Reconsidering Screen Time: Research, Reason, & Real Life – Lucie’s List

Nội Dung Chính

Reconsidering Screen Time: Research, Reason, & Real Life

“Screen time” has long been a polarizing topic among parents — people tend to get judgy, defensive, desperate, panicky as sh*t (or all of the above) on the topic. Just mention the term in a roomful of parents and you might as well fracture the space down the middle; it’s like an ideological earthquake… and everyone has something to say.

When the pandemic started — especially at the beginning — the radio waves went silent. No one talked about (let alone gave their two cents on) screen time anymore, because what was there to say? What could we say? We need it? We have no other choice? Is it really that bad?

But now, so many of the conversations we set aside have begun to echo back.

We probably don’t need to tell you that “screen time” is a loaded issue. It tends to be charged with fear, a certain morality, and a certain self-righteousness.

Well, we promise that’s not what this article is about. At all. The reality is that there is a little bit we know, a lot more (so much more) that we don’t, and then there is your family — and only you know your family and your situation.

Instead of telling you what to do, we want to fill you in on some of the background (how “screen time” came to be a “thing”), some of the existing research, and some differing perspectives (both from experts and real parents alike) on screen time. IOW, it’s meant to be a primer for YOUR decision-making, rather than a how-to, per se.

Yes, full disclosure, we’ll eventually talk about ways to manage screen time, including minimizing it (at certain times and in certain situations, at least), but at the end of day those decisions are all up to you — because as we’ll see, not all screen time is equal, and screen time itself is not implicitly bad. Not at all.

Let’s just go ahead and dive in, shall we?

A note: This is a long article, friends (there’s a lot to cover!) — and we think it’s worth the full read (obviously, hah) — but if you want to jump ahead to our notes about coming to terms with your own ideas about screen time; the tactical section (on thinking through your family’s use of screens; or our concluding thoughts, we still love you. 😉 [See below for the full table of contents.]

The Evolution of Screen Time

At the outset, “screen time” may seem like a very 21st century concern — and in some ways it is. But the reality is that older generations have harbored fears about the effects of new technologies on younger generations for like… all of history. To give a few high-profile examples:

- Thousands of years ago, it was writing (yes): it impacts memory, after all. (Just ask Socrates.)

- In the middle ages, it was books, because: information overload, hello. And not everyone should have access to all that knowledge… (#knowledgeispower)

- In the 1700s, those newspapers… they’re getting too much news out there. People need to be reading their Bibles!

- In the 1800s — what in heavens’ name are they teaching those children in schools?!

- In the 1930s, it was the radio, and cartoons. (Oh my!)

- In the 1950s: television, duh. It’s overtaking radio time, how ridiculous.

- Meet the 1960s/70s: rock music. It really has a bad influence.

Shall I go on? I’m sure you could fill in the rest of the list (and then some): computers, video games, the internet, email, smartphones…

Not the RADIO!!!

Not the RADIO!!!

My point is: throughout history, concerns about various new technologies have continued to carry *very similar themes and messages: X new technology is ruining youth; it’s negatively affecting human potential; it’s detracting from the “true” experience of childhood/adolescence/adulthood/being human. And there is generally quite a bit about “virtue” and “purity” wrapped up in there, either literally or written between the lines. (Often, there has been a religious component to these woes — as in, “X is the devil’s work” or “X is trouncing all over godliness” — but there’s also a broader purist element whereby people interpret a new technology as “defouling” in some sense — i.e., watching television taints the mind.)

Screen time is (for now) the most recent iteration of this age-old discourse.

Personally, I think this historical track record with regard to technophobia is incredibly helpful to keep in mind.

Now, let’s hone in on “screen time” as a concern for a few moments…

Technically, the first concerns about “screen time” focused on excessive television viewing — which ballooned especially in the 1980s (where are our millennials at?). In fact, in 1984 (the year before a landmark study on television viewing and obesity was released), The American Academy of Pediatrics issued its first statement about media use and consumption, based on mounting evidence that children were spending more time in front of the television (~25 hours/week) than they were in school.

photo @theatlantic.com

photo @theatlantic.com

At that point, there were two predominant categories of concern: physical health (namely, sedentary lifestyle and the risk of obesity), and the potentially damaging effects of actual content (namely, violence/aggression, sex & drugs, etc.).

Early on, researchers began documenting associations between time spent watching TV and childhood obesity. In the 1980s, scientists found that there was actually a dose-response relationship, meaning that the more a child watched television, the more likely they were to be obese (even when controlling for other factors, such as race, household income, etc.). On account of this finding, they labeled television a causal association, implying that television could actually cause obesity.

Over the next decades, this association held up across studies. Even today, researchers say it’s a very well established link.

But we could challenge the labeling, I think. That’s because the TV itself doesn’t actually cause obesity. We could say that some of the behaviors/preferences associated with watching television might contribute (sedentary time, targeted junk food advertising, mindless eating in front of the television, etc.) — but we also have a much more nuanced perspective on obesity than we used to, and know that far more than “calories in, calories out” plays into that.

In the 1990s, the AAP’s guidance on “television” mushroomed to “media use.” Up until 2011, the organization urged parents to watch television together with their children, to choose what they watched carefully, and to keep children under two away from television altogether if possible, with the rationale that watching TV had no discernible merits among young children.

Current guidelines for screen time and young children differ depending on which organization you ask:

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has (sort of famously) remained very conservative on screen time. It advises that children 2-5 years old limit screen time to 1 hour daily, that children <2 only use video chatting, and that all children avoid screen time during meals and one hour before bedtime.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that babies (under 1) not be exposed to electronic screens at all, and that children 2-4 years old have no more than one hour of sedentary screen time daily. (Note the key word here: sedentary. We’ll talk about this important distinction in a bit.)

As we all continue contemplate what our ongoing transition toward “the end of the pandemic” looks like, the question of screen time has (re)surfaced for many of us. And in thinking about the last couple of decades, I think there are two major changes in our consumption of and relationship to screens/media that are worth noting:

1. Screen media has proliferated — greatly.

As we all know, screens have crept into every nook and cranny of our lives. They’re in public spaces like airports, restaurants, streets and stores; they’re lining the highways, slapped in waiting rooms, built into our cars, stashed in our bags and our kids’ backpacks, at our tables… they’re in our back pockets and on our wrists.

They’re everywhere, and they’re here to stay.

This ubiquity is a far cry from when many of us were growing up and the only screens of concern were the television or maybe a video game console (okay, and perhaps a shared old-school computer monitor for the whole family). Shoot, remember landlines? And answering machines?! Gawd, those were the days… Sigh.

The concept of “screen time” has become increasingly impossible to quantify or define (more on this in a bit) — and that’s partly because of our widespread and increasing reliance on screens across every aspect of our lives. We use our devices to talk and text with family and friends, bank and pay bills, schedule and review doctor’s appointments, look up directions, check out restaurant menus and reviews, find recipes, play music, order groceries, order and listen to books, shop… the list goes on.

“Screen time isn’t a thing; it’s 100 things.”

