Secrets of the Amazon: giant anacondas and floating forests, an interview with Paul Rosolie

Paul Rosolie leads volunteer expeditions into the Peruvian rainforest with an aim towards education and grassroots conservation. Mongabay.com’s eighth in its series of interviews with ‘Young Scientists’.

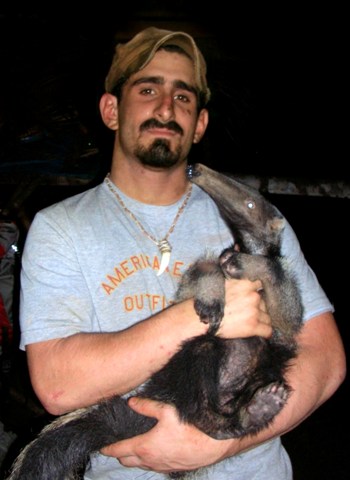

At twenty-two Paul Rosolie has seen more adventure than many of us will in our lifetime. First visiting the Amazon at eighteen, Rosolie has explored strange jungle ecosystems, caught anaconda and black caiman bare-handed, joined indigenous hunting expeditions, led volunteer expeditions, and hand-raised a baby giant anteater.

“Rainforests were my childhood obsession,” Rosolie told Mongabay.com. “For as long as I can remember, going to the Amazon had been my dream […] In those first ten minutes [of visiting], cowering under the bellowing calls of howler monkeys, I saw trails of leaf cutter ants under impossibly large, vine-tangled trees; a flock of scarlet macaws crossed the sky like a brilliant flying rainbow. I saw a place where nature was in its full; it is the most amazing place on earth.”

Paul Rosolie inspecting a 15ft+ female for facial parasites such as ticks. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

Today Rosolie is a full-time environmental studies major at Ramapo College in New Jersey. But during breaks he leads tourist and volunteer expeditions (Tamandua Rainforest Expeditions) deep into the Peruvian Amazon near the Tambopata River. Rosolie has teamed up with Juan Julio Duran and the local indigenous tribe, called the Infierno (named by missionaries), to run the tours, as well as explore, survey, and conserve the area.

Recently, the local tribe sent Rosolie and Duran to a place both legendary and ecologically marvelous: a massive lake with a “raft of vegetation and grass which supports a smaller dwarf forest,” Rosolie says. The ecosystem is strong enough to walk on—at least in parts.

“Walking on the floating forest at night is a surreal and very spooky experience. The floating part isn’t very stable, one wrong step and you get plunged into the lake. It was an intimidating place but with careful navigation we found a completely alien environment. As we walked, we passed only the tops of the aguaje palms whose base lay rooted to the lake’s floor forty or fifty feet below,” he says.

While this unique ecosystem is home to a number of animals, including “three species of caiman, two species of owl, numerous fish (which we were unable to identify), and a tremendous tarantula population”—all seen on the first night—the big (literally) inhabitants are the anacondas.

During their first expedition to the dwarf forest, Duran and Rosolie came upon the biggest anaconda they have ever encountered: “We spotted two tremendous anacondas. The largest was more than double the size of the largest anaconda [Duran] and I have ever measured (15ft 4 inches). She was so large it would have taken eight people to restrain her on land; on the floating forest there was no chance. When she saw us she started moving away. We both wrapped our arms around her and did our best to restrain her for measurements and documentation, but it was like trying to stop a bus, she was way too strong. She bolted for the water with us holding onto her. Hanging on longer would have meant following her into the water below the floating forest. We were left soaked and panting – in complete disbelief of what we had just seen.”

Anaconda close-up. Photo by Gowri Varanashi.

Rosolie estimates that she was at least 25 feet long with a 70 inch girth—given the fact that his six foot arm-span could barely reach around her body.

“Snakes measuring over twenty feet are extremely rare,” Rosolie says, “this one was a living legend. In future explorations, once again spotting her will be one of my primary goals.”

Rosolie believes that the dwarf forest on the lake may be an anaconda mating ground, given the number of snake tracks they have seen there and the lack of suitable prey.

“To my knowledge, and the knowledge of the people of Infierno, there is nowhere like it the region,” Rosolie says.

Rosolie’s volunteer trips, named Tamandua Expeditions, helps raise eco-tourism funds for the Infierno people, whose area is threatened by development, road building, oil leases, hunting, bushmeat demand, and gold mining.

