The Amazon Dash Button: A Retrospective

The Internet of Things will revolutionize everything! Manufacturing? Dog walking? Coffee bean refilling? Car driving? Food eating? Put a sensor in it! The marketing makes it pretty clear that there’s no part of our lives which isn’t enhanced with The Internet of Things. Why? Because with a simple sensor and a symphony of corporate hand waving about machine learning an iPhone-style revolution is just around the corner! Enter: Amazon Dash, circa 2014.

The first product in the Dash family was actually a barcode scanning wand which was freely given to Amazon Fresh customers and designed to hang in the kitchen or magnet to the fridge. When the Fresh customer ran out of milk they could scan the carton as it was being thrown away to add it to their cart for reorder. I suspect these devices were fairly expensive, and somewhat too complex to be as frequently used as Amazon wanted (thus the extremely limited launch). Amazon’s goal here was to allow potential customers to order with an absolute minimum of friction so they can buy as much as possible. Remember the “Buy now with 1-Click” button?

That original Dash Wand was eventually upgraded to include a push button activated Alexa (barcode scanner and fridge magnet intact) and is generally available. But Amazon had pinned its hopes on a new beau. Mid 2015 Amazon introduced the Dash Replenishment Service along with a product to be it’s exemplar – the Dash Button. The Dash Button was to be the 1-Click button of the physical world. The barcode-scanning Wands require the user to remember the Wand was nearby, find a barcode, scan it, then remember to go to their cart and order the product. Too many steps, too many places to get off Mr. Bezos’ Wild Ride of Commerce. The Dash Buttons were simple! Press the button, get the labeled product shipped to a preconfigured address. Each button was purchased (for $5, with a $5 coupon) with a particular brand affinity, then configured online to purchase a specific product when pressed. In the marketing materials, happy families put them on washing machines to buy Tide, or in a kitchen cabinet to buy paper towels. Pretty clever, it really is a Buy now with 1-Click button for the physical world.

There were two versions of the Dash button. Both have the same user interface and work in fundamentally the same way. They have a single button (the software can recognize a few click patterns), a single RGB LED (‘natch), and a microphone (no, it didn’t listen to you, but we’ll come back to this). They also had a WiFi radio. Version two (silently released in 2016) added Bluetooth and completely changed the electrical innards, though to no user facing effect.

In February 2019, Amazon stopped selling the Dash Buttons.

This is Hackaday, not Business Insider

Right, why are we eulogizing a corporate strategy on Hackaday? The Dash Buttons were a clever hack! In a post-ESP8266 world, hardware like the Dash Button is the standard home automation starter project. But in 2015 when the Buttons were released the ESP was just starting to make waves. Up until that point, WiFi meant an unusual device like an Electric Imp or expensive ICs with an image of Texas on them. The market for low cost internet connected devices was very different, and much more expensive, back then.

A device like the Dash button probably doesn’t make sense for Amazon to build if it costs more than a couple dollars to make, so a few tricks were played to keep costs down without compromising user experience.

The clever hacks start with the pairing experience. Classical methods for attaching purely WiFi devices to a home network are typically a disaster of a user experience. Boot the device for the first time, wait for it to figure out it has no network connection and go into access point mode, open an app, manually open a settings page and connect to the new WiFi network, go back to the app, enter credentials, wait an interminable time for something to tell you it succeeded. And that only works if your phone doesn’t kill the app in the background or drop off the WiFi network because it doesn’t have an internet connection! At various points on Android the app developer may have been able to force a WiFi network switch without user intervention, but even in that case the experience between platforms is seriously inconsistent.

The clever hacks start with the pairing experience. Classical methods for attaching purely WiFi devices to a home network are typically a disaster of a user experience. Boot the device for the first time, wait for it to figure out it has no network connection and go into access point mode, open an app, manually open a settings page and connect to the new WiFi network, go back to the app, enter credentials, wait an interminable time for something to tell you it succeeded. And that only works if your phone doesn’t kill the app in the background or drop off the WiFi network because it doesn’t have an internet connection! At various points on Android the app developer may have been able to force a WiFi network switch without user intervention, but even in that case the experience between platforms is seriously inconsistent.

So what’s a hacker to do? Bluetooth works pretty well, but requires another radio. The previously mentioned Electric Imp uses a photosensor that you press against your phone screen while it spastically flashes in a pattern encoding the credentials. Devices could be preprogrammed, like Amazon does with a new Kindle and the purchaser’s Amazon account credentials, but this is an elaborate factory process and you still need a fallback for when networks change. Instead of these workarounds, Amazon chose something I’ve only ever heard as a joke; acoustic pairing.

