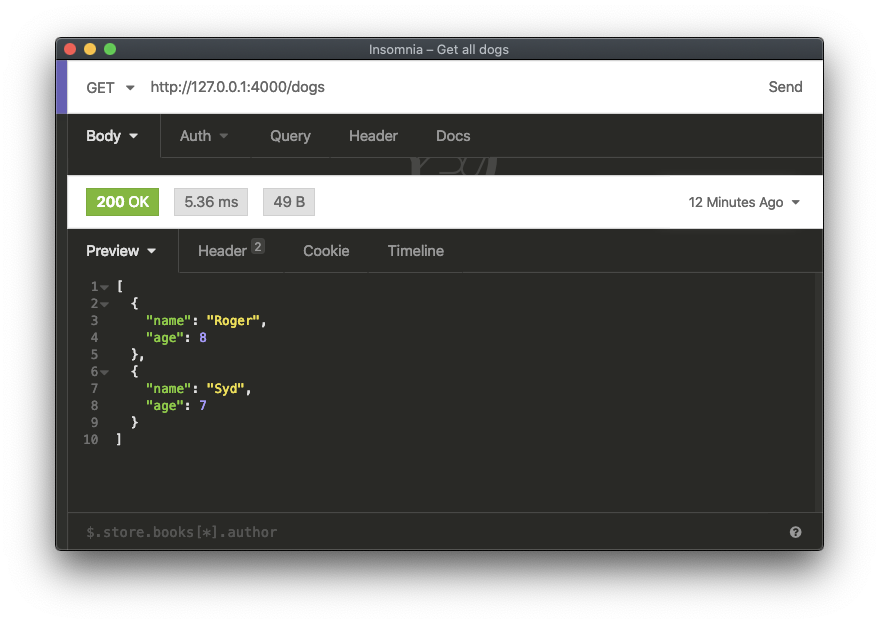

Starting from GET /dogs, which returns the list of all the dogs:

export const getDogs = ({ response }: { response: any }) => {

response.body = dogs

}

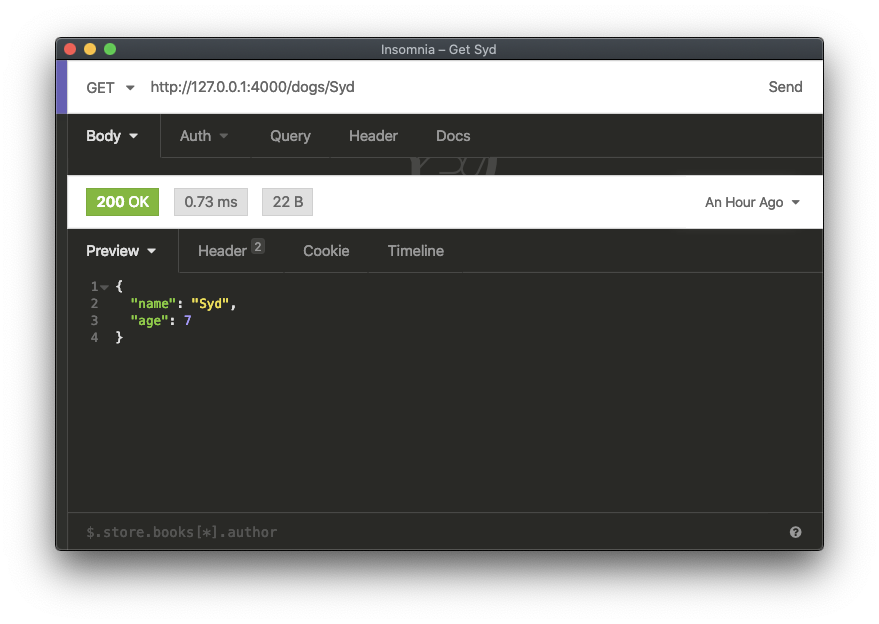

Next, here’s how we can retrieve a single dog by name:

export const getDog = ({

params,

response,

}: {

params: {

name: string

}

response: any

}) => {

const dog = dogs.filter((dog) => dog.name === params.name)

if (dog.length) {

response.status = 200

response.body = dog[0]