~ Florence Breslin, researcher at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research

2. Children are consuming screens at younger ages.

In previous decades, children typically started watching TV around the age of 4 (pre-K time). Today, many children are interacting with screens before they turn 6 months. This is a big difference, and it means we parents are thinking about the “issue” much sooner. The introduction of virtual/remote school over the past two years exacerbated this effect even further, with school-aged children suddenly relying on digital devices and tools they never would have been expected to utilize for hours each day.

Alright, so here we are — in the 2020s – with screens everywhere, all around us, and faced with the prospect of considering screen time for our kids earlier and earlier…

Where are things?

A caveat: there’s a whole ‘nother world of screen time “things to care about” for tweens and adolescents (social media, internet safety and security — gawd it’s going to be craaazy 😱), but for now, this article is mainly focused on the younger crowd.

The Problem(s) With Studying Screen Time

Let me be very clear about something at the outset: there is no empirical causal proof that screen time in itself does any damage to children. Are you surprised?

Huh. OK. (I was.)

The literature on “screen time” and how it affects young, school-aged, and even older children and teens is — to put it lightly — wanting. Available evidence points to some things, and shows some clear and worrisome associations, but it does not demonstrate causation — at all.

“The [screen time] literature is a wreck.”

~ Anthony Wagner, psychology chair at Stanford University

In fact, even the very best research into the effects of screen time is purely correlational, meaning that it only tells us there’s a link between screen time and X — it does not demonstrate that screen time causes X. In other words, even where we have data showing that screen time might have an impact, the best we can do is theorize about the causality.

That’s not the only problem. Almost all studies on screen time rely on self-reports from participants (or, in the case of children, parent reports). These are bound to suffer from simple human error: people make mistakes in their reporting, under-report, over-report, or misrepresent something. It’s inevitable. Most of the major studies on screen time and kids were also conducted pre-Covid — and we all know that the pandemic instigated rapid and sweeping changes with how young children interact with devices and digital media. Shoot, our preschool had Zoom meetings back in the spring of 2020…

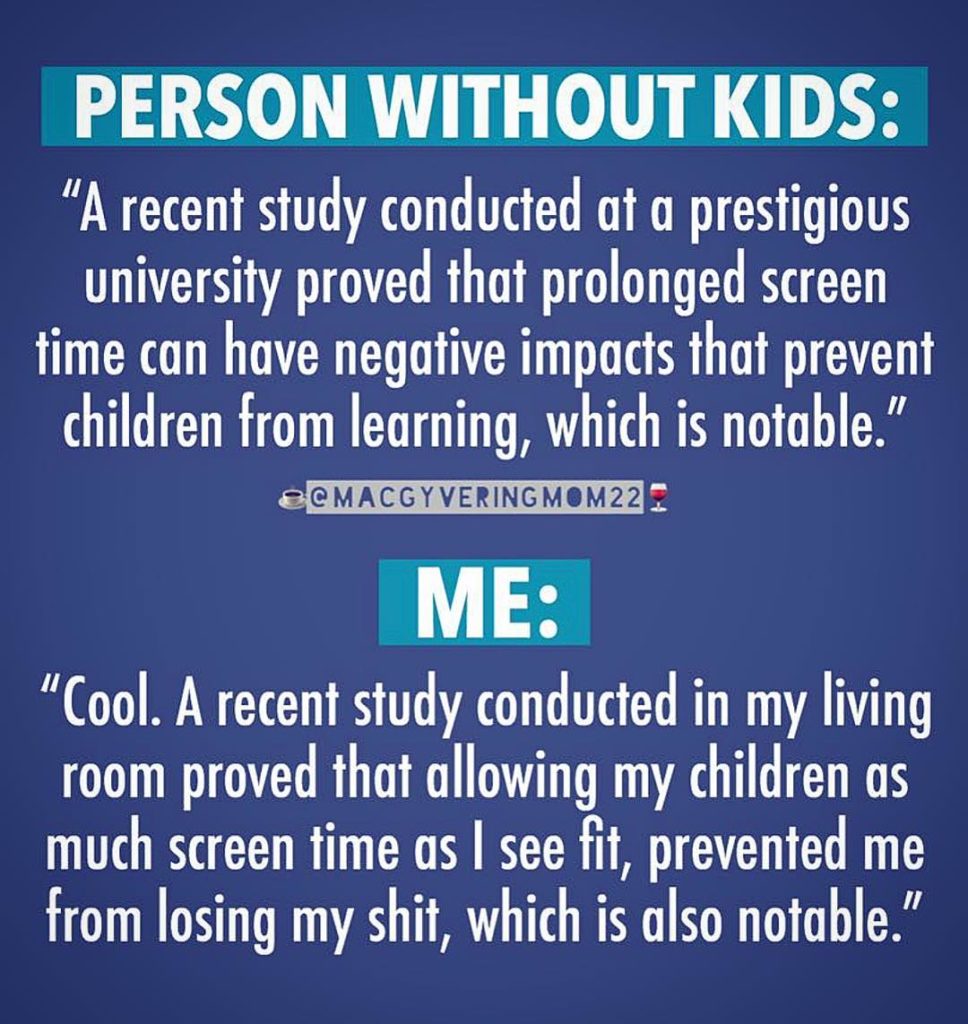

Screen time research is also subject to population bias and confounding factors. Kids who watch more television, for example, tend to live in homes that earn less money and with parents who have fewer years of education. Yes, as many of us quickly realized during the first two years of the pandemic (as many of us had to work from home and take care of children while forgoing our usual childcare support), shepherding little children through a “screen free” existence is in fact an incredibly privileged thing to be able to do. It’s effing hard.

Not only that, but virtually all of the screen time research relies on a single unit of measurement to evaluate outcomes: time.

In reality, time spent on screens is not a very useful indicator. Indeed, where “hours spent” might have been telling when it applied to one single thing (e.g. television or video games), in today’s world, time really doesn’t tell us very much.

For example, if a father reports that his child spent three hours on screens on Tuesday, who knows whether that meant FaceTiming with an aunt, watching Daniel Tiger, taking a class on Outschool, looking at nature videos online together with dad, tracing letters on an app, doing a children’s yoga sequence, or viewing pictures of a new cousin?

And are any of those things “bad”?

When it comes to thinking about screen time and children, the emerging consensus, as it were, is that time spent with a screen is far less important than what’s happening with the screen.

“We should not assume that the amount of screen time is a singular factor in overall well-being.”

~ Janis Whitlock and Philipp K Masur, JAMA Pediatrics

Generally speaking, many of our fears about screen time’s deleterious effects are unproven (or just hypotheses). In the words of the experts:

- Said a team of researchers who surveyed 20,000 parents of children ages 2-5 (2017): “Taken together, our findings suggest that there is little or no support for the theory that digital screen use, on its own, is bad for young children’s psychological wellbeing. If anything, our findings suggest the broader family context, how parents set rules about digital screen time, and if they’re actively engaged in exploring the digital world together, are more important than the raw screen time.”

