Sign language – Wikibooks, open books for an open world

Two sign language interpreters working as a team for a school.

Two sign language interpreters working as a team for a school.

A sign language (also signed language) is a language which, instead of acoustically conveyed sound patterns, uses visually transmitted sign patterns (manual communication, body language and lip patterns) to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker’s thoughts. Sign languages commonly develop in deaf communities, which can include interpreters and friends and families of deaf people as well as people who are deaf or hard of hearing themselves.

Wherever communities of deaf people exist, sign languages develop. In fact, their complex spatial grammars are markedly different from the grammars of spoken languages. Hundreds of sign languages are in use around the world and are at the cores of local Deaf cultures. Some sign languages have obtained some form of legal recognition, while others have no status at all.

In addition to sign languages, various signed codes of spoken languages have been developed, such as Signed English and Warlpiri Sign Language.[1] These are not to be confused with languages, oral or signed; a signed code of an oral language is simply a signed mode of the language it carries, just as a writing system is a written mode. Signed codes of oral languages can be useful for learning oral languages or for expressing and discussing literal quotations from those languages, but they are generally too awkward and unwieldy for normal discourse. For example, a teacher and deaf student of English in the United States might use Signed English to cite examples of English usage, but the discussion of those examples would be in American Sign Language.

Several culturally well developed sign languages are a medium for stage performances such as sign-language poetry. Many of the poetic mechanisms available to signing poets are not available to a speaking poet.

History of sign language

[

edit

|

edit source

]

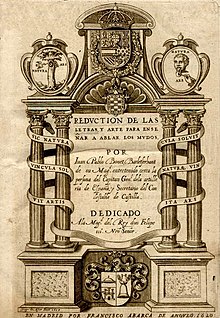

Juan Pablo Bonet, [Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos]

Juan Pablo Bonet, [Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos]

Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup ( help

The written history of sign language began in the 17th century in Spain. In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet published [Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (‘Reduction of letters and art for teaching mute people to speak’) in Madrid. It is considered the first modern treatise of Phonetics and Logopedia, setting out a method of oral education for the deaf people by means of the use of manual signs, in form of a manual alphabet to improve the communication of the mute or deaf people.

From the language of signs of Bonet, Charles-Michel de l’Épée published his alphabet in the 18th century, which has survived basically unchanged until the present time.

In 1755, Abbé de l’Épée founded the first private school for deaf children in Paris; Laurent Clerc was arguably its most famous graduate. He went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut.[2] Gallaudet’s son, Edward Miner Gallaudet founded a school for the deaf in 1857, which in 1864 became Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, the only liberal arts university for and of the deaf in the world.

Generally, each spoken language has a sign language counterpart in as much as each linguistic population will contain Deaf members who will generate a sign language. In much the same way that geographical or cultural forces will isolate populations and lead to the generation of different and distinct spoken languages, the same forces operate on signed languages and so they tend to maintain their identities through time in roughly the same areas of influence as the local spoken languages. This occurs even though sign languages have no relation to the spoken languages of the lands in which they arise. There are notable exceptions to this pattern, however, as some geographic regions sharing a spoken language have multiple, unrelated signed languages. Variations within a ‘national’ sign language can usually be correlated to the geographic location of residential schools for the deaf.

International Sign, formerly known as Gestuno, is used mainly at international Deaf events such as the Deaflympics and meetings of the World Federation of the Deaf. Recent studies claim that while International Sign is a kind of a pidgin, they conclude that it is more complex than a typical pidgin and indeed is more like a full signed language.[3]

Linguistics of sign

[

edit

|

edit source

]

In linguistic terms, sign languages are as rich and complex as any oral language, despite the common misconception that they are not “real languages”. Professional linguists have studied many sign languages and found them to have every linguistic component required to be classed as true languages.[4]

Sign languages are not mime – in other words, signs are conventional, often arbitrary and do not necessarily have a visual relationship to their referent, much as most spoken language is not onomatopoeic. While iconicity is more systematic and wide-spread in sign languages than in spoken ones, the difference is not categorical.[5] Nor are they a visual rendition of an oral language. They have complex grammars of their own, and can be used to discuss any topic, from the simple and concrete to the lofty and abstract.

Sign languages, like oral languages, organize elementary, meaningless units (phonemes; once called cheremes in the case of sign languages) into meaningful semantic units. The elements of a sign are Handshape (or Handform), Orientation (or Palm Orientation), Location (or Place of Articulation), Movement, and Non-manual markers (or Facial Expression), summarised in the acronym HOLME.