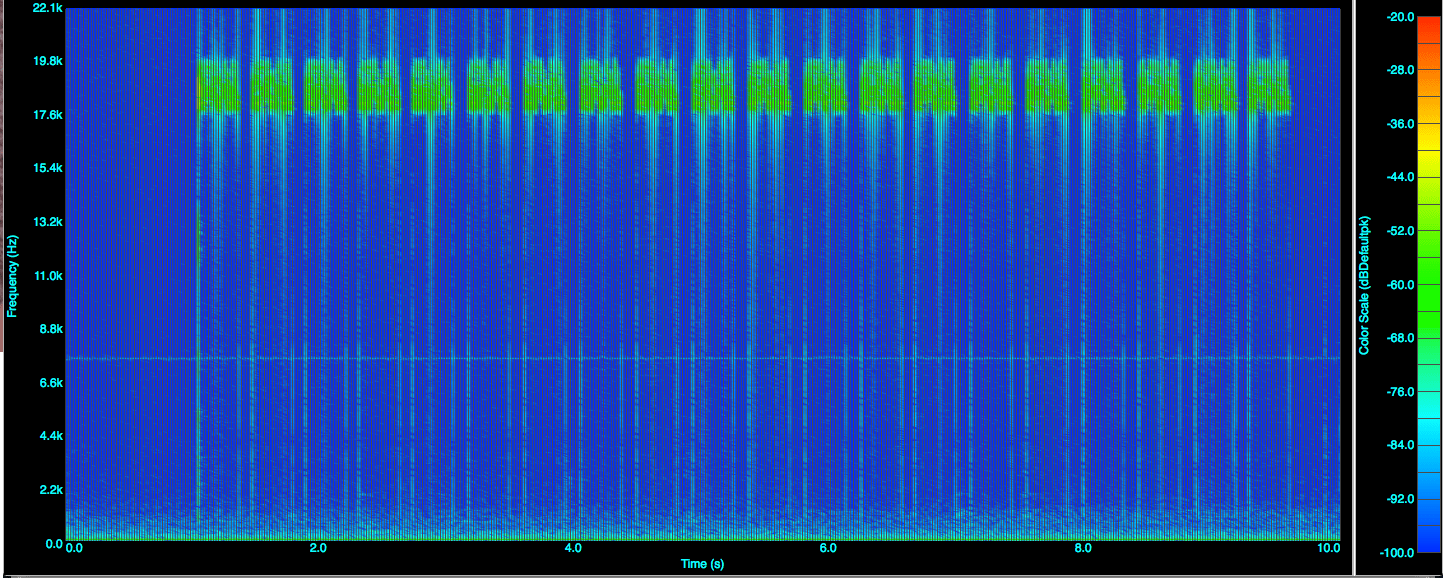

Both generations of Dash button include a single microphone which receives the user’s network credentials via frequency shift keyed acoustic tones a hair below 20 kHz. Why 20 kHz and not above? The acoustic pairing method is designed to work anywhere there is a mic and a speaker. These requirements are so easily satisfied that Amazon could write the pairing flow to work on more than just a native app, allowing people to use anything from a Chromebook with a desktop browser to another Amazon device to go through the flow. I’m not aware of them doing silent setup from a nearby Echo, but it would have been technically feasible and absolutely magical. With that scope in mind it needs to be in a frequency range that would always be reproduced accurately, which means the human auditory range. For more detail check out [Jay]’s awesome reverse engineering of the protocol (33C3 talk here).

Both generations of Dash button include a single microphone which receives the user’s network credentials via frequency shift keyed acoustic tones a hair below 20 kHz. Why 20 kHz and not above? The acoustic pairing method is designed to work anywhere there is a mic and a speaker. These requirements are so easily satisfied that Amazon could write the pairing flow to work on more than just a native app, allowing people to use anything from a Chromebook with a desktop browser to another Amazon device to go through the flow. I’m not aware of them doing silent setup from a nearby Echo, but it would have been technically feasible and absolutely magical. With that scope in mind it needs to be in a frequency range that would always be reproduced accurately, which means the human auditory range. For more detail check out [Jay]’s awesome reverse engineering of the protocol (33C3 talk here).