return

}

response.status = 400

response.body = { msg: `Cannot find dog ${params.name}` }

}

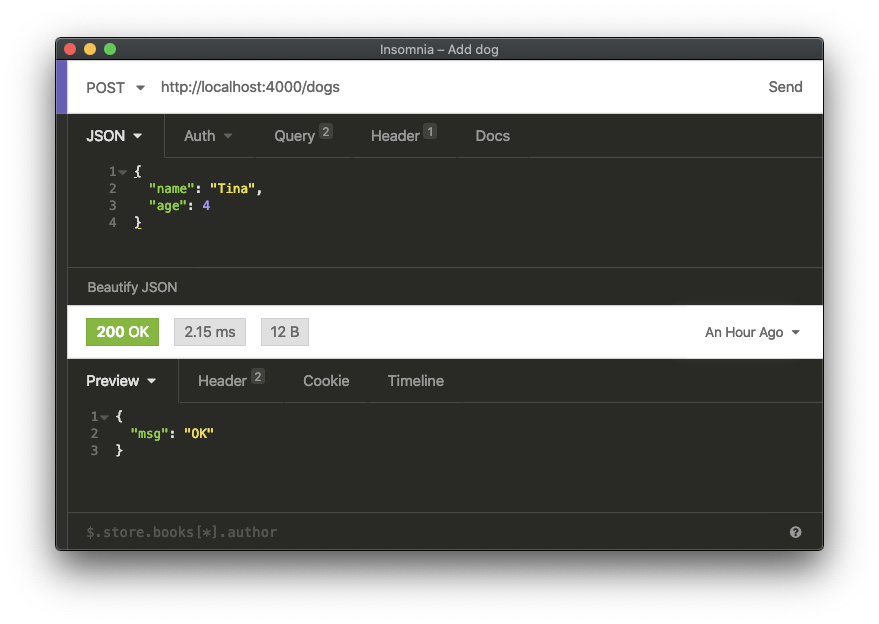

Here is how we add a new dog:

export const addDog = async ({

request,

response,

}: {

request: any

response: any

}) => {

const body = await request.body()

const dog: Dog = body.value

dogs.push(dog)

response.body = { msg: 'OK' }

response.status = 200

}

Notice that I now used const body = await request.body() to get the content of the body, since the name and age values are passed as JSON.

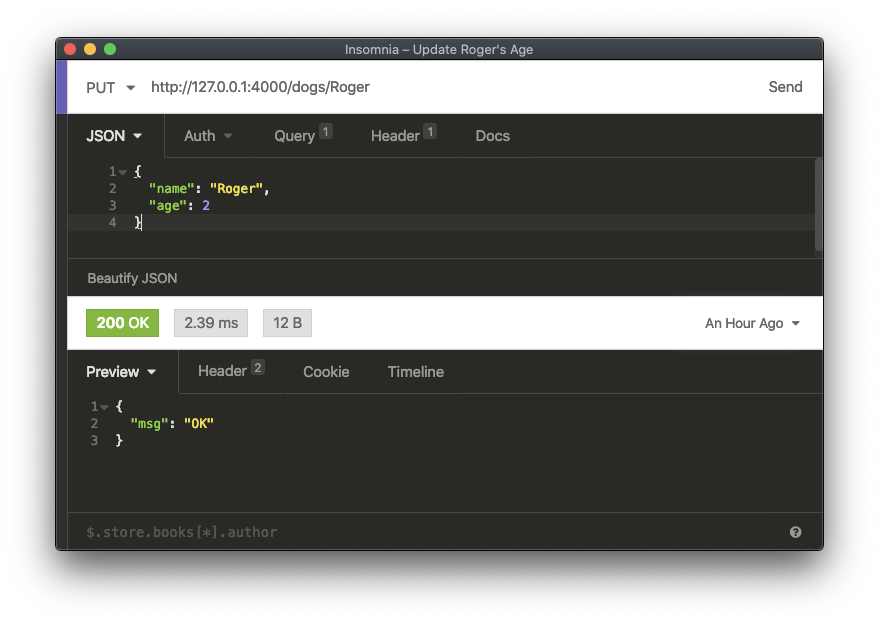

Here’s how we update a dog’s age:

export const updateDog = async ({

params,

request,

response,

}: {

params: {

name: string

}

request: any

response: any

}) => {

const temp = dogs.filter((existingDog) => existingDog.name === params.name)

const body = await request.body()