Common linguistic features of deaf sign languages are extensive use of classifiers, a high degree of inflection, and a topic-comment syntax. Many unique linguistic features emerge from sign languages’ ability to produce meaning in different parts of the visual field simultaneously. For example, the recipient of a signed message can read meanings carried by the hands, the facial expression and the body posture in the same moment. This is in contrast to oral languages, where the sounds that comprise words are mostly sequential (tone being an exception).

Sign languages’ relationships with oral languages

[

edit

|

edit source

]

A common misconception is that sign languages are somehow dependent on oral languages, that is, that they are oral language spelled out in gesture, or that they were invented by hearing people. Hearing teachers in deaf schools, such as Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, are often incorrectly referred to as “inventors” of sign language.

Manual alphabets (fingerspelling) are used in sign languages, mostly for proper names and technical or specialised vocabulary borrowed from spoken languages. The use of fingerspelling was once taken as evidence that sign languages were simplified versions of oral languages, but in fact it is merely one tool among many. Fingerspelling can sometimes be a source of new signs, which are called lexicalized signs.

On the whole, deaf sign languages are independent of oral languages and follow their own paths of development. For example, British Sign Language and American Sign Language are quite different and mutually unintelligible, even though the hearing people of Britain and America share the same oral language.

Similarly, countries which use a single oral language throughout may have two or more sign languages; whereas an area that contains more than one oral language might use only one sign language. South Africa, which has 11 official oral languages and a similar number of other widely used oral languages is a good example of this. It has only one sign language with two variants due to its history of having two major educational institutions for the deaf which have served different geographic areas of the country.

Spatial grammar and simultaneity

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Sign languages exploit the unique features of the visual medium (sight). Oral language is linear. Only one sound can be made or received at a time. Sign language, on the other hand, is visual; hence a whole scene can be taken in at once. Information can be loaded into several channels and expressed simultaneously. As an illustration, in English one could utter the phrase, “I drove here”. To add information about the drive, one would have to make a longer phrase or even add a second, such as, “I drove here along a winding road,” or “I drove here. It was a nice drive.” However, in American Sign Language, information about the shape of the road or the pleasing nature of the drive can be conveyed simultaneously with the verb ‘drive’ by inflecting the motion of the hand, or by taking advantage of non-manual signals such as body posture and facial expression, at the same time that the verb ‘drive’ is being signed. Therefore, whereas in English the phrase “I drove here and it was very pleasant” is longer than “I drove here,” in American Sign Language the two may be the same length.

In fact, in terms of syntax, ASL shares more with spoken Japanese than it does with English.[6]

Use of signs in hearing communities

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Gesture is a typical component of spoken languages. More elaborate systems of manual communication have developed in places or situations where speech is not practical or permitted, such as cloistered religious communities, scuba diving, television recording studios, loud workplaces, stock exchanges, baseball, hunting (by groups such as the Kalahari bushmen), or in the game Charades. In Rugby Union the Referee uses a limited but defined set of signs to communicate his/her decisions to the spectators. Recently, there has been a movement to teach and encourage the use of sign language with toddlers before they learn to talk, because such young children can communicate effectively with signed languages well before they are physically capable of speech. This is typically referred to as Baby Sign. There is also movement to use signed languages more with non-deaf and non-hard-of-hearing children with other causes of speech impairment or delay, for the obvious benefit of effective communication without dependence on speech.

On occasion, where the prevalence of deaf people is high enough, a deaf sign language has been taken up by an entire local community. Famous examples of this include Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language in the USA, Kata Kolok in a village in Bali, Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana and Yucatec Maya sign language in Mexico. In such communities deaf people are not socially disadvantaged.

Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites. They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, and Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

A pidgin sign language arose among tribes of American Indians in the Great Plains region of North America (see Plains Indian Sign Language). It was used to communicate among tribes with different spoken languages. There are especially users today among the Crow, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages.

Telecommunications facilitated signing

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Video Interpreter sign used at VRS/VRI service locations (Courtesy: Significan’t SignVideo Services)

Video Interpreter sign used at VRS/VRI service locations (Courtesy: Significan’t SignVideo Services)

One of the first demonstrations of the ability for telecommunications to help sign language users communicate with each other occurred when AT&T’s videophone (trademarked as the ‘Picturephone’) was introduced to the public at the 1964 New York World’s Fair –two deaf users were able to freely communicate with each other between the fair and another city.[7] Various organizations have also conducted research on signing via videotelephony.