- A 2019 project that evaluated survey data from caregivers of some 35,000 kids in the United States found NO negative effects associated with viewing television (up to four hours per day) and/or engaging in digital-device-based activities (for up to five hours per day). The researchers concluded: “Very few children, if any, routinely use television and device-based screens enough, on average, to show significantly lower levels of psychological functioning… Instead these findings indicate that other aspects of digital engagements, including what is on screens and how caregivers moderate their use, are far more important.”

- Editorial commentary on a meta-analysis of 30 survey studies published in JAMA Pediatrics in 2019: studies “suggest that the association between screen time and different indicators of well-being and/or functioning is often inconsistent and, at best, small.”

All of this is (somewhat) reassuring, and yet our shared concerns about screens are not entirely groundless (right??). We’ve all seen children (our own and/or others’) who appear reliant on screens for entertainment, utterly infatuated with them, or lose control when they’re turned off. And many of us are self-conscious about our own use of screens. We know how greatly we depend upon them and feel how distracting they can be… and it’s not all that unreasonable to worry (or at least wonder) about the same for our children.

Parents don’t need scientific research to tell them phones can be dangerous; they can deduce the ills from their own overuse.

~ Lauren Smiley, The Verge

So, Should We Worry?

Probably not. But maybe a little. (Shrugs.)

The way I see it, there are a few insinuations that stem from the research — and to which many of us can testify, based on personal experience — that are worth at least taking into consideration before you ask yourself the question that really matters, which is: how much do you (or can you) care? (We’ll work our way to this shortly…)

1. Devices & Attention

Young children’s brains are developing like crazy — literally tripling in size during just the first two years. Neurological synapses (connections in the brain) multiply at an unparallelled rate early in life, going from about 2,500 at birth to more than 15,000 by about age 3. It’s truly astonishing.

Point being: this is a time when a lot is happening. Young children learn SO much about the world during these early years, and presumably they carry it with them.

There are numerous studies indicating that screen time can impact that learning process. Specifically, screens may be interfering with the capacity for attentiveness — but the key caveat is that it’s really only certain types of programming that seem to have an effect.

The premise (and again this is researchers theorizing about the nature of their findings…) is that babies/toddlers who “watch” certain kinds of shows are actually being conditioned to expect a reality that does not exist.

For example: one expert in the field looked at the Baby Einstein programs and hypothesized that because they are so discombobulating — rapid and unpredictable image changes, loud music, disorienting depictions — they might actually be conditioning children’s brains to expect completely absurd and inappropriate levels of stimulation during everyday life. (Seriously — if you haven’t ever seen the program, as I hadn’t, take a peek… it’s all over the place.) Researchers have observed these effects in young children and also in animals, which, when exposed to television, frequently act in erratic, risky ways.

Scientists call this the overstimulation hypothesis, and it holds that prolonged exposure to rapid image changes during a critical period/window of brain development preconditions the mind to expect high levels of stimulation, which could lead to inattention later in life.

Comparatively, programs like Sesame Street, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, or Daniel Tiger are all carefully tailored to more closely mirror reality (or at least the pace of reality; I haven’t seen Big Bird on my block anytime of late… though you just might if you live in Brooklyn, hah!!) and present as much less disorienting than the “nonstop frenetic” kinds of shows produced by the entertainment industry, (and thus again, in theory are potentially less concerning).

For what it’s worth — and this is just our personal opinion — we think that Sesame Street looks and feels different the last several years (and some have also noticed changes since it’s more recent move to HBO a few years back). Watching the older episodes, things moved pretty darn slow… but much of the newer content and segments appear frenzied and hectic (more unpredictable changes and random songs/units that don’t seem to fit). Check out this clip from 1985, for example, compared to this new segment added around ~2010 — and try to imagine watching from the perspective of a child who’s trying to learn how the world works. There’s a big difference, right?

My takeaway from this kind of research: content matters. (Which is just another way of reiterating that screen time is not equal…)

Screen Time “Addiction”

You may have heard/read/seen/talked about screen time as an “addiction.” It’s a catchy label, and I’d be lying if I said I thought there was nothing to it, but most experts take issue with this kind of classification. They note that words matter (I agree) and warn that talking about devices and digital media under the rubric of “addiction” conveys the wrong messages — namely that screens are fearsome and all-powerful — to young people.

This rhetoric, they say, contributes to a culture of anxiety and helplessness surrounding digital devices, which is highly problematic given that our children are going to grow up using screens.

“I think one thing we have to get away from is the concept that screens are toxic… Screens are not inherently toxic. They’re neutral. It’s what we do with them that matters.”

~ Michael Rich, quoted in Mother Jones

As health professionals describe, this kind of discourse might actually be handing young children the exact language they need to remove themselves from any sort of engagement, decision-making, or responsibility regarding their own behaviors, consumption and budding identities as citizens of the digital age. IOW, if our kids hear us talking about screens as if they are inherently addictive, they may internalize the message that they have no control and/or stress about using screens (unnecessarily).

As we’ll continue to see, screens themselves are not the problem…

BTW, kids don’t see what we see:

One thing to keep in mind as you think about what role you want screens to play in your family’s life and home is the simple fact that young children don’t see what we see with screens. For example, in the so-called “popcorn study” in the 1970s, researchers displayed a huge bowl of popcorn on a TV screen in front of 3-year-olds, then asked the kids what would happen if they picked up the TV set and tipped it over.

The kids said the popcorn would fall out of the bowl. 🤣 (In other similarly-hilarious anecdotes: one 4-year-old wrote Mr. Rogers a letter asking him how he got into his television set; a child watching Sesame Street announced that he knew Big Bird wasn’t real — it was just a costume… worn by a regular bird. You’re welcome.)

Though these examples may be dated (it would interesting to see if toddlers today still fall victim to these misunderstandings), they still demonstrate that babies and toddlers interpret screens differently from tangible interactions and experiences and that, in some cases, screens can contribute to confusion because they counteract lessons babies and toddlers learn in the real world. When I think about the first times my kids used Facetime, for example, they were so confused…

A related and further note regarding screens & attention —

This isn’t a strict research finding, but it’s something that frequently crops up in different places (read: parents’ conversations, media pieces, and child psychology writings (see Aha! Parenting for one example)) and I personally believe it’s worth talking about — though I am well aware that not everyone will agree with me…

For the most part, toddlers and young children learn best from real life and real people. And it’s important for them to learn to entertain themselves, to listen, to become engaged in the world around them, to pay attention to things, or to simply wait patiently for a few minutes — on their own. (Isn’t it?) The more we replace all of these moments with screens, the more our children are able to sidestep these lessons, and the more they learn to rely on digital technologies for stimulation and engagement. The concept is: if we expect our children to learn that they are responsible for entertaining themselves — in the real world with real toys and games and people and ideas — they can and will step up to the plate. If instead we placate them with digital media at the first sign of boredom or inconveniently timed misbehavior (especially if it’s in public…), they will learn to turn to these media as a coping strategy.

Broadly speaking, this concept^ relates to so many other aspects of parenthood — sleeping, feeding/eating, etc. — that all entail our teaching (and modeling for) our children the behavior we want to see in them.