“We have raised money that has contributed to permanently protecting a 7000 square hectare area of primary forest,” explains Rosolie. “Recently we have begun a new project within the Infierno community itself. By basing volunteer expeditions on Infierno territory we are supporting the community’s ambitions to pursue revenue through ecotourism. This, combined with the discovery of the floating forest ecosystem has helped convince community decision makers to abandon plans of creating several new roads into primary forest areas.”

A yellow footed tortoise, one of the most threatened species in the area. This individual was destined for the soup pot, but was rescued and released by Tamandua. Photo by Gowri Varanashi.

Having tourists come from around the world has also brought increasing conservation awareness to the Infierno community as well.

“For my friends in Infierno, seeing the interest and appreciation which visitors have for their home (the rainforest) and way of life, is an eye opening experience. They take great pride in showing volunteers the ways of the forest, skills such as how to observe animals, what fruits and nuts are edible, what vines are needed to make brooms and hats, and how to use a machete for just about everything,” says Rosolie, who adds that education and the desire to draw eco-tourists has led to a decline in hunting by the Infierno.

“I try to lead volunteers on an adventure that they will never forget – which is thankfully the one easy part,” Rosolie says of his expeditions. “When people see fire-red macaws crossing the sky for the first time, or explore the giant buttress roots of a kapok tree, or find themselves holding a live spectacled caiman, I know that the jungle has done my work for me – they are hooked.”

In a March interview with Mongabay.com, Paul Rosolie spoke about his expeditions into the Amazon, the local Infierno community, anacondas and black caiman, grassroots conservation work, and his recent discovery of a strange floating dwarf forest thriving on a carpet of vegetation.

AN INTERVIEW WITH PAUL ROSOLIE

Mongabay: How did you become interested in wildlife? What is your background?

A tapir emerging from the river and heading for the cover of the forest. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: I’ve always been passionate about wildlife and the natural world. Some of my earliest memories are of my parents taking me on hikes in the woods, or teaching me the difference between African and Asian elephants, or how to recognize the difference between tree species. I grew up hiking, camping, catching snakes, and raising praying mantises each summer.

I couldn’t have been more than eight years old when I remember hearing about a species of turtle of which there was only one left. The species was about to go extinct. As a child who loved wildlife above all else, it was the most terrible thing I had ever heard. It was my first encounter with the concept of extinction. To think that any species could be gone forever at the hands of humans was more than I could fathom. That story made an impression on me which never left; I have been passionate about conservation ever since.

And while I always found classrooms dull, my dissatisfaction with conventional education reached its peak during sophomore year of high school. So, with my parents’ encouragement (can you believe that!) I left high school and started college. Soon after turning eighteen I followed my dream of visiting the Peruvian Amazon. There I fell in love with the pristine primary forests of the Madre de Dios lowlands. But it was later that same year, while on a study abroad program through Columbia University in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest that I learned the true value of what I had experienced in Peru. The near total destruction and complete fragmentation of the once great biome was a sobering contrast to what I had seen in the Amazon. It instilled a fear in me which was reinforced by similarly grim images of rainforest decimation which I encountered during work in Indonesia and India. It is because of these experiences that I have chosen to dedicate myself to defending the Amazon.

I will be finishing my undergraduate in environmental studies at Ramapo College of New Jersey this May.

Mongabay: You first volunteered in the Amazon at the young age of eighteen—what drew you there?

An arrow frog. Photo by Gowri Varanashi.

Paul Rosolie: Rainforests were my childhood obsession. For as long as I can remember, going to the Amazon had been my dream. I have always been aware of the destruction occurring in rainforests around the world and by age 17 the sense of urgency was unbearable; I had to go. I had to see for myself if it really was as incredible and vast as documentaries showed it to be. At the time I had no way of knowing that it would far surpass even my wildest expectations. It took about ten minutes in the jungle before I knew without a doubt that this was where I belonged. In those first ten minutes, cowering under the bellowing calls of howler monkeys I saw trails of leaf cutter ants under impossibly large, vine-tangled trees; a flock of scarlet macaws crossed the sky like a brilliant flying rainbow. I saw a place where nature was in its full; it is the most amazing place on earth.

Mongabay: How do you balance your conservation work in Peru with your studies back in the US?

Paul Rosolie: So far I have been restricted to running trips between semesters and during the summer. I use my time at school in the states to recruit volunteers and plan expeditions.

Mongabay: How did you end up working with the Infierno people on Peru’s Tambopata River?