Sign language interpretation services via Video Remote Interpreting (VRI) or a Video Relay Service (VRS) are useful in the present-day where one of the parties is deaf, hard-of-hearing or speech-impaired (mute). In such cases the interpretation flow is normally within the same principal language, such as French Sign Language (FSL) to spoken French, Spanish Sign Language (SSL) to spoken Spanish, British Sign Language (BSL) to spoken English, and American Sign Language (ASL) also to spoken English (since BSL and ASL are completely distinct), etc…. Multilingual sign language interpreters, who can also translate as well across principal languages (such as to and from SSL, to and from spoken English), are also available, albeit less frequently. Such activities involve considerable effort on the part of the translator, since sign languages are distinct natural languages with their own construction and syntax, different from the aural version of the same principal language.

A deaf or mute person using a Video Relay Service to communicate with a hearing person (Courtesy: Significan’t SignVideo Services)

A deaf or mute person using a Video Relay Service to communicate with a hearing person (Courtesy: Significan’t SignVideo Services)

With video interpreting, sign language interpreters work remotely with live video and audio feeds, so that the interpreter can see the deaf or mute party, and converse with the hearing party, and vice versa. Much like telephone interpreting, video interpreting can be used for situations in which no on-site interpreters are available. However, video interpreting cannot be used for situations in which all parties are speaking via telephone alone. VRI and VRS interpretation requires all parties to have the necessary equipment. Some advanced equipment enables interpreters to remotely control the video camera, in order to zoom in and out or to point the camera toward the party that is signing.

Home sign

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Sign systems are sometimes developed within a single family. For instance, when hearing parents with no sign language skills have a deaf child, an informal system of signs will naturally develop, unless repressed by the parents. The term for these mini-languages is home sign (sometimes homesign or kitchen sign).[8]

Home sign arises due to the absence of any other way to communicate. Within the span of a single lifetime and without the support or feedback of a community, the child naturally invents signals to facilitate the meeting of his or her communication needs. Although this kind of system is grossly inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and it comes nowhere near meeting the standards linguists use to describe a complete language, it is a common occurrence. No type of Home Sign is recognized as an official language.

Classification of sign languages

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Although deaf sign languages have emerged naturally in deaf communities alongside or among spoken languages, they are unrelated to spoken languages and have different grammatical structures at their core. A group of sign “languages” known as manually coded languages are more properly understood as signed modes of spoken languages, and therefore belong to the language families of their respective spoken languages. There are, for example, several such signed encodings of English.

There has been very little historical linguistic research on sign languages, and few attempts to determine genetic relationships between sign languages, other than simple comparison of lexical data and some discussion about whether certain sign languages are dialects of a language or languages of a family. Languages may be spread through migration, through the establishment of deaf schools (often by foreign-trained educators), or due to political domination.

Language contact is common, making clear family classifications difficult — it is often unclear whether lexical similarity is due to borrowing or a common parent language. Contact occurs between sign languages, between signed and spoken languages (Contact Sign), and between sign languages and gestural systems used by the broader community. One author has speculated that Adamorobe Sign Language may be related to the “gestural trade jargon used in the markets throughout West Africa”, in vocabulary and areal features including prosody and phonetics.[9]

- BSL, Auslan and NZSL are usually considered to belong to a language family known as BANZSL. Maritime Sign Language and South African Sign Language are also related to BSL.[10]

- Japanese Sign Language, Taiwanese Sign Language and Korean Sign Language are thought to be members of a Japanese Sign Language family.

- There are a number of sign languages that emerged from French Sign Language (LSF), or were the result of language contact between local community sign languages and LSF. These include: French Sign Language, Quebec Sign Language, American Sign Language, Irish Sign Language, Russian Sign Language, Dutch Sign Language, Flemish Sign Language, Belgian-French Sign Language, Spanish Sign Language, Mexican Sign Language, Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) and others.

- A subset of this group includes languages that have been heavily influenced by American Sign Language (ASL), or are regional varieties of ASL. Bolivian Sign Language is sometimes considered a dialect of ASL. Thai Sign Language is a mixed language derived from ASL and the native sign languages of Bangkok and Chiang Mai, and may be considered part of the ASL family. Others possibly influenced by ASL include Ugandan Sign Language, Kenyan Sign Language, Philippine Sign Language and Malaysian Sign Language.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests that Finnish Sign Language, Swedish Sign Language and Norwegian Sign Language belong to a Scandinavian Sign Language family.