Digital Therapy

Much like with food, experts recommend avoiding screens as a source of comfort or consolation. In fact, in the long run, this tactic actually worsens things — because it does nothing to help children learn to regulate their emotions. Instead, it teaches children to rely on media for relief and to seek external sources of comfort and support. Like all things related to screen time, the research in this arena is far from perfect, but it’s a point of relatively unanimous agreement among experts, including across disciplines and perspectives.

2. Screens & Sleep

This is probably the area in which we can find the most firm footing. Studies consistently show — across device platforms, activities, and age groups — that screen media use is associated with reduced sleep quality and quantity.

I won’t belabor this point much, because the findings are so unwavering, but suffice it to say that the more time people spend on screens (babies and young children included), the worse they sleep. Exposure to screens is associated with more irregular sleep schedules, overall less sleep, and delayed onset of sleep (i.e., it takes longer to fall asleep).

Based on the evidence, sleep just might be the most important reason to think twice about screen time (not just for little children — for everyone). Aside from the fact that I firmly believe “(more) sleep” ranks very highly on virtually every parent’s list of things-I-care-most-about, children are generally not getting enough sleep.

This doesn’t necessarily mean you need to (or even can) avoid screens altogether — there are some ways to live with screens while still mitigating these effects. We’ll get to those in a bit…

3. Screens, Habits & Displacement of “Everything Else”

A lot of parenting young children is about teaching habits and setting precedents. As any parent of a toddler knows, the first time you agree to “just one more” (story at bedtime, say) is the beginning of always “one more.”

Children are creatures of habit — they thrive when they have structure, routines and boundaries, because they love to know what to expect. We make decisions everyday that are shaping our children’s habits and expectations: every time we say “no” to their helping with a task, we are teaching them that their help is unwanted or unnecessary; every time we serve a snack or meal, we are teaching them about what foods/cuisine we value and how to eat; every time we insist they clean up their toys, we are teaching them that it’s their responsibility to clean up their things (and that mom is “so mean,” lol).

The same premise holds true with screens. The parameters we establish with screens when our children are young carry forward. That’s not to say that everything is set in stone — of course not — but it’s easier to keep up with a preexisting pattern than it is to change it. (We’ll elaborate on this momentarily…)

A related concern is that screen time comes at the cost of something else — namely, displacing other important activities that benefit children: engaging with the real world, playing (outside), and physical activity. In fact, remember the WHO’s policy recommendations? They reflect exactly this belief — the organization’s advice to avoid screens from 0-2 and limit screen time to 1 hour daily is about limiting sedentary time more than device engagement. (It actually specifies “sedentary screen time,” and has similar “maximum limitations” for things like being buckled into a stroller or a car seat.)

This is a reasonable and valid concern, but it’s far from a black-and-white issue. It’s not always a choice between screen time or some wonderfully stimulating alternative. As Emily Oster wrote on five-thirty-eight in 2015, “a lot of kids and families may not use [that time] in these ways. An hour of TV may be replaced by an hour of sitting around and doing nothing, whining about being bored, or worse, being yelled at by an overtired parent who is trying to get dinner ready on a tight time frame.” Here, here.

Studies suggest that whatever theoretical negative effects screen time might exert on children’s attention/behavior, adding sources of non-screen cognitive stimulation — things like reading or singing, visiting a park or museum, playing with legos/clay/blocks, spending time outside, etc. — reduces them. Some even say that as long as you make time to read to your young child(ren), the amount of screen time they have may not matter at all.

Running with this idea, there has been a lot of judgment surrounding the notion of “using the screen as a babysitter,” but the reality is that sometimes that trade-off might be better for everyone. As a personal anecdote, whenever my kids are home for the day, I let them watch either Daniel Tiger or Sesame Street so I can exercise — and I am 100% a better parent for it. #noregrets.

*And of course, it’s inaccurate & unfair to even frame this as a decision, because often, and for so many, it’s not. Perhaps the pandemic, more than anything else, demonstrated this to us. Parents who were expected to work full-time from home with no school or child care were thrust into an impossible position. Screen time limits went out the window with everything else. And honestly, I was struck by Kiera Butler’s recent observation in Mother Jones: even before the pandemic, she says, “there was something a little out of touch about the notion that all families could fill children’s evenings with enriching games of chess and readings of Little House on the Prairie.”

Indeed, on the eve of 2020, expert advice was to avoid leaving young children alone with a screen (any screen) — but that seems straight-up ridiculous after the past two years. Anya Kamenetz, an NPR reporter and author of The Art of Screen Time, wrote a thoughtful piece in the NYT explaining that being home with her kids during the pandemic completely changed her line of thinking: “I want to take this moment to apologize,” she said, “to anyone who faced similar constraints before the pandemic and felt judged or shamed by my, or anyone’s implication that they weren’t good parents because they weren’t successfully enforcing a ‘healthy balance’ with screens, either for themselves or their children. That was a fat honking wad of privilege speaking.”

We’ll come back to this point^^ in the tactical section…

So where does this leave us??

The AAP has gotten a lot of flak for its screen time guidelines. Experts (even among the organization’s own ranks) have harangued them as lacking in evidence, overly cautious, arbitrary, and unrealistic.

And especially given that they are reliant on the precautionary principle, rather than data, we should question the AAP guidelines. Totally. We all live in this world, and our children can benefit from digital media.

“We can suspect that [screen time] may be bad, but we are still many years away from knowing, and we are nowhere near knowing what sort of exposure is safe or how much might be dangerous.”

~ Brian Resnick, Julia Belluz, & Eliza Barclay, Vox.com

And yet…

Some of our suspicions are worth following — perhaps it’s not unreasonable to think that we may want to approach screens and digital media with a greater sense of purpose.

Which brings us to our next segments: deciding whether and how much you care about your child’s relationship with screens, and some tactical tips, questions, and pieces of advice culled from… all over the place.

Step One: Decide whether or not you care (and if so, how much)

Accounting for the facts that 1) screens are everywhere and 2) we don’t have any compelling evidence that they appreciably harm our children, you could very well ask yourself whether you should care about “managing screen time” at all.

Maybe you shouldn’t!

Indeed, since the research is not condemnatory, I think this is a question we’d all benefit from asking ourselves. Honestly and with grace.

In worrying about screen time, are you just creating another “thing” for yourself? Are you forcing yourself to care about it because your neighbor or your sister or your friend does? If your “care” is coming from a place of external judgment, maybe give it a second thought. You’d have plenty of evidence to support your decision.

Or maybe you’re not in a position to even have the “option” of caring — as so many families are.

Changing Communication

Much like technophobia has come in waves, each generation sets its own priorities when it comes to socializing and communication. Penmanship, handshakes, and “letter writing” used to be of paramount importance — now… not so much. These days, being able to craft a professional email, a text message, or an IG or Twitter post have *real value. They’re skills no one would have predicted would matter.