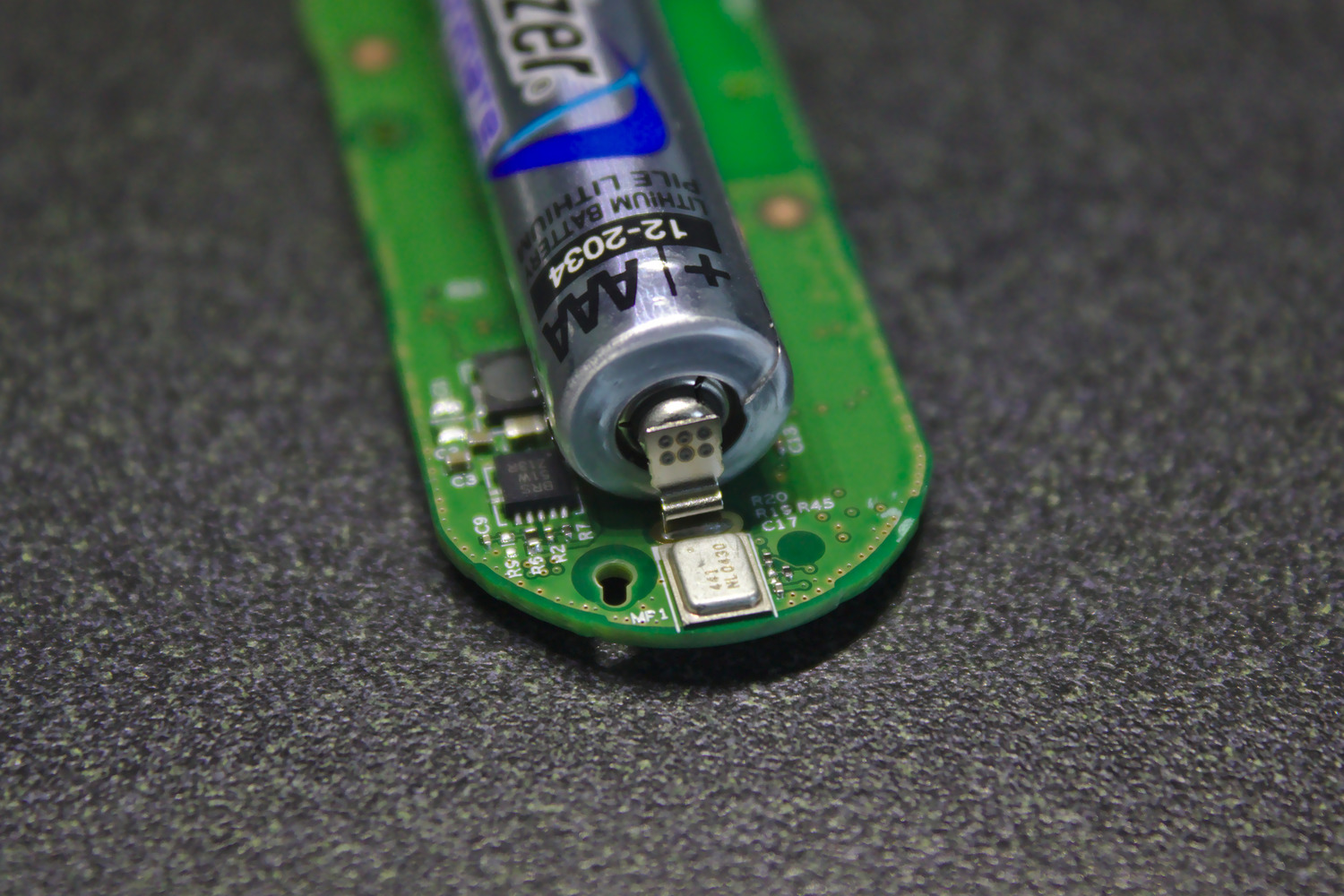

Moving into the device we are faced with an unusual sight; a AA battery! And not a rebranded “industrial” battery, a real consumer one with the branding intact, spot welded to its contacts. Huh? Well, apparently Amazon decided that a common coin cell wouldn’t afford a long enough service life, perhaps due to energy consumption during WiFi rejoin on wake, and a larger coin cell was probably significantly more expensive than a normal consumer battery. Though the battery is well captured by a plastic midframe (black oval, left) it’s unfortunately welded to the tabs, meaning the entire assembly would need to be replaced when the battery runs out after a thousand or so presses. We’d love to see someone find some compatible battery tabs on Digikey and start printing replacement cases!

Moving into the device we are faced with an unusual sight; a AA battery! And not a rebranded “industrial” battery, a real consumer one with the branding intact, spot welded to its contacts. Huh? Well, apparently Amazon decided that a common coin cell wouldn’t afford a long enough service life, perhaps due to energy consumption during WiFi rejoin on wake, and a larger coin cell was probably significantly more expensive than a normal consumer battery. Though the battery is well captured by a plastic midframe (black oval, left) it’s unfortunately welded to the tabs, meaning the entire assembly would need to be replaced when the battery runs out after a thousand or so presses. We’d love to see someone find some compatible battery tabs on Digikey and start printing replacement cases!