- Icelandic Sign Language is known to have originated from Danish Sign Language, although significant differences in vocabulary have developed in the course of a century of separate development.

- Israeli Sign Language was influenced by German Sign Language.

- According to a SIL report, the sign languages of Russia, Moldova and Ukraine share a high degree of lexical similarity and may be dialects of one language, or distinct related languages. The same report suggested a “cluster” of sign languages centered around Czech Sign Language, Hungarian Sign Language and Slovakian Sign Language. This group may also include Romanian, Bulgarian, and Polish sign languages.

- Known isolates include Nicaraguan Sign Language, Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language, and Providence Island Sign Language.

- Sign languages of Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Iraq (and possibly Saudi Arabia) may be part of a sprachbund, or may be one dialect of a larger Eastern Arabic Sign Language.

The only comprehensive classification along these lines going beyond a simple listing of languages dates back to 1991.[11] The classification is based on the 69 sign languages from the 1988 edition of Ethnologue that were known at the time of the 1989 conference on sign languages in Montreal and 11 more languages the author added after the conference.[12]

Classification of sign languages[13]

Primary

Single

Primary

Group

Alternative

Single

Alternative

Group

Prototype-A

7

1

7

2

Prototype-R

18

1

1

–

BSL(bfi)-derived

8

–

–

–

DGS(gsg)-derived

2

–

–

–

JSL-derived

2

–

–

–

LSF(fsl)-derived

30

–

–

–

LSG-derived

1

–

–

–

In his classification, the author distinguishes between primary and alternative sign languages[14] and, subcategorically, between languages recognizable as single languages and languages thought to be composite groups.[15] The prototype-A class of languages includes all those sign languages that seemingly cannot be derived from any other language. Prototype-R languages are languages that are remotely modelled on prototype-A language by a process Kroeber (1940) called “stimulus diffusion”. The classes of BSL(bfi)-, DGS(gsg)-, JSL-, LSF(fsl)- and LSG-derived languages represent “new languages” derived from prototype languages by linguistic processes of creolization and relexification.[16] Creolization is seen as enriching overt morphology in “gesturally signed” languages, as compared to reducing overt morphology in “vocally signed” languages.[17]

Typology of sign languages

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Linguistic typology (going back on Edward Sapir) is based on word structure and distinguishes morphological classes such as agglutinating/concatenating, inflectional, polysynthetic, incorporating, and isolating ones.

Sign languages vary in syntactic typology as there are different word orders in different languages. For example, ÖGS is Subject-Object-Verb while ASL is Subject-Verb-Object. Correspondance to the surrounding spoken languages is not improbable.

Morphologically speaking, wordshape is the essential factor. Canonical wordshape results from the systematic pairing of the binary values of two features, namely syllabicity (mono- or poly-) and morphemicity (mono- or poly-). Brentari[18][19] classifies sign languages as a whole group determined by the medium of communication (visual instead of auditive) as one group with the features monosyllabic and polymorphemic. That means, that via one syllable (i.e. one word, one sign) several morphemes can be expressed, like subject and object of a verb determine the direction of the verb’s movement (inflection). This is necessary for sign languages to assure a comparible production rate to spoken languages, since producing one sign takes much longer than uttering one word – but on a sentence to sentence comparison, signed and spoken languages share approximately the same speed.[20]

Written forms of sign languages

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Sign language differs from oral language in its relation to writing. The phonemic systems of oral languages are primarily sequential: that is, the majority of phonemes are produced in a sequence one after another, although many languages also have non-sequential aspects such as tone. As a consequence, traditional phonemic writing systems are also sequential, with at best diacritics for non-sequential aspects such as stress and tone.

Sign languages have a higher non-sequential component, with many “phonemes” produced simultaneously. For example, signs may involve fingers, hands, and face moving simultaneously, or the two hands moving in different directions. Traditional writing systems are not designed to deal with this level of complexity.

Partially because of this, sign languages are not often written. Most deaf signers read and write the oral language of their country. However, there have been several attempts at developing scripts for sign language. These have included both “phonetic” systems, such as HamNoSys (the Hamburg Notational System) and SignWriting, which can be used for any sign language, and “phonemic” systems such as the one used by William Stokoe in his 1965 Dictionary of American Sign Language, which are designed for a specific language.