Many of us worry that our children’s use of screens might somehow impede their ability to successfully participate and thrive in the world as adolescents and adults. But the flip side of this is that their generation is going to decide what kinds of communication and interactions to prioritize, and faculty with a screen is almost assuredly not going to harm them. (Look at how we’ve had to adjust to Zoom meetings, for instance, which have an entirely different character than in-person meetings.)

Every form of communication is a cultural construct — there’s nothing innately valuable about being able to curve your script just so, send the perfect text to a colleague, or engage with an audience on social media. These have all become skills because we’ve decided at various points of time that they matter.

Young people today are already socializing in completely different ways than we did — and we connected in totally different ways than our parents. Who knows what’s in store for our kids.

If you’re confused, you’re in good company — welcome to the club! For those who aren’t sure what to think, here is a big piece of advice from researchers:

OBSERVE your child: Every child is different. Pay attention to how your child behaves during and after using screens:

- How do they act when the screen is turned off?

- How does using/watching a screen seem to make them feel?

- What’s the general climate like surrounding screen use in your home?

- Are screens causing problems in any areas of your child’s life/daily routine?

- Have screens become all-consuming?

One expert explains that for most kids, screen time — even in copious amounts — is probably fine. But for a smaller group of more vulnerable kids, excessive screen time may be harmful.

There’s no definite description of what makes any one kid “vulnerable” — it’s *totally subjective. On our team, we joke about how some of our own kids don’t care that much about the laptop/tablet/iPhone — for whatever reason, they simply aren’t as drawn in — while our other kids (?) are so glued to screens that they literally can’t look away. Seriously, the house could be up in flames, burning to the ground around them, and they’d just keep on watching. Yes, even siblings can react to screens so differently.

It’s the same for adults, too… some people can “do” social media in a way that really serves them, but I know I have some friends who feel like the second they open the app, its like a rabbit hole they can’t climb up.

For me personally, there are a handful of compelling reasons to be mindful about screens in my home and with my children. Take them or leave them, but they are:

1. My kids’ behavior

Though one of my children has the capacity to walk away from a screen (even mid-show) with no problems, the other tends to throw tantrums whenever a show/device is turned off. This can be extremely problematic given that shows on certain platforms never END… they simply transition from one episode to the next. I’ve noticed over time that the-world-is-ending-because-this-show-is-ending tantrums are entirely avoidable… if the screen is never turned on in the first place.

Mr. Rogers ended

Mr. Rogers ended

2. My own biases/thoughts about screens.

Despite the fact that the evidence “shows no direct harm,” so to speak, my own (and my spouse’s) personal views are that we would prefer to minimize screen time in favor of “real life” activities. We aren’t on social media, we don’t have a television in our living room, and we generally endeavor to leave a more minimalist digital footprint. I’m not saying this is a superior approach, but it’s what we enjoy, what works for us, and what we want to pass on to our kids. Everyone has a different perspective on this — what’s yours?

3. The evidence on screens and sleep.

In the words of Albus Dumbledore, it’s incontrovertible: screens negatively impact sleep.

4. Setting habits, patterns, and expectations earlier is SO much easier.

Allow me to elaborate on this last point for just a minute: when our children are young, we literally have total control over their exposure to screens. This is when it’s easy! It’s always less challenging to take a more conservative tack early on and then loosen up — but going the other way is *very difficult. (This is true of virtually everything, not just screens.) One expert described it like this: “the longer you keep Pandora’s box shut, the better off you are.”

When I was a kid, my parents instituted a “no TV on weekdays” rule (and back then it was only TV — imagine!). At the time, my three younger siblings and I all thought this heinous edict was part of some sort of evil plot. We complained to no end and gave it all the WHINE our collective tribe could muster in the hopes that our parents might change their minds. (They didn’t.)

But you know what? After a while, we stopped complaining — and we never broke the rule. In fact, eventually the “rule” dissolved, and we didn’t really even know it existed. It just… was. Not watching TV during the week became a habit, and for the most part we kept it up even when we went off to college and started our own lives.

My point is: if we can help our children learn to establish the habit of moderation with screens early in their lives, that’s a valuable thing that they can bring with them as they grow up – it’s a lifelong skill. As the National Childbirth Trust (in the UK) explains, “it’s becoming more clear that children establish their activity and screen time habits early on.” To the extent that it’s feasible for us to help model and teach healthy habits, it’s never going to get easier than when they’re young. (It’s all uphill from here? LOL.)

What I’m saying is… once you offer your 3-year-old a tablet… it can be very difficult to reel that back later on.

As Dr. Dimitri Christakis, an expert in the field and the director of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute’s Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development told a reporter for the NYT: “When managing screen time among children through age 6, you can win any battle.” (It may be a battle, but you can win.)

If you take the time to think about this question — of “caring” about screen time — and decide that you really don’t, or can’t, then know that your child is fine. (Also, kudos for reading! If you stick with us, you might still find some of our user tips helpful.)

If you decide that you do or might want to think about managing your family’s screen time, then stay tuned for this last segment, on strategies for thinking that through:

Step Two: Thinking Through Screen Time

Consider Content Over Time

If you take one thing from this piece, please, please remember this:

Not all screen use is the same.

Time is honestly such a facile way to think about screen use — it simply doesn’t capture what’s happening, or how your child is acting, or how they walk away.

In the same way that we can use social media as a unifying and empowering source of community as well as an isolating or discouraging source of comparison/depression, a toddler or pre-K child can use a tablet in hundreds of different ways. Of course, everyone is going to have a different take on which kinds of uses are ideal and which are not, but there are some general points of consensus regarding ideal content for young children (see below).

“There are unprecedented opportunities for digital media to enhance learning, promote health, and strengthen families. At the same time, media use can be problematic, excessive, and harmful.”

~ JAMA Pediatrics

Of course, if you like time limits (or they work well for your family), you need not throw them out. One concept I think connects with folks is the message from Harvard scientists to “limit the dose.”

How to Pick Digital Media Content for Children

Experts point to a few considerations as you think about the best digital engagement for your child:

- SLOW, SLOW, SLOW

The best content for young children is the slowest — actually, the comically, painfully slower the programming, the better.

Sadly, much of the content aimed at young children abides by the same rules of the attention economy as for adults: it does everything possible to hold children’s attention, which means loud noises, bright colors, fast-paced visuals, and lots of surprises. In short, all the bells and whistles.

This is exactly the kind of content you want to avoid. Instead, ideal digital content for young children moves at a SLOW pace, is REPETITIVE, and leans toward PARTICIPATION — meaning that it builds in time for children to respond/react or else incorporates back-and-forth interaction with viewers.

For little children, “slower, quieter, less, is more.”

~ Alva Noe, @NPR

- Ask Yourself: Is your child benefiting from the content?

This is a highly subjective question, but that’s the point! You know your child better than anyone, so you are best poised to think about whether she’s gaining something from any particular piece of digital content.