What about the rest of the enclosure? It looks just about as simple as can be. There are screws to hold the PCBA to the top of the case, but everything else is glued or ultrasonically welded together. The shape of each plastic components also seems to be quite friendly for injection molding, with no overhangs and a curved geometry very amenable to hefty draft angles. All in all the device appears to be fast and easy (read: cheap) to manufacture, which isn’t a huge surprise.

Hackability

What hacks can you perform on a Dash Button? If people are going to begin throwing away these astonishingly cheap devices, can we give them another life?

Perhaps the first Dash hacks repurposed the devices without software or hardware hackery at all. When a Button is between presses, it is turned off to save power. Long term, even the occasional spikes to keep up with WiFi connection intervals would represent significant power consumption: the Dash Buttons are designed to last for years of normal usage, so they don’t stay connected. When you press the button, the device wakes up, toggles its LED to indicate liveliness, connects to WiFi, hits Amazon’s API, then drops back off the network and turns the lights out. When they connect to your local network they necessarily go through a few setup steps including broadcasting an ARP probe to make sure no one else is sharing the same MAC address.

Enterprising hackers realized that if you can watch traffic on your LAN then you can see these ARP probes, which include the device’s unique MAC address. And because of the very specific lifecycle of a Dash Button, if you can see the ARP probe then you can imply the device just woke up, which in turn means the button was just pressed. At that point doing something with that information is just plumbing. The first mention of this method that I’ve found is from [Ted] in this post. Even if Amazon’s back end eventually goes down there’s no reason this would stop working.