Paul Rosolie: My good friend and partner in Tamandua expeditions is a man named Juan Julio Duran (or JJ). He was one of the expedition leaders of my first trip to the jungle. I began learning from him and as our friendship grew, I became more and more familiar with his family and the other members of the community. Over the past few years I have tagged along on numerous expeditions into indigenous hunting grounds with men from Infierno. During these forays, mostly in the Tambopata Reserve and Bahuaja-Sonene Natinal Park, they would search for peccary, fish, and forest foul to hunt; I would search for wildlife to study and photograph. It was then that I honed my jungle skills, and became addicted to the indescribable feeling of being truly deep in the jungle, away from civilization for days on end.

THE DWARF FOREST AND ANACONDAS

Normally 50+ feet in the air, the top of this aguaje palm stands only several feet from the surface of the lake – and the floating vegetation that covers it. Soaked to the chest from a night of exploring and plunging, I am standing next to it for scale. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

Mongabay: Locals recently led you to a startling place. Will you tell us about the dwarf forest on the lake?

Paul Rosolie: For years I had been hearing about a lake that was somehow special. Everyone in the community had a profound respect for it because it was rumored to have tremendous anacondas and full grown giant black caiman. I suspected all the hype to be mostly exaggeration. But when we launched our first exploration of the place, we instead found the legends to be understated. The lake is huge, and is surrounded by a palm forest swamp system that stretches for miles. But the most incredible part is that floating on top of the water’s surface is a raft of vegetation and grass which supports a smaller dwarf forest. This “raft” is tremendous, we still don’t know its exact size, but it is arranged in a patchwork that covers over 80% of the lake’s surface. Acting as support pillars for the vegetation raft and dwarf forest, are the tops of aguaje palm trees which are rooted to the lake’s bottom.

Walking on the floating forest at night is a surreal and very spooky experience. The floating part isn’t very stable, one wrong step and you get plunged into the lake. It was an intimidating place but with careful navigation we found a completely alien environment. As we walked, we passed only the tops of the aguaje palms whose base lay rooted to the lake’s floor forty or fifty feet below. The value of this ecosystem as an isolated habitat was immediately evident to us, and during the night of our first exploration we recorded three species of caiman, two species of owl, numerous fish (which we were unable to identify), and a tremendous tarantula population. To my knowledge, and the knowledge of the people of infierno, there is nowhere like it the region.

Mongabay: Will you also tell us about your first encounter with anacondas in the lake?

A volunteer demonstrating the placid nature of the world’s largest snake species. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: On our very first night exploring the floating forest we immediately noticed drag marks of all sizes winding through the grass, areas where something had flattened the vegetation. JJ suspected from the start that they were anaconda pathways, but I was skeptical because there were simply too many, and some were far too large. Some measured over 20inches wide. But the answer to our questions came at 2am – when we spotted two tremendous anacondas. The largest was more than double the size of the largest anaconda JJ and I have ever measured (15ft 4inches). She was so large it would have taken eight people to restrain her on land; on the floating forest there was no chance. When she saw us she started moving away. We both wrapped our arms around her and did our best to restrain her for measurements and documentation, but it was like trying to stop a bus, she was way too strong. She bolted for the water with us holding onto her. Hanging on longer would have meant following her into the water below the floating forest. We were left soaked and panting – in complete disbelief of what we had just seen.

Mongabay: How many anacondas have you found in this strange ecosystem? What is the largest you have recorded?

Paul Rosolie: From catching 15ft individuals on a fairly regular basis, we have a good frame of reference to verify that the female was saw that first night was significantly larger than double any we had previously encountered. The only actual measurement we have is that my arms barely touched around her body and I have a 6’ arm span. This means that the snake had a girth of something like 70 inches. We estimate her length to be easily upwards of 25ft. Snakes measuring over twenty feet are extremely rare; this one was a living legend. In future explorations, once again spotting her will be one of my primary goals. Although we have been seeing evidence (tracks) of 25ft+ range individuals in extremely remote areas forest for years, actually photographing and documenting an anaconda of that size would be huge!

Mongabay: What ecological significance do you think this place has?

A large female anaconda with its constricted prey – a collared peccary. Spending the dry months in the sanctuary of the floating forest, this female was found during January at the base of an active mammal colpa, taking advantage of the abundance of food. Photo by Gowri Varanashi.

Paul Rosolie: Our research so far indicates that in the dry season, when water in the forest is low or absent, the anacondas travel to the protection and moisture provided by the floating forest. The soft vegetation, isolation from predators, and copious water make it a perfect location for mating, which we suspect to be the main reason for migration to the lake. It is a theory supported by the fact that while the floating forest offers a social sanctuary, the anacondas would have little or no access to large prey animals while living there. As a result, during the rainy season as the forest floods, the anacondas migrate away from the lake into the forest. Using forest streams as navigation highways, they diffuse into the primary forest floodplain and it is there that they do the majority of their hunting. In January of this year while exploring the Infierno territory, JJ, his brother Federico, and I were following a herd of collared peccary when we came across a 14ft female in a stream constricting one of the pigs we had been following, it was an incredible image!