These systems are based on iconic symbols. Some, such as SignWriting and HamNoSys, are pictographic, being conventionalized pictures of the hands, face, and body; others, such as the Stokoe notation, are more iconic. Stokoe used letters of the Latin alphabet and Arabic numerals to indicate the handshapes used in fingerspelling, such as ‘A’ for a closed fist, ‘B’ for a flat hand, and ‘5’ for a spread hand; but non-alphabetic symbols for location and movement, such as ‘[]’ for the trunk of the body, ‘×’ for contact, and ‘^’ for an upward movement. David J. Peterson has attempted to create a phonetic transcription system for signing that is ASCII-friendly known as the Sign Language International Phonetic Alphabet (SLIPA).

SignWriting, being pictographic, is able to represent simultaneous elements in a single sign. The Stokoe notation, on the other hand, is sequential, with a conventionalized order of a symbol for the location of the sign, then one for the hand shape, and finally one (or more) for the movement. The orientation of the hand is indicated with an optional diacritic before the hand shape. When two movements occur simultaneously, they are written one atop the other; when sequential, they are written one after the other. Neither the Stokoe nor HamNoSys scripts are designed to represent facial expressions or non-manual movements, both of which SignWriting accommodates easily, although this is being gradually corrected in HamNoSys.

Primate use of sign language

[

edit

|

edit source

]

There have been several notable examples of scientists teaching non-human primates basic signs in order to communicate with humans.[21] Notable examples are:-

- Chimpanzees: Washoe and Loulis

- Gorillas: Michael and Koko.

Gestural theory of human language origins

[

edit

|

edit source

]

The gestural theory states that vocal human language developed from a gestural sign language.[22] An important question for gestural theory is what caused the shift to vocalization.[23]

A demonstration of the French Sign Language word [demander]

Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup ( help

to ask) three times: “Me-ask-you,” “you-ask-me,” and “one-ask-them.”

- ↑

This inclusion of the Warlpiri Sign Language (and other aboriginal sign languages) among the Manually Coded Languages, based on the presumption that natural sign languages can only develop in deaf communities, is now widely disputed (Madell 1998, O’Reilly 2005). As to their use in deaf communities, the 2008 version of the 15th edition of Ethnologue reports that “several such sign languages are also used by deaf persons.” [1]

- ↑

Canlas (2006).

- ↑

Cf. Supalla, Ted & Rebecca Webb (1995). “The grammar of international sign: A new look at pidgin languages.” In: Emmorey, Karen & Judy Reilly (eds). Language, gesture, and space. (International Conference on Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research) Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, pp. 333-352; McKee R. & J. Napier J. (2002). “Interpreting in International Sign Pidgin: an analysis.” Journal of Sign Language Linguistics 5(1).

- ↑

This latter conception is no longer disputed as can be seen from the fact that sign language experts are mostly linguists.

- ↑

Johnston (1989).

- ↑

Nakamura (1995).

- ↑

Bell Laboratories RECORD (1969) A collection of several articles on the AT&T Picturephone (then about to be released) Bell Laboratories, Pg.134-153 & 160-187, Volume 47, No. 5, May/June 1969;

- ↑

Susan Goldin-Meadow (Goldin-Meadow 2003, Van Deusen, Goldin-Meadow & Miller 2001) has done extensive work on home sign systems. Adam Kendon (1988) published a seminal study of the homesign system of a deaf Enga woman from the Papua New Guinea highlands, with special emphasis on iconicity.

- ↑

Frishberg (1987). See also the classification of Wittmann (1991) for the general issue of jargons as prototypes in sign language glottogenesis.

- ↑

See Gordon (2008), under nsr [2] and sfs [3]

- ↑

Henri Wittmann (1991). The classification is said to be typological satisfying Jakobson’s condition of genetic interpretability.

- ↑

Wittmann’s classification went into Ethnologue’s database where it is still cited. [4] The subsequent edition of Ethnologue in 1992 went up to 81 sign languages and ultimately adopting Wittmann’s distinction between primary and alternates sign langues (going back ultimately to Stokoe 1974) and, more vaguely, some other of his traits. The 2008 version of the 15th edition of Ethnologue is now up to 124 sign languages.