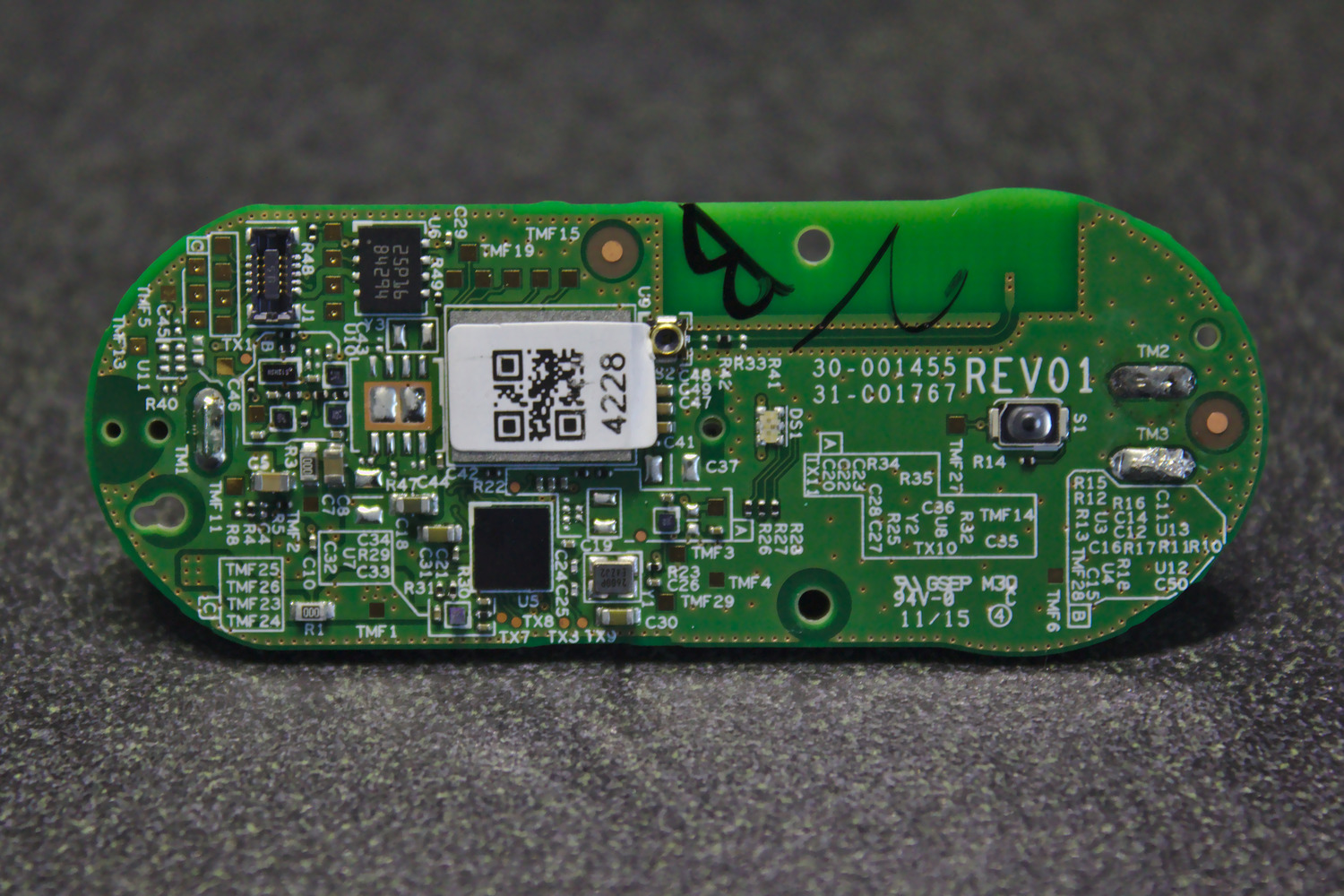

Catching ARP probes works, but feels pretty rickety to me. These things have processors already so we should be able to make them do the talking themselves. What about programming the Dash Button? Unsurprisingly people have mapped out the board and established which test points go where. Neither version has particularly unusual parts: version 1 has a Broadcom Cypress BCM943362WCD4 module from the WICED family which is just an STM32F205 glued to a radio, for which a devkit is available. Version 2 seems to be an Atmel Microchip ATSAMG55 and an Atmel Microchip ATWINC1500B, with a Cypress CYBL10563-68FNXI Bluetooth radio for good measure. Interesting commentary about market consolidation aside, these are well documented ARM CPUs which are freely available.

Catching ARP probes works, but feels pretty rickety to me. These things have processors already so we should be able to make them do the talking themselves. What about programming the Dash Button? Unsurprisingly people have mapped out the board and established which test points go where. Neither version has particularly unusual parts: version 1 has a Broadcom Cypress BCM943362WCD4 module from the WICED family which is just an STM32F205 glued to a radio, for which a devkit is available. Version 2 seems to be an Atmel Microchip ATSAMG55 and an Atmel Microchip ATWINC1500B, with a Cypress CYBL10563-68FNXI Bluetooth radio for good measure. Interesting commentary about market consolidation aside, these are well documented ARM CPUs which are freely available.

And yet, despite availability of both demonstration hardware and Dash Buttons, no one seems to have gotten very far. It’s easy to find great tutorials on reflashing the device and blinking the LED or listening for button presses, but every tutorial I’ve found ends with the frustrating cliffhanger “from here, just figure out WiFi.” So yes they can be reprogrammed into weird little development boards, but we have yet to see someone fully control the device so we can access all the juicy functionality contained within.

What’s Next?

Before wrapping up, lets take a moment to alternatively commend and condemn Amazon here. “Small” hardware projects like the Dash Button and Wand are my favorite kind of corporate experimentation. I’m always excited when a company tries to make an usual hardware product. (The Dash Wand has an honest to goodness barcode scanner!!) This is much preferable to killing these sorts of ideas before they make it out of the lab.

On the other hand, the Dash Buttons are pretty wasteful. It’s fine that they are designed to have a limited lifespan but no markings are going to keep them from going into household garbage when they stop working. What else should Amazon expect users to do? The device obviously has a battery inside but with no clear reminders like a battery door, it’s not going to be obvious to users in the final moments of the device’s life that it should be sent for battery disposal. The use of a typical household battery was quite clever, but the right follow up would have been inclusion of some way to remove it, allowing for unlimited product life and more considerate disposal.

On a more positive note, we’re hoping it’s about to get very easy to pick up huge sacks of Dash Buttons! As they stop working we can break the e-waste cycle by collecting them and providing a new purpose.

Once we start seeing these show up in project drawers there are two paths of exploration worth following. One is finding a set of battery tabs which fit nicely on the existing PCBA so the batteries can be replaced, along with new housings amenable to printing with which to contain it all. At that point the Dash Button can escape the shackles of their finite design lifetimes and run as long as we want them too.

The other course of investigation is obvious: finally get the WiFi working! Though in my experience Broadcom’s WICED branded WiFi parts can get pretty complex, the WINC1500 doesn’t seem to be very exotic. As Adafruit noted in 2016 this module was actually used in the Arduino MKR1000 and WiFi Shield 101, as well as a series of Adafruit boards. So can this be figured out? We’d hope so! As always, if you find new life for an Amazon Dash Button with new enclosures, clever firmware, or anything else we’d love to hear about it!