Because the floating forest hosts a large migration of an apex predator species, this location most likely impacts the surrounding ecosystem in a profound way. Since anacondas are born very small and grow very large, their predation affects many levels of the food chain. Their usual diet includes caiman, birds, agoutis, capybara, peccary, monkeys, and much more. There was even a confirmed case of a dead anaconda found with a nine foot boa constrictor in its stomach. Other species found around the floating forest habitat include peccary, tapir, ocelot, giant armadillo, giant anteater, puma, and tyra among others.

The fossilized lower jaw of what is suspected to be from an extinct giant ground sloth. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Mongabay: What are some other notable species that you have recorded in the Tambopata region?

Paul Rosolie: The region is notoriously rich in biodiversity. Some of my favorites to see are blue and yellow macaws, spider monkeys, howler monkeys, tapir, peccary, caiman, and an incredible diversity of frogs. Other notable wildlife that we have recorded are giant anteaters, giant armadillos, king vulture, blue morpho butterfly, brocket deer, tamanduas, sloths, harpy eagle, toucans, and a tremendously healthy population of jaguar. Some of our rarer finds include the black caiman, several unidentified species of snake, the Amazon leaf frog, ocelots, and the gallywasp lizard. On two occasions we have even encountered the planet’s largest lepidopteran, the ghost moth, with a wingspan of 12 inches. Also worthy of note is the finding of a fossilized lower jaw bone from an extinct giant ground sloth.

Mongabay: You’ve discovered a healthy population of black caiman in the region. Will you tell us about this species and why your discovery is important?

Paul Rosolie: Today there are pockets of black caiman scattered throughout the region, but fully grown adults are rare. In the past fifty years the skin trade has brought their numbers to dangerously low levels. Although the skin trade has subsided they still face ‘pest’ status and are frequently killed by fearful humans. Having been almost completely exterminated for years now, they are slowly coming back to the area. However, they are being met with opposition similar to that of wolves in the U.S. – another re-emerging apex predator. People are used to life without them.

I encountered one farmer who showed me the carcass of a 16 foot mother caiman. Close by was her nest which had been ravaged by predators in the absence of her protection. Although their population seems to be on the rise once again, it is a slow and hazardous recovery. Being the largest predator in the Amazon, their full return could have a dramatic effect on riparian fauna and on the health of the entire ecosystem. They are a stunning species to observe.

THE INFIERNOS

Mongabay: Will you tell us about the Infiernos?

A twenty year-old Infierno getting his first up close look at a caiman. Caiman, like snakes, are often misunderstood. Photo by Gowri Varanashi.

Paul Rosolie: The Infierno community is a mix of indigenous Ese’eja and Andean colonists. The community consists of about 90 families and covers approximately 25,000 acres of rainforest on both sides of the Tamboptata. Like many native communities today, Infierno is made up of people who live varied lifestyles. Some still live primarily out of the forest—hunting, fishing, farming, and gathering from the surrounding jungle. Many are Brazil nut farmers, many harvest aguaje palm. And others have pursued careers such as teachers, carpenters, and ecotourism guides. Most however are still very familiar with the primary forests that surround the community.

Mongabay: How have the volunteers you bring to the Tambopata River aided the Infierno peoples and vice-versa?

Paul Rosolie: Each expedition we have run has depended heavily on the help of Infierno men and women. Employed as guides, teachers, cooks, consultants, trackers, and boat drivers, they play an essential role in making expeditions feasible. But more important than their work is what they offer to the volunteers in terms of knowledge. On both sides there is a learning experience. For my friends in Infierno, seeing the interest and appreciation which visitors have for their home (the rainforest) and way of life, is an eye opening experience. They take great pride in showing volunteers the ways of the forest, skills such as how to observe animals, what fruits and nuts are edible, what vines are needed to make brooms and hats, and how to use a machete for just about everything.

For the volunteers, it’s a chance to see a very different way of life from their own. They see people who depend solely on the natural environment for their livelihoods, and yet still live comfortably. In my opinion this is a very important lesson today, when so many people live completely detached from nature.

Mongabay: You have had a number of conservation successes through working directly with the community. What are these? Do you think your work could be replicated elsewhere?