Some items to consider in this regard:

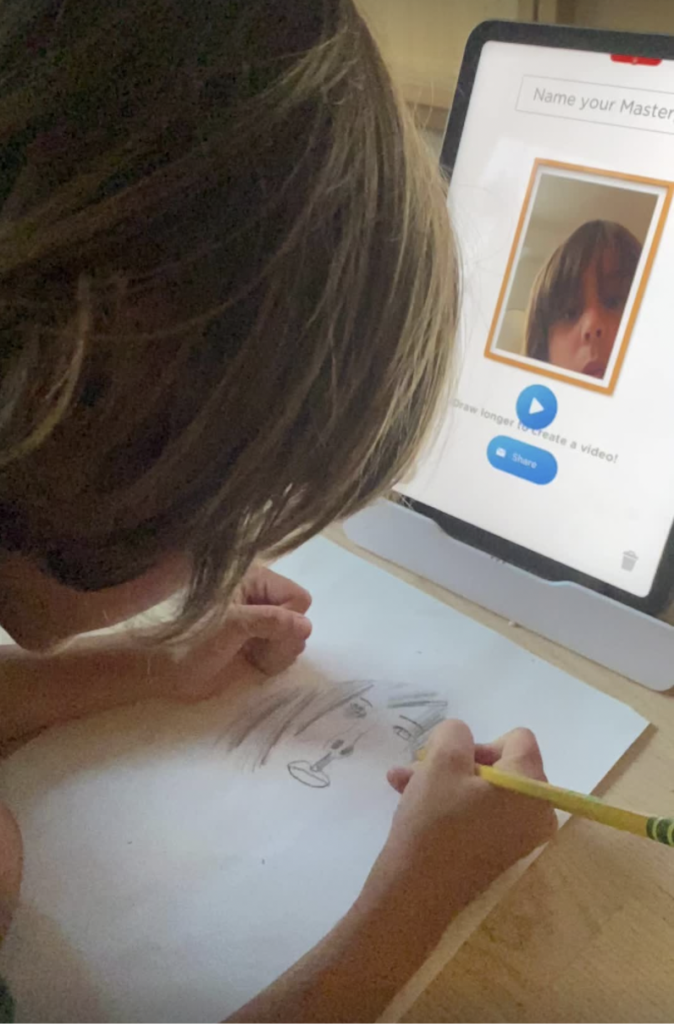

- Is the content passive or active? Generally speaking, active engagement tends to be more beneficial.

“Active” content need not be physically active — it’s not synonymous with exercise. Anything that prompts a child to think, respond, or do is active content. And it really depends on your child’s engagement. I know I’ve put on yoga videos for my kids and they’ve been so over-stimulating that they have just sat there open-mouthed gaping at them (cough, Cosmic Kids Yoga) — which is so not the point. On the flip side, I’ve also put on things like Hamilton or The Nutcracker, which are not designed to be “actively consumed,” but my kids love dancing or singing along, so they sort of are…

Dre’s STILL got it

Dre’s STILL got it

I think as adults we can recognize this distinction in our own use of devices — we all know that feeling when we’ve started the social media death scroll or the mindless surfing — and we know that those things feel very different from purposeful use of the same apps/programs.

- Is the content a source of connection or isolation?

Using screens in ways that foster human connection — however it “works” — is generally a good thing.

- Does the content appear to be recharging for your child, or draining?

This comes back to observing your child’s response to consuming screens… if the aftermath is a mess, that’s worth taking note. And if it’s just making your kids beg and whine for toys, then maybe it’s not the right show (ahem, looking at you, Ryan’s World).

- Does the content assist your child with any faculties or new skills?

- Is it helping them develop independence or autonomy?

- Does the content contain any violence? (Hint: it shouldn’t.)

A note about YouTube: there’s a lot available on YouTube, but don’t forget to use the settings to manage things for your kids. You can switch Autoplay to “off,” so that one thing doesn’t become seven, and also utilize the parental controls to limit what pops up, because otherwise totally inappropriate content may arise without warning.

- Think About It: What is the aim behind the content’s development? (Why was it produced?)

Simply considering the purpose behind the content’s creation can be incredibly telling. Was it produced for the purpose of entertaining children? Educating them? Making money? Keeping kids at the app? An easy rule of thumb is to be more wary of programs and content that stem from the entertainment industry or that were created with the express purpose of making money (again, Ryan’s World, cough).

Unfortunately, even content that markets itself as age-appropriate and/or educational is often actually “all wrong” in terms of suitability for young children.

We already mentioned the example of Baby Einstein videos, which feature numerous random scene changes and are actually quite discombobulating. In fact, much of the content we may think of as “safe” contains problematic depictions. Pay attention to how much violence crops up even in Disney films, for example (someone tallied this: EVERY animated film produced in the US from 1937-1999 contained violence). Besides the frank “hero-villain” violence that transpires in most every film, there’s also a lot of “silly” violence that can be incredibly confusing for little children — someone bopping a friend on the head, or tripping someone, for example. Not to mention all the potentially distressing content in films like The Lion King, Bambi, or even Toy Story. (Yes, “the Disney question” opens up a whole can of worms…)

We love our friend’s wonderful resource Common Sense Media — it’s a database for families that ranks media materials based on age-appropriateness, and it includes expert ratings and descriptions as well as parent reviews and testimonies. It covers all kinds of media, ranging from movies, shows, and games to books.

If you compare entertainment programs [insert Saturday-morning cartoon show here] to educational programs such as Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, it’s easy to see the differences in pacing and intent.

Take a peel at the first several minutes of this episode (or any episode, really, hah!) of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and compare it to just the theme song/intro from Puppy Dog Pals or something like SpongeBob SquarePants, and you can begin to see and feel the differences. (This is also a great article that dives into some of the program development and effects.)

“When you look at the research, the screen matters less than what you do with it.”

~ Emily Oster @538.com

Does it need to be on?

Much of the research into screen time distinguishes between “foreground” and “background” media — and contends that background media (aka, the TV is on but no one is “actively watching”) can be detrimental. Specifically, pediatricians worry that background television may impact parent-child relationships and also be incredibly distracting.

The logical follow-up here is to simply consider whether you/your child are actively using/watching a screen — if not, perhaps consider turning it off.

What is it displacing? What would your child/you be doing instead?

This is a question we all need to approach with a sense of kindness — and honesty. Generally speaking, researchers and health professionals stress that “too much” screen time (however you define it) is more problematic for what it displaces than the screen time itself. (Recall that this is the basis of the WHO’s policy, which stresses that screen time be limited specifically for being sedentary, and for disrupting sleep.)

If using a screen is detracting from your child’s play time, outdoor time, reading/music/art/whatever time, or time otherwise spent with you, family, or friends, perhaps it’s worth reconsidering.

And yet, even if we all collectively decided to agree that an hour spent playing or reading would be better than an hour of screen time, this is REAL LIFE, people. Sometimes, that hour is not “better spent” — and sometimes, everyone benefits from “using the screen as a babysitter.” (And again, refer back to your answers to the question of “how/is my child benefitting?” Maybe that iPad painting program with the animals is indeed time “better spent” than complaining about when snack time is.)

This question is something to think about, but don’t put pressure on yourself — we can’t do it all, all the time, parents…

Can you engage, too?

According to the AAP, the “chief factor that facilitates toddlers’ learning from commercial media (starting around 15 months of age) is parents watching with them and reteaching the content.”

