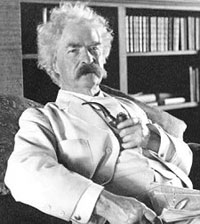

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835-1910)

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835-1910)

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was a famous and popular American humorist, writer and lecturer.

At his peak, he was probably the most popular American celebrity of his time. William Faulkner wrote he was “the first truly American writer, and all of us since are his heirs.” Clemens maintained that the name “Mark Twain” came from his years on the riverboat, where two fathoms (12 ft or 3.7 m), or “safe water”, was marked by calling “mark twain”. But it is often thought that the name actually came from his wilder days in the West, where he would buy two drinks and tell the bartender to “mark twain” on his tab. The true origin is unknown. In addition to Mark Twain, Clemens used the pseudonym “Sieur Louis de Conte” for his fictionalized biography of Joan of Arc (1896).

Early life

Sam Clemens was born November 30, 1835 in Florida, Missouri, the third of four surviving children of John and Jane Clemens.

While he was still a baby, the family moved to the river town of Hannibal, Missouri, hoping their fortunes would improve there. It was this town and its inhabitants that the author Mark Twain later put to such imaginative use in his most famous works, especially The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876).

Clemens’s father died in 1847, leaving many debts. The oldest son, Orion, soon began publishing a newspaper and Sam began contributing to it as a journeyman printer and occasional writer. Some of the liveliest and most controversial stories in Orion’s paper came from the pen of his younger brotherusually when Orion was out of town. Clemens also traveled to St. Louis and New York City to earn a living as a printer.

But the lure of the Mississippi eventually drew Clemens to a career as a steamboat pilot, a profession he later claimed would have held him to the end of his days, recounting his experiences in his book Life on the Mississippi (1883). But the Civil War put an end to commercial steamboat traffic in 1861, and Clemens had to look for a new job.

After a brief stint with a local militiaan experience he recounted in his short story, “The Private History of a Campaign That Failed” (1885) he escaped further contact with the war by going west in July 1861 with Orion, who had been appointed secretary to the territorial governor of Nevada. The two traveled for two weeks across the Plains by stagecoach to the silver-mining town of Virginia City, Nevada.

Roughing it Out West

Twain’s experiences out West formed him as a writer and became the basis of his second book, Roughing It. In Nevada, Sam Clemens became a miner, hoping to strike it rich digging up silver in the Comstock Lode and staying for long periods in camp with his fellow prospectorsanother mode of living that he later put to literary use. Failing as a miner, he fell into newspaper work in Virginia City for the Territorial Enterprise, where he adapted the pen name “Mark Twain” for the first time. In 1864, he moved down to San Francisco and wrote for several papers there.

In 1865, Twain had his first literary success. At the behest of humorist Artemus Ward (whom he had met and befriended in Virginia City during Ward’s lecture tour of 1863), he submitted a humorous short story for a collection Ward was publishing. The story arrived too late for that book, but the publisher passed it to the Saturday Press. That story, originally entitled “Jim Smiley and his Jumping Frog” but now better known as “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” was reprinted nationwide, and called by Atlantic Monthly editor James Russell Lowell “the finest piece of humorous literature yet produced in America.”

In the spring of 1866 he was commissioned by the Sacramento Union newspaper to travel to the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii) to write a series of letters reporting on his journey there. On his return to San Francisco, the success of the letters and the personal encouragement of Colonel John McComb (publisher of San Francisco’s Alta California newspaper) led him to try his hand at the lecture circuit, renting the Academy of Music and charging a dollar a head admission. “Doors open at 7 o’clock,” Twain wrote on the advertising poster. “The trouble to begin at 8 o’clock.”

The first lecture was a wild success, and soon Twain was travelling up and down the state, lecturing and entertaining packed houses.

First book

But it was another trip that established his fame as an author. Twain convinced Col. McComb of the Alta California to pay for Twain’s passage aboard the steam packet Quaker City on an American excursion to Europe and the Middle East. The resulting letters Twain produced for the newspaper reporting on the trip formed the basis of his first book, The Innocents Abroad, a large and humorous travelogue that pointedly failed to worship Old World arts and conventions. Sold by subscription, the book became hugely popular and put its author in a spotlight he never willingly relinquished for the rest of his life.

After the success of Innocents he married Olivia Langdon in 1870 and moved to Buffalo, New York, then to Hartford, Connecticut. During this period, he lectured often in the United States and England.

Later he wrote as an avid critic of American society. He wrote about politics with his Life on the Mississippi.

Career overview

Twain’s greatest contribution to American literature is generally considered to be the novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. As Ernest Hemingway said: “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn. . . . all American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

Also popular are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and the non-fictional Life on the Mississippi.

Twain began as a writer of light humorous verse; he ended as a grim, almost profane chronicler of the vanities, hypocrisies and acts of killing committed by mankind. At mid-career, with Huckleberry Finn, he combined rich humor, sturdy narrative and social criticism in a way almost unrivaled in world literature.

Twain was a master at rendering colloquial speech, and helped to create and popularize a distinctive American literature, built on American themes and language.