Member of the Infierno community demonstrating life in the forest; in this case how to collect thin vines which can be woven into broom and other items. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: Through working with the community on volunteer projects we have raised money that has contributed to permanently protecting a 7000 square hectare area of primary forest. Recently we have begun a new project within the Infierno community itself. By basing volunteer expeditions on Infierno territory we are supporting the community’s ambitions to pursue revenue through ecotourism. This, combined with the discovery of the floating forest ecosystem has helped convince community decision makers to abandon plans of creating several new roads into primary forest areas.

These developments mean a tremendous sigh of relief for several dozen miles of forest. Also, because having abundant wildlife is essential in appealing to tourists, I have been able to convince some farmers in the area to cease or reduce hunting of many species. Turtle eggs are now left in peace on the river banks, tapir can walk freely, peccary numbers are rising, and the killing of ‘pest’ species such as anaconda, puma and jaguar have stopped completely.

The modest success I have had so far is reassuring, but it is a teardrop in the ocean. Even in the community itself there are still many people to reach. Just last June a puma was shot on Infierno boundaries because a farmer found it inspecting his chickens. But seeing how quickly people change is very encouraging: people want to save their way of life.

This progress can very easily be replicated – but we need more passionate conservationists to spread the word on the ground. I hope that our volunteer trips will help to create some of those.

Mongabay: You have noted that the Infiernos know everything about the forest, but little about snakes, why do you think this is?

Paul Rosolie demonstrating a venomous coral snake. Photo by Gowri Varanashi.

Paul Rosolie: Good question! I suspect the reason is twofold. People living on the rivers don’t eat snakes, nor do they benefit from them directly. Compared with other forest species which they have grown up tracking, eating, studying, or owning as pets, contact with snakes is minimal. Subsequently their snake identification skills have never been developed (even with a field guide and years of experience, I sometimes find snake identification to be difficult). This unfamiliarity combined with the stories passed around of snake bite deaths makes their phobia appear more logical.

For this reason I do my best to educate people about snakes. I do this by handling the non-venomous ones freely, and exhibiting their harmlessness. Sometimes for a larger crowd, getting voluntarily bitten is a great way to show off their benign nature. Although it scares everyone half to death, it pretty much guarantees they will remember at least that one species is harmless forever.

Mongabay: How has the work you’ve done changed the locals’ opinions regarding anacondas?

Paul Rosolie: They used to shoot them. Before I began working with anacondas all I heard were horror stories—tall tales of people who had been eaten. Anacondas were greatly feared. Today it is a constant contest to see who can find the biggest one. Today everyone in the community that I know wants to see pictures of the latest sighting; old women, children, everyone. Now when JJ, his brothers, and I go out into the bush on what used to be hunting expeditions, we are mostly searching for anacondas to measure and document.

And yet, many people are still un-informed and some still kill anacondas. This May/June while with the volunteer groups, JJ and I are planning to have an event for the community which should help us reach a lot more people. We are planning to capture a large female from the wild for a day, and use her for education. We will be giving a talk about the fact and fiction of anacondas, and inviting the people (especially children) to come and get up close to one. From what we have seen so far, this could help a lot in improving people’s image of them. Because once they calm down, anacondas are actually sweethearts.

CONSERVATION IN THE TAMBOPATA

Mongabay: What are the threats to the Tambopata River region? What are some of its threatened species?

A rare river-level view of a macaw colpa. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: Habitat destruction from development, logging, oil leases, hunting, and mercury poisoning from gold prospectors all threaten the region. Although it is one of the most intact forests on earth, the Tambopata area has been stripped almost completely of mahogany. Giant otters, black caiman and macaws are among the most severely threatened fauna. However in remote areas where humans are absent, pockets of stable populations exist.

Mongabay: How do your volunteer expeditions aid conservation efforts?

Paul Rosolie: The Tambopata/Madre de Dios region of Peru has some spectacularly vast national parks that are set up to protect areas of old growth, biodiversity-rich forest. But these parks are of little meaning if the people in the area do not respect them. Today many indigenous people living in cities and towns, who are no longer dependant on the jungle for survival, still enjoy bush meat as a delicacy. It is a problem with surprisingly vast implications; in Infierno and other native communities, frequent hunting expeditions target species such as tapir, peccary, deer, monkey, and tortoises. Through education and employment we try to encourage responsible and informed practices within the forest.

In the Infierno community we are directly aiding in small scale conservation by supporting Infierno’s efforts to preserve a 600 hectare (1,482 acres) of forest which was formerly used for hunting, wood cutting, and other exploitation. If it were not for the efforts of the Infierno community and Tamandua, the forest might not be standing today.