- ↑

To the extent that Wittmann’s language codes are different from SIL codes, the latter are given within parentheses

- ↑

Wittmann adds that this taxonmic criteron is not really applicable with any scientific rigor: Alternative sign languages, to the extent that they are full-fledged natural languages (and therefore included in his survey), are mostly used by the deaf as well; and some primary sign languages (such as ASL(ase) and ADS) have acquired alternative usages.

- ↑

Wittmann includes in this class ASW (composed of at least 14 different languages), MOS(mzg), HST (distinct from the LSQ>ASL(ase)-derived TSQ) and SQS. In the meantime since 1991, HST has been recognized as being composed of BFK, CSD, HAB, HAF, HOS, LSO.

- ↑

Wittmann’s references on the subject, besides his own work on creolization and relexification in “vocally signed” languages, include papers such as Fischer (1974, 1978), Deuchar (1987) and Judy Kegl’s pre-1991 work on creolization in sign languages.

- ↑

Wittmann’s explanation for this is that models of acquisition and transmission for sign languages are not based on any typical parent-child relation model of direct transmission which is inducive to variation and change to a greater extent. He notes that sign creoles are much more common than vocal creoles and that we can’t know on how many successive creolizations prototype-A sign languages are based prior to their historicity.

- ↑

Brentari, Diane (1998): A prosodic model of sign language phonology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; cited in Hohenberger (2007) on p. 349

- ↑

Brentari, Diane (2002): Modality differences in sign language phonology and morphophonemics. In: Richard P. Meier, kearsy Cormier, and David Quinto-Pozocs (eds.), 35-36; cited in Hohenberger (2007) on p. 349

- ↑

Hohenberger, Annette: The possible range of variation between sign languages: Universal Grammar, modality, and typological aspects; in: Perniss, Pamela M., Roland Pfau and Markus Steinbach (Eds.): Visible Variation. Comparative Studies on Sign Language Structure; (Reihe Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM] 188). Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter 2007

- ↑

Premack & Pemack (1983), Premack (1985), Wittmann (1991).

- ↑

Hewes (1973), Premack & Premack (1983), Kimura (1993), Newman (2002), Wittmann (1980, 1991)

- ↑

Kolb & Whishaw (2003)

- Aronoff, Mark, Meir, Irit & Wendy Sandler (2005). “The Paradox of Sign Language Morphology.” Language 81 (2), 301-344.

- Branson, J., D. Miller, & I G. Marsaja. (1996). “Everyone here speaks sign language, too: a deaf village in Bali, Indonesia.” In: C. Lucas (ed.): Multicultural aspects of sociolinguistics in deaf communities. Washington, Gallaudet University Press, pp. 39-5.

- Canlas, Loida (2006). “Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World.” The Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University.[5]

- Deuchar, Margaret (1987). “Sign languages as creoles and Chomsky’s notion of Universal Grammar.” Essays in honor of Noam Chomsky, 81-91. New York: Falmer.

- Emmorey, Karen; & Lane, Harlan L. (Eds.). (2000). The signs of language revisited: An anthology to honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-3246-7.

- Fischer, Susan D. (1974). “Sign language and linguistic universals.” Actes du Colloque franco-allemand de grammaire générative, 2.187-204. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Fischer, Susan D. (1978). “Sign languages and creoles.” Siple 1978:309-31.

- Frishberg, Nancy (1987). “Ghanaian Sign Language.” In: Cleve, J. Van (ed.), Gallaudet encyclopaedia of deaf people and deafness. New York: McGraw-Gill Book Company.

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan, 2003, The Resilience of Language: What Gesture Creation in Deaf Children Can Tell Us About How All Children Learn Language, Psychology Press, a subsidiary of Taylor & Francis, New York, 2003

- Gordon, Raymond, ed. (2008). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th edition. SIL International, ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6, ISBN 1-55671-159-X. Web version.[6] Sections for primary sign languages[7] and alternative ones[8].

- Groce, Nora E. (1988). Everyone here spoke sign language: Hereditary deafness on Martha’s Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27041-X.

- Healy, Alice F. (1980). Can Chimpanzees learn a phonemic language? In: Sebeok, Thomas A. & Jean Umiker-Sebeok, eds, Speaking of apes: a critical anthology of two-way communication with man. New York: Plenum, 141-143.

- Hewes, Gordon W. (1973). “Primate communication and the gestural origin of language.” Current Anthropology 14.5-32.