Twain had a fascination with science and scientific inquiry. Twain developed a close and lasting friendship with Nikola Tesla. They spent quite a bit of time together from time to time (in Tesla’s laboratory, among other places). A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court featured a time traveller from the America of Twain’s day who used his knowledge of science to introduce modern technology to Arthurian England. Twain also patented an improvement in adjustable and detachable straps for garments.

Twain was a major figure in the American Anti-Imperialist League, which opposed the annexation of the Philippines by the United States. He wrote “Incident in the Philippines”, posthumously published in 1924, in response to the Moro Crater Massacre, in which six hundred Moros were killed.

In recent years, there have been occasional attempts to ban Huckleberry Finn from various libraries, because Twain’s use of local color offends some people. Although Twain was against racism and imperialism far in front of public sentiment of his time, some with only superficial familiarity of his work have condemned it as racist for its accurate depiction of the language in common use in the United States in the 19th century. Expressions that were used casually and unselfconsciously then are often perceived today as racism (in present times, such racial epithets are far more visible and condemned). Twain himself would probably be amused by these attempts; in 1885, when a library in Massachusetts banned the book, he wrote to his publisher, “They have expelled Huck from their library as ‘trash suitable only for the slums’, that will sell 25,000 copies for us for sure.”

Many of Mark Twain’s works have been suppressed at times for one reason or another. 1880 saw the publication of an anonymous slim volume entitled 1601: Conversation, as it was by the Social Fireside, in the Time of the Tudors. Twain was among those rumored to be the author, but the issue was not settled until 1906, when Twain acknowledged his literary paternity of this scatological masterpiece.

Twain at least saw 1601 published during his lifetime. Twain wrote an anti-war article entitled The War Prayer during the Spanish-American War. It was submitted for publication, but on March 22, 1905, Harper’s Bazaar rejected it as “not quite suited to a woman’s magazine.” Eight days later, Twain wrote to his friend Dan Beard, to whom he had read the story, “I don’t think the prayer will be published in my time. None but the dead are permitted to tell the truth.” Because he had an exclusive contract with Harper & Brothers, Mark Twain could not publish “The War Prayer” elsewhere and it remained unpublished until 1923.

In his later life Twain’s family suppressed some of his work which was especially irreverent toward conventional religion, notably Letters from the Earth, which was not published until 1942. The anti-religious The Mysterious Stranger was published in 1916.

Perhaps most controversial of all was Mark Twain’s 1879 humorous talk at the Stomach Club in Paris entitled Some Thoughts on the Science of Onanism (masturbation), which concluded with the thought “If you must gamble your lives sexually, don’t play a lone hand too much.” This talk was not published until 1943, and then only in a limited edition of fifty copies.

Later life and friendship with Henry H. Rogers

Twain’s fortunes then began to decline; in his later life, Twain was a very depressed man, but still capable. Following the erroneous publication of a premature obituary in the New York Journal, Twain famously responded: “The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated” (June 2, 1897).

He lost 3 out of 4 of his children, and his beloved wife, Olivia Langdon, before his death in 1910. He also had some very bad times with his businesses. His publishing company ended up going bankrupt, and he lost thousands of dollars on one typesetting machine that was never finished. He also lost a great deal of revenue on royalties from his books being plagiarized before he even had a chance to publish them himself.

In 1893, Twain was introduced to industrialist Henry H. Rogers, one of the principals of Standard Oil. Rogers reorganized Twain’s tangled finances, and the two became close friends for the rest of their lives. Rogers’ family became Twain’s surrogate family and he was a frequent guest at the Rogers townhouse in New York City and summer home in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. They were drinking and poker buddies. In 1907, they traveled together in Rogers’ yacht Kanawha to the Jamestown Exposition held at Sewell’s Point near Norfolk, Virginia in celebration of the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Colony. Although by this late date he was in marginal health, in April, 1909, Twain returned to Norfolk with Rogers, and was a guest speaker at the dedication dinner held for the newly completed Virginian Railway, a “Mountains to Sea” engineering marvel of the day. The construction of the new railroad had been solely financed by industrialist Rogers.

Rogers died suddenly in New York less than two months later. Twain, on his way by train from Connecticut to visit Rogers, was met with the news at Grand Central Station the same morning by his daughter. His grief-stricken reaction was widely reported. He served as one of the pall-bearers at the Rogers funeral in New York later that week. When he declined to ride the funeral train from New York on to Fairhaven, Massachusetts for the internment, he stated that he could not undertake to travel that distance among those whom he knew so well, and with whom he must of necessity join in conversation.

While Twain openly credited Rogers with saving him from financial ruin, there is also substantial evidence in their published correspondence that the close friendship in their later years was mutually beneficial, apparently softening at least somewhat the hard-driving industrialist Rogers, who had apparently earned the nickname “Hell Hound Rogers” when helping build Standard Oil earlier in his career. During the years of their friendship, Rogers helped finance the education of Helen Keller and made substantial contributions to Dr. Booker T. Washington. After Rogers’ death, it was revealed in Dr. Washington’s papers that Rogers had funded many small country schools and institutions of higher education in the South for the betterment and education of African Americans.

Twain himself died less than one year later. He wrote in 1909, “I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it.” And so he did.