Also, through our ongoing studies of the area we are contributing to knowledge that could one day help in upgrading the Tambopata Reserve Zone to national park status.

Mongabay: If you could draw up a wish-list, what additional conservation initiatives would you like to see in the area?

Navigating the Las Piedras.Photo courtesy of Pail Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: I would like to see the Tambopata Reserve Zone upgraded to national park status. It would supplement the already tremendous Madidi and Bahuaja Sonene National parks by adding over a million acres of protected forest and provide protection to the lower Tambopata from the growing city of Puerto Maldonado. Also enforcement and education is needed to maintain the existing protected areas where logging, mercury poisoning, and hunting are rampant.

And it is not only the wildlife which is at stake, isolated and un-contacted tribes exist in this region. Unfortunately for them, loggers who bring guns, chainsaws, and foreign pathogens, frequently invade their lands. On both sides deaths have resulted from confrontations. I personally feel that armed guard stations on the boarders of such tribal lands are necessary to prohibit entry by loggers. For centuries these people have lived isolated, protected by the jungle. Today their way of life is threatened by our world – it is our responsibility to stop this.

VOLUNTEERING IN THE TAMBOPATA

Mongabay: How did Tamandua expeditions come about?

Paul Rosolie: After my initial trip to the Amazon I knew what I wanted to do with my life, and dedicated myself to learning as much as I could. I did this by spending time with JJ and other members of Infierno and learning about the forest. Also, the pictures and stories I returned with after each trip helped to inspire my friends and family to want to visit as well, and suddenly I found myself leading expeditions. From the beginning I knew that being in the jungle was where I belonged, but as time went on I learned that giving other people the chance to experience the place I loved most in the world was an incredibly rewarding process, and one that could help spread the conservation message.

Volunteers. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

The name Tamandua is a result of the time I spent caring for an orphaned baby giant anteater (which in Spanish is tamandua grande). Her mother was killed by farmers when she was only a month or two old. For five weeks I spent almost every minute with her mixing powdered milk with water and nursing her. Taking her for walks in the jungle and playing with her I learned that giant anteaters are as affectionate and intelligent as my golden retriever. Eventually she grew enough to return into the forest, and I lost a very good friend. But to this day anteaters remain one of my very favorite species.

Mongabay: What are the goals of your volunteer expeditions?

Paul Rosolie: Simply, the goal is to make people care about preserving the planet’s rainforests. Both for the people who live within them and for the people who buy products like mahogany and palm oil that are taken from them. In Peru we try to make locals see that preserving the forest can be more financially beneficial than degrading it, and maintaining village life more fruitful than destructive Western development. And I try to lead volunteers on an adventure that they will never forget – which is thankfully the one easy part. When people see fire-red macaws crossing the sky for the first time, or explore the giant buttress roots of a kapok tree, or find themselves holding a live spectacled caiman, I know that the jungle has done my work for me – they are hooked.

Mongabay: What types of volunteers are you looking for? What advice would you give a potential volunteer before they show-up?

Paul Rosolie with an orphaned giant anteater, the inspiration for the Tamandua name. Photo by Benjamin Muller.

Paul Rosolie: We like to get all types of people: young, old, seasoned adventurers and the uninitiated. While most who come are already nature lovers, even those who aren’t come away with a profound sense of awe for the jungle. We get some volunteers who are looking for a hardcore adventure that will test them, and we get others who want a peaceful experience and a chance to meditate in natures climax.

As for advice for prospective volunteers, I would warn them that this is not for the faint hearted. This is the real thing. It is a rare privilege to live, even for a short time, in the most biologically rich place on earth, and take part in its preservation. We live in the forest, drink the river’s water, and get dirty, really dirty! Many people are fearful of the Amazon before they come. But that doesn’t last long. It’s actually paradise, and on expeditions we have a ton of fun!

Mongabay: Do you have work for a volunteer who has a deep fear of snakes?

Paul Rosolie: Haha! Absolutely, I usually have to reassure people of this. In reality, the vast majority of the research and activities we do during expeditions does not involve snakes. Much of our time is spent walking transects and documenting the mammal life we encounter in the early morning, as well as logging a few bird species which are indicators of primary forest. Our mission is to study the ecosystem, so all things are taken into account. We focus mainly on mammals, reptiles, birds, amphibians, and even butterflies and insects. Also, on a number of occasions we have had injured or orphaned wildlife come our way, volunteers can help with this as well. In the past, volunteers have helped rehabilitate and/or rescue species such as toucan, tapir, giant anteater, bats, snakes, and a number of giant yellow-footed tortoises.