const { age }: { age: number } = body.value

if (temp.length) {

temp[0].age = age

response.status = 200

response.body = { msg: 'OK' }

return

}

response.status = 400

response.body = { msg: `Cannot find dog ${params.name}` }

}

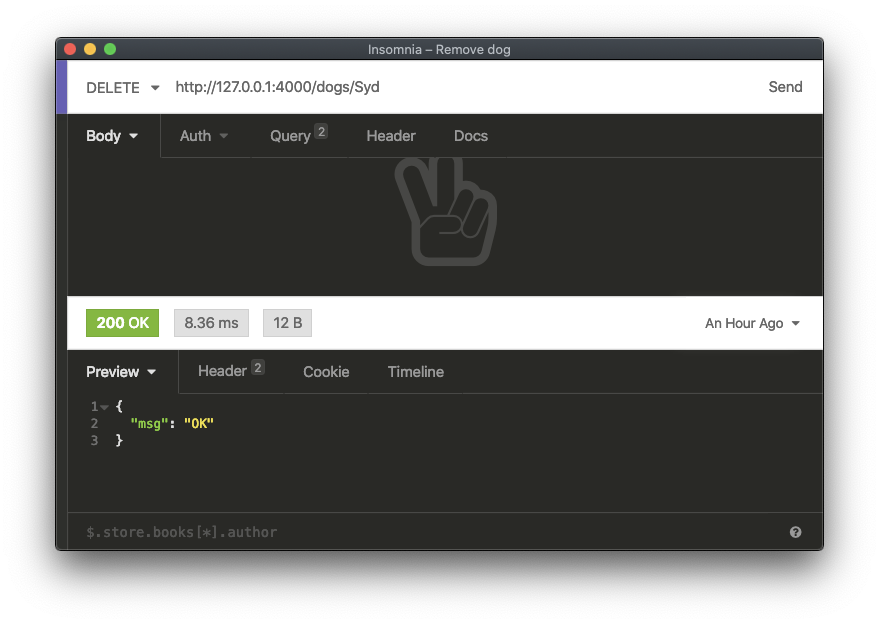

and here is how we can remove a dog from our list:

export const removeDog = ({

params,

response,

}: {

params: {

name: string

}

response: any

}) => {

const lengthBefore = dogs.length

dogs = dogs.filter((dog) => dog.name !== params.name)

if (dogs.length === lengthBefore) {

response.status = 400

response.body = { msg: `Cannot find dog ${params.name}` }

return

}

response.body = { msg: 'OK' }

response.status = 200

}

Here’s the complete example code:

import { Application, Router } from 'https://deno.land/x/oak/mod.ts'

const env = Deno.env.toObject()

const PORT = env.PORT || 4000

const HOST = env.HOST || '127.0.0.1'

interface Dog {

name: string

age: number

}

let dogs: Array<Dog> = [

{

name: 'Roger',

age: 8,

},

{

name: 'Syd',

age: 7,

},

]

export const getDogs = ({ response }: { response: any }) => {

response.body = dogs

}

export const getDog = ({

params,

response,

}: {

params: {

name: string

}

response: any

}) => {

const dog = dogs.filter((dog) => dog.name === params.name)

if (dog.length) {

response.status = 200

response.body = dog[0]

return

}

response.status = 400

response.body = { msg: `Cannot find dog ${params.name}` }

}

export const addDog = async ({

request,

response,

}: {

request: any

response: any

}) => {

const body = await request.body()

const { name, age }: { name: string; age: number } = body.value

dogs.push({

name: name,

age: age,

})

response.body = { msg: 'OK' }

response.status = 200

}

export const updateDog = async ({

params,

request,

response,

}: {

params: {

name: string

}

request: any

response: any

}) => {

const temp = dogs.filter((existingDog) => existingDog.name === params.name)

const body = await request.body()

const { age }: { age: number } = body.value

if (temp.length) {

temp[0].age = age

response.status = 200

response.body = { msg: 'OK' }

return

}

response.status = 400

response.body = { msg: `Cannot find dog ${params.name}` }

}

export const removeDog = ({

params,

response,

}: {

params: {

name: string

}

response: any

}) => {

const lengthBefore = dogs.length

dogs = dogs.filter((dog) => dog.name !== params.name)

if (dogs.length === lengthBefore) {

response.status = 400

response.body = { msg: `Cannot find dog ${params.name}` }

return

}

response.body = { msg: 'OK' }

response.status = 200

}

const router = new Router()

router

.get('/dogs', getDogs)

.get('/dogs/:name', getDog)

.post('/dogs', addDog)

.put('/dogs/:name', updateDog)

.delete('/dogs/:name', removeDog)

const app = new Application()

app.use(router.routes())

app.use(router.allowedMethods())

console.log(`Listening on port ${PORT}...`)

await app.listen(`${HOST}:${PORT}`)

Find out more

The Deno official website is https://deno.land

The API documentation is available at https://doc.deno.land and https://deno.land/typedoc/index.html

awesome-deno https://github.com/denolib/awesome-deno

A few more random tidbits

- Deno provides a built-in

fetchimplementation that matches the one available in the browser - Deno has a compatibility layer with the Node.js stdlib in progress

Final words

I hope you enjoyed this Deno tutorial!

Reminder: You can get a PDF/ePub/Mobi version of this Deno Handbook here.