- Johnston, Trevor A. (1989). Auslan: The Sign Language of the Australian Deaf community. The University of Sydney: unpublished Ph.D. dissertation.[9]

- Kamei, Nobutaka (2004). The Sign Languages of Africa, “Journal of African Studies” (Japan Association for African Studies) Vol.64, March, 2004. [NOTE: Kamei lists 23 African sign languages in this article].

- Kegl, Judy (1994). “The Nicaraguan Sign Language Project: An Overview.” Signpost 7:1.24-31.

- Kegl, Judy, Senghas A., Coppola M (1999). “Creation through contact: Sign language emergence and sign language change in Nicaragua.” In: M. DeGraff (ed), Comparative Grammatical Change: The Intersection of Language Acquisistion, Creole Genesis, and Diachronic Syntax, pp.179-237. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kegl, Judy (2004). “Language Emergence in a Language-Ready Brain: Acquisition Issues.” In: Jenkins, Lyle, (ed), Biolinguistics and the Evolution of Language. John Benjamins.

- Kendon, Adam. (1988). Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia: Cultural, Semiotic and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kimura, Doreen (1993). Neuromotor Mechanisms in Human Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1979). The signs of language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80795-2.

- Kolb, Bryan, and Ian Q. Whishaw (2003). Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 5th edition, Worth Publishers.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1940). “Stimulus diffusion.” American Anthropologist 42.1-20.

- Krzywkowska, Grazyna (2006). “Przede wszystkim komunikacja”, an article about a dictionary of Hungarian sign language on the internet Template:Pl icon.

- Lane, Harlan L. (Ed.). (1984). The Deaf experience: Classics in language and education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19460-8.

- Lane, Harlan L. (1984). When the mind hears: A history of the deaf. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-50878-5.

- Madell, Samantha (1998). Warlpiri Sign Language and Auslan – A Comparison. M.A. Thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.[10]

- Nakamura, Karen (1995). “About American Sign Language.” Deaf Resourec Library, Yale University.[11]

- Newman, A. J., et al. (2002). “A Critical Period for Right Hemisphere Recruitment in American Sign Language Processing”. Nature Neuroscience 5: 76–80.

- O’Reilly, S. (2005). Indigenous Sign Language and Culture; the interpreting and access needs of Deaf people who are of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in Far North Queensland. Sponsored by ASLIA, the Australian Sign Language Interpreters Association.

- Padden, Carol; & Humphries, Tom. (1988). Deaf in America: Voices from a culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19423-3.

- Poizner, Howard; Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1987). What the hands reveal about the brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Premack, David, & Ann J. Premack (1983). The mind of an ape. New York: Norton.

- Premack, David (1985) “‘Gavagai!’ or the future of the animal language controversy”. Cognition 19, 207-296

- Sacks, Oliver W. (1989). Seeing voices: A journey into the world of the deaf. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06083-0.

- Sandler, Wendy (2003). Sign Language Phonology. In William Frawley (Ed.), The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Linguistics.[12]

- Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2001). Natural sign languages. In M. Aronoff & J. Rees-Miller (Eds.), Handbook of linguistics (pp. 533-562). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20497-0.

- Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2006). Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Stiles-Davis, Joan; Kritchevsky, Mark; & Bellugi, Ursula (Eds.). (1988). Spatial cognition: Brain bases and development. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0046-8; ISBN 0-8058-0078-6.

- Stokoe, William C. (1960, 1978). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American deaf. Studies in linguistics, Occasional papers, No. 8, Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo. 2d ed., Silver Spring: Md: Linstok Press.

- Stokoe, William C. (1974). Classification and description of sign languages. Current Trends in Linguistics 12.345-71.

- Van Deusen-Phillips S.B., Goldin-Meadow S., Miller P.J., 2001. Enacting Stories, Seeing Worlds: Similarities and Differences in the Cross-Cultural Narrative Development of Linguistically Isolated Deaf Children, Human Development, Vol. 44, No. 6.

- Wittmann, Henri (1980). “Intonation in glottogenesis.” The melody of language: Festschrift Dwight L. Bolinger, in: Linda R. Waugh & Cornelius H. van Schooneveld, 315-29. Baltimore: University Park Press.[13]

- Wittmann, Henri (1991). “Classification linguistique des langues signées non vocalement.” Revue québécoise de linguistique théorique et appliquée 10:1.215-88.[14]

Note: the articles for specific sign languages (e.g. ASL or BSL) may contain further external links, e.g. for learning those languages.