Mongabay: If someone isn’t able to volunteer are there other ways they can help your conservation efforts?

Volunteers enjoying their first look at a wild caiman. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: Yes. There are plenty of people who volunteer at home. Our website, blog, posters and other advertising is all done by volunteers. Volunteer recruiters can help us in a big way by helping us advertise, and recruit, and help to educate and inform prospective field volunteers.

Mongabay: You’ve already achieved a number of conservation successes: something most students your age only dream of. What advice would you give a young person who is also interested in pursuing grassroots conservation and a truly adventurous life?

Paul Rosolie: It’s easier than you might think. Make some good contacts; read. Check out your local conservation issues, or buy some plane tickets to somewhere. Ask to assist on a research project, volunteer with an organization, or just call me up! The world is an exciting and beautiful place with a lot of issues, problems, people and wildlife that need your help. JUST GET OUT THERE!

Mongabay: What plans do you have for the future?

Paul Rosolie: I really want to stay involved in education and continue to run volunteer expeditions, as well as continue to explore deeper and more remote areas of rainforest. I will most likely continue on to pursue a masters as well as Ph.D. Making a documentary about the region and the threats facing its wildlife and indigenous cultures is a major dream which I am currently trying to make a reality – there are a lot of issues in this region people simply don’t know about. And if this region is going to have a chance at surviving people need to see what the story on the ground is. Also on my list is someday working on a giant anteater telemetry project. There are many questions I have about their behavior inside the forest and working with them on a focused level would be incredible.

Information about Rosolie’s expeditions: Tamandua Rainforest Expeditions.

More information about expeditions as well as the floating forest and anacondas: Tamandua Expeditions Blog.

Expedition leaders Paul Rosolie and Juan Julio Duran with a female anaconda. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

A rare species of praying mantis. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Frequent night walks allow volunteers to gain hands-on experience in a rarely seen world. Amazon swamps hold an incredible diversity of nocturnal life including frogs, caiman, fish, insects, and snakes. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

The rare and beautiful Amazon Leaf frog on a volunteer’s finger. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Black Spider Monkey, Rio Las Piedras. Photo by Samuel B. Hannah.

Toucans eating palm fruit. Photo by Sammuel Hannah.

Paul Rosolie under a makeshift shelter constructed while on a four day solo expeditoin in the forest, part of Infierno jungle training. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

Sunset over the Las Piedras River. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Related articles

U.S. and Brazil sign deforestation agreement

(03/07/2010) Brazil and the United States have signed an agreement to worth together to reduce deforestation as part of an effort to slow climate change.

Guyana bans gold mining in the ‘Land of the Giants’

(03/01/2010) Guyana has banned gold dredging in the Rewa Head region of the South American country after pressure from Amerindian communities in the area. A recent expedition to Rewa Head turned up unspoiled wilderness and mind-boggling biodiversity. The researchers, in just six weeks, stumbled on the world’s largest snake (anaconda), spider (the aptly named goliath bird-eating spider), armadillo (the giant armadillo), anteater (the giant anteater), and otter (the giant otter), leading them to dub the area ‘the Land of the Giants’. “During our brief survey we had encounters with wildlife that tropical biologists can spend years in the field waiting for. On a single day we had two tapirs paddle alongside our boat, we were swooped on by a crested eagle and then later charged by a group of giant otters.”

Under siege: oil and gas concessions cover 41 percent of the Peruvian Amazon

(02/16/2010) A new study in the Environmental Research Letter finds that the Peruvian Amazon is being overrun by the oil and gas industries. According to the study 41 percent of the Peruvian Amazon is currently covered by 52 separate oil and gas concessions, nearly six times as much land as was covered in 2003. “We found that more of the Peruvian Amazon has recently been leased to oil and gas companies than at any other time on record,” explained co-author Dr. Matt Finer of the Washington DC-based Save America’s Forests in a press release. The concessions even surpass the oil boom in the region during the 1970s and 80s, which resulted in extensive environmental damage.

Illegal logging rampant in Peru

(02/15/2010) A survey of 78 forestry concessions in Peru found that 46 (59 percent) were in breach of their concession contracts, reports the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO).