Thus, one way to ensure screen time is “okay” is simply to watch/play/listen with your child — and if you can, that’s great!

If you’re doing something with your kid on/with a screen, don’t worry about the screen. The fact that you’re doing something together is great.

But co-viewing is not the only way — alternatively, we can (to a certain extent) reap similar benefits just by asking our kids about what they did/watched/saw/learned. The mere process of repeating what they did and explaining it to you helps them process the activity/show and also brings you into a place of communication about it.

Since realistically, most of us aren’t regularly engaging with our kids when they are using screens 🙋🏻♀️, this is a great workaround.

Build in Time for Non-Screen Things

An alternative approach to setting time limits for screens is to create mandatory time periods for non-screen things — IOW, instead of cutting out screen time, try setting aside certain times during which screens can’t be used. Since some of the valid concerns about screen time stem from what screens are displacing (namely, the “real world”… and oh boy could we go down a philosophical rabbit hole on this one…) — this strategy makes so much sense to me.

Pro-Tip: Keep a running list of non-screen activities somewhere in your home so that your family always has some ideas to draw from. If your children are old enough, invite them to contribute suggestions!

Another option? Decide on screen-free “zones” or rooms in your home — bedrooms are an obvious choice here, but you might also decide that the play room, dining room, or living room are wonderful places to keep screen free. (If your child is of the age where they’re assigned homework, that’s another time/arena to keep free of any screens that aren’t needed to complete their work.)

**The best research, health care providers, and scientists all agree that avoiding screen time during meals and one hour before bedtime is best practice, because screens can interfere with a child’s learning to eat and their sleep quality and duration.

Use The Nudge Factor

Social psychologists have demonstrated that very simple adjustments can play a huge role in decision-making and habit formation. By making certain undesirable behaviors less convenient (i.e., having to make a separate trip to the store to buy the ice cream you want to eat; not saving your credit card on your computer so you have to type in the number every time you make a purchase) or by making desirable behaviors more convenient (i.e., preparing your nutritious lunch the night before; enroll in automatic payroll deductions to save for retirement), you can drastically influence behavior. (This is a fascinating psychological premise — you can read more about it in Nudge, if you’re interested.)

There are SO many ways to use the nudge factor to impact your family’s screen media use:

- Hide the television remote

- Keep tablets out of reach from children

- Keep devices/screens unplugged/turned off when not in use

- Keep your phone/device in an inconvenient location so that you aren’t constantly checking it

- Turn off notifications

- Utilize parental controls to limit inappropriate content or create time designations when certain features are disabled

- Download the Lockwork app for Android devices

Share the Plan

If you decide on certain content/timing limitations surrounding screens, share your plan with your family. In part, this is helpful for YOU, because simply articulating your framework helps to solidify it. If you’re the type who likes a written game plan, go for it. But it need not be that formal.

If you have older children — or children who are used to a certain amount of screen “freedom” that may be changing — it’s a great idea to explain things to them as well. With little kids, you may not even need to tell them anything at all — it will just… be. This is another major benefit of starting early!

Know When To Cheat

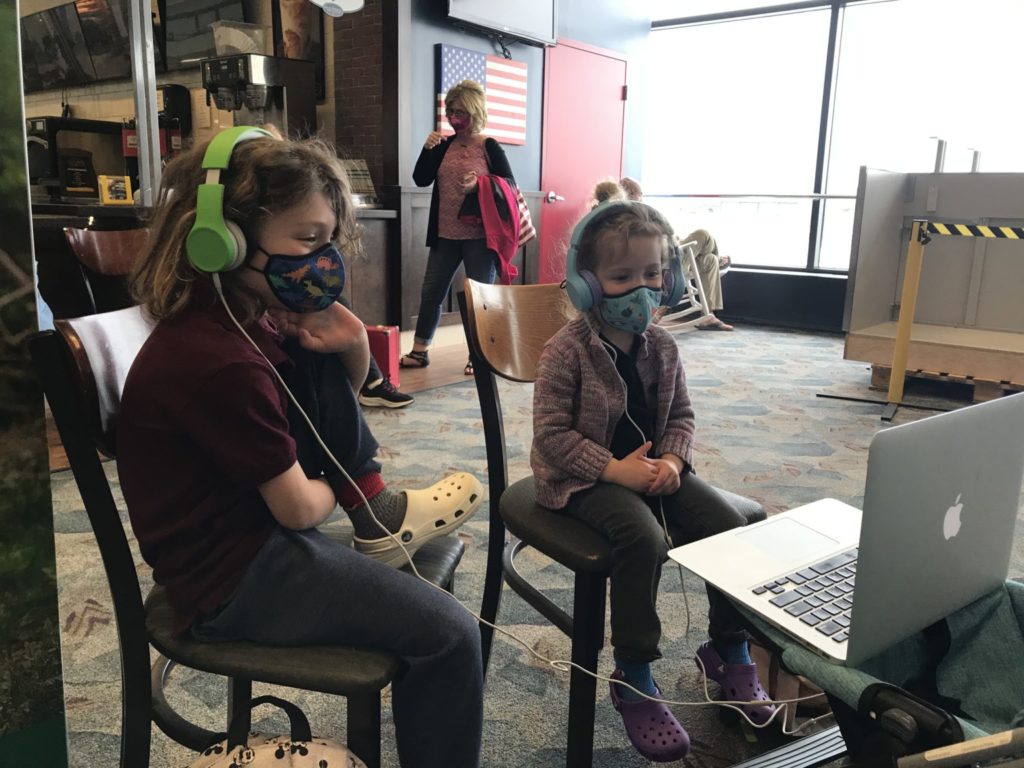

Every parent knows that there are certain times when enforcing screen time restrictions is 100% not necessary. The classic example here is “all things travel,” but there are so many other times when it might just make sense for you to be okay with loosening the reins. I have friends who relax their normal screen time rules on vacation, or whenever doing so helps them achieve some much-needed alone time or time with their partner or another child.

Chillin’ at the airport

Chillin’ at the airport

During “unusual circumstances” — a move, a sick child, a new baby, or a pandemic — letting go may be downright essential. Perhaps you need to meet a deadline, or it’s been a crazy day and having thirty minutes to exercise/shower/meditate/breathe would make the evening more enjoyable for everyone. Perhaps you need to make dinner, or talk to your sister about her new promotion, or whatever.

One thing I think we all learned from the pandemic is that we can’t beat ourselves up over these moments — the tradeoff is not always “family bliss” vs. the screen.

Virtually all experts agree that we can think of video chatting/FaceTime as an “exemption” from screen time altogether — studies show that these technologies can benefit kids greatly for their ability to connect them to parents and other relatives.

Be Mindful of YOUR Use

The unwelcome “advice” that no one wants to hear is that part of managing our children’s screen time is also managing (minimizing?) our own.

“If we can recognize our own hang-ups about screens, says child psychologist Michael Rich, who runs the Digital Wellness Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital, we’ll be in a much better position to help children navigate their digital lives.”