Amazon rainforest will bear cost of biofuel policies in Brazil

(02/08/2010) Business-as-usual agricultural expansion to meet biofuel production targets for 2020 will take a heavy toll on Brazil’s Amazon rainforest in coming years, undermining the potential emissions savings of transitioning from fossil fuels to biofuels, warns a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The research suggests that intensification of cattle ranching, combined with efforts to promote high-yielding oil crops like oil palm could lessen forecast greenhouse gas emissions from indirect land use in the region.

Photos: park in Ecuador likely contains world’s highest biodiversity, but threatened by oil

(01/19/2010) In the midst of a seesaw political battle to save Yasuni National Park from oil developers, scientists have announced that this park in Ecuador houses more species than anywhere else in South America—and maybe the world. “Yasuní is at the center of a small zone where South America’s amphibians, birds, mammals, and vascular plants all reach maximum diversity,” Dr. Clinton Jenkins of the University of Maryland said in a press release. “We dubbed this area the ‘quadruple richness center.’”

Rainforest conservation: a year in review

(12/27/2009) 2009 may prove to be an important turning point for tropical forests. Lead by Brazil, which had the lowest extent of deforestation since at least the 1980s, global forest loss likely declined to its lowest level in more than a decade. Critical to the fall in deforestation was the global financial crisis, which dried up credit for forest-destroying activities and contributed to a crash in commodity prices, an underlying driver of deforestation.

The real Avatar story: indigenous people fight to save their forest homes from corporate exploitation

(12/22/2009) In James Cameron’s newest film Avatar an alien tribe on a distant planet fights to save their forest home from human invaders bent on mining the planet. The mining company has brought in ex-marines for ‘security’ and will stop at nothing, not even genocide, to secure profits for its shareholders. While Cameron’s film takes place on a planet sporting six-legged rhinos and massive flying lizards, the struggle between corporations and indigenous people is hardly science fiction.

Brazil allocates first funds under plan to save the Amazon

(12/10/2009) Brazil’s development bank BNDES has announced the first five recipients of grants under the South American country’s ambitious Amazon Fund, which aims to reduce deforestation by 70 percent over the next decade.

Changing drivers of deforestation provide new opportunities for conservation

(12/09/2009) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental lobby groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation.

Brazilian tribe owns carbon rights to Amazon rainforest land

(12/09/2009) A rainforest tribe fighting to save their territory from loggers owns the carbon-trading rights to their land, according to a legal opinion released today by Baker & McKenzie, one of the world’s largest law firms. The opinion, which was commissioned by Forest Trends, a Washington, D.C.-based forest conservation group, could boost the efforts of indigenous groups seeking compensation for preserving forest on their lands, effectively paving the way for large-scale indigenous-led conservation of the Amazon rainforest. Indigenous people control more than a quarter of the Brazilian Amazon.

Brazil could halt Amazon deforestation within a decade

(12/03/2009) Funds generated under a U.S. cap-and-trade or a broader U.N.-supported scheme to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and degradation (“REDD”) could play a critical role in bringing deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon to a halt, reports a team writing in the journal Science. But the window of opportunity is short — Brazil has a two to three year window to take actions that would end Amazon deforestation within a decade.

Guyana expedition finds biodiversity trove in area slated for oil and gas development, an interview with Robert Pickles

(11/29/2009) An expedition deep into Guyana’s rainforest interior to find the endangered giant river otter—and collect their scat for genetic analysis—uncovered much more than even this endangered charismatic species. “Visiting the Rewa Head felt like we were walking in the footsteps of Wallace and Bates, seeing South America with its natural density of wild animals as it would have appeared 150 years ago,” expedition member Robert Pickles said to Mongabay.com.

How rainforest shamans treat disease

(11/10/2009) Ethnobotanists, people who study the relationship between plants and people, have long documented the extensive use of medicinal plants by indigenous shamans in places around the world, including the Amazon. But few have reported on the actual process by which traditional healers diagnose and treat disease. A new paper, published in the Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, moves beyond the cataloging of plant use to examine the diseases and conditions treated in two indigenous villages deep in the rainforests of Suriname. The research, which based on data on more than 20,000 patient visits to traditional clinics over a four-year period, finds that shamans in the Trio tribe have a complex understanding of disease concepts, one that is comparable to Western medical science. Trio medicine men recognize at least 75 distinct disease conditions—ranging from common ailments like fever [këike] to specific and rare medical conditions like Bell’s palsy [ehpijanejan] and distinguish between old (endemic) and new (introduced since contact with the outside world) illnesses. In an interview with mongabay.com, Lead author Christopher Herndon, currently a reproductive medicine physician at the University of California, San Francisco, says the findings are a testament to the under-appreciated healing prowess of indigenous shaman.