I was slightly terrorized to read Erika Christakis’s jarring sermon in The Atlantic because it hit a little too close to home for me. She’s not big on screen time for kids — “time spent on devices is time not spent actively exploring the world and relating to other human beings,” she says — but what struck me most about her piece was just how uncomfortable it made me feel.

In her scathing critique, Christakis calls out the distracted culture of parenting today: “for all the talk about children’s screen time,” she says, “surprisingly little attention is paid to screen use by parents themselves.” And (we) parents, apparently, are suffering from a plague of what technology expert Linda Stone coined “continuous partial attention”: a particular brand of inattention “that occurs when a parent is with a child but communicating through his or her nonengagement that the child is less valuable than the email.”

As Christakis writes, studies consistently show that parents are on their phones while they’re also with their kids — and our kids take notice. Imagine what your toddler thinks it means to be engaged in a conversation when she sees adults constantly checking their devices while talking to her. It’s a problem of chronic inattention/distraction. (Psychologists have a formal name for such interruptions — it’s called “technoference.”)

Put another way, our own device use frequently results in dividing our parenting attention. “We seem to have stumbled into the worst model of parenting imaginable,” Christakis writes: “always present physically, thereby blocking children’s autonomy, yet only fitfully present emotionally.” Yikes. [See also: Why (and How) to Be a Just Good Enough Parent]

Our use of devices also can cause us to miss or misinterpret emotional cues or otherwise overreact. I for one know that when I’m trying to multi-task and get something done while my kids are eating breakfast, say, I’m WAY more prone to become irritated or snappy when they need something from me — even if it’s something totally reasonable (or cute).

^The way I take it, Christakis’s point isn’t that you need to be with your kid all the time — and actually this would be beneficial for no one — but rather that when you are with your kid, but not fully (because you are also on a device), they see that.

Limiting our own use of screens is hard, not just for the pull screens have on our attention. We can now do lots of “good,” productive things on our devices — things that used to be discrete, separate activities, like book travel, bank, find a plumber, order food, read a book, heck, write a book. For all these reasons and more — including the fact that for many of us, our work demands the use of screens — it’s SO challenging to step away. And honestly, because of everything we can do on our screens, it’s not necessarily as simple as “stepping away” anymore.

But there’s also something incredibly refreshing when you can unplug.

Now, the fact that screens divide our attention makes me terribly uncomfortable (precisely because I fall victim to this on the regular) — yet at the same time I think it’s worth noting that screens are hardly the first thing to distract parents from their children. Before there were screens, there were other distractions. (And even without screens, there are still other distractions. I can’t tell you how many times I’m also folding laundry/emptying the dishwasher/packing a lunch/wiping up counters when I’m supposedly feeding my kids breakfast…) The point: it’s not the screen that is the problem, per se, it’s the (constant) interruptions it causes.

Not to mention: we’re sending a confusing message, aren’t we, if we tow a hard line with our kids but not with ourselves. I cringe thinking about how many times I’ve told my kids “no, you can’t do that” about a screen, while I’ve literally been checking something on my phone. It makes me feel… icky.

Which brings us back full circle: we are role models for our children all the time, whether we like it or not. We know we should (air quotes, please) model desirable behavior to help them learn about table manners, gratefulness, sharing, compromising, etc. — screen use is no different.

“When children have their own digital devices, parents need to teach them the proper times and places to use them… Parents seem far more likely to complain about their kids’ inappropriate use of gadgets than they are to teach them better behaviors. Why? Because grown-ups feel helpless when confronted with digital devices. But the truth is, if your kids don’t know when to stop, it’s your fault. You haven’t made the etiquette of a connected world clear to them.”

~ tough love from Jordan Shapiro, author of The New Childhood: Raising Kids to Thrive in a Connected World

Perhaps, at the end of the day, our focus on “screen time for kids” is entirely misplaced — “it’s easier to focus our anxieties on our children’s screen time than to pack up our own devices,” isn’t it?

Conclusion

Fellow parents, let me posit something: we don’t have to take sides in any specific “screen time debate.” Instead, it’s possible to see the value in digital tools while also believing that responsible use “exists” — not unlike environmentalism, or dietary decisions.

Young children are using screens — and expected to, at that — earlier and earlier and more and more often. Both in ways that serve them and in some ways that maybe don’t. If we don’t show them how to use screens in responsible, moderate ways that support them and their health, as mentors, who else will?

We know that there is little direct evidence in support of the idea that screens are directly harming our children’s development, but we also know from personal experience the ways in which screens can be problematic (for ourselves and our children). It’s up to us to decide what kind of example we want to set, and there’s no one right answer. I’m not on social media — and I love staying away from it — but for others it’s an incredible source of community, fun, and support. Neither choice is right or wrong. It’s just what serves us.

Some parents may decide that taking a more conservative tack when it comes to screen time is best for their families — and some may be more liberal. Everyone’s circumstances are different, and if the pandemic didn’t teach us that things can change on a dime, then I don’t know what else can.

Regardless of your particular approach, evidence suggests that it’s worth (re)considering your children’s content, because what children are doing or what they are watching on a screen is more important than the time they spend doing it — and keeping screens as far away from sleep times and spaces as possible, because screens have a decidedly deleterious effect on sleep. If you’re using a screen with your child, it’s bringing you together — and that’s a good thing.

Like any technology, it’s not the technology itself that has influence, but how we use it.

About the Author

![]()

![]()

Comments

Bibliography

Selected Resources

Bauerlein, Mark. The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future (or, Don’t Trust Anyone under 30). New York, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2008.

Becker, Rachel. “Why Calling Screentime ‘Digital Heroin’ Is Digital Garbage.” The Verge, August 30, 2016.

Browne, Dillon, Darcy A. Thompson, and Sheri Madigan. “Digital Media Use in Children: Clinical vs Scientific Responsibilities.” JAMA Pediatrics 174, no. 2 (February 1, 2020): 111. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4559.

Butler, Kiera. “Stop the Freakout Over Kids’ Screen Time – Mother Jones,” June 28, 2021. https://www.motherjones.com/media/2021/06/kids-screen-time-science-panic/.

Caron, Christina. “Too Much Screen Time? Here’s How to Dial Back.” The New York Times, December 12, 2019. https://parenting.nytimes.com/culture/reducing-screen-time-kids.

Chen, Brian X. “What’s the Right Age for a Child to Get a Smartphone?” The New York Times, July 20, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/21/technology/personaltech/whats-the-right-age-to-give-a-child-a-smartphone.html.

Cheung, Celeste H. M., Rachael Bedford, Irati R. Saez De Urabain, Annette Karmiloff-Smith, and Tim J. Smith. “Daily Touchscreen Use in Infants and Toddlers Is Associated with Reduced Sleep and Delayed Sleep Onset.” Scientific Reports 7 (April 13, 2017): 46104. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46104.

Christakis, Dimitri. “Media and Children.” Presented at the TEDx Rainier, December 28, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BoT7qH_uVNo.

Christakis, Erika. “The Dangers of Distracted Parenting,” August 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/07/the-dangers-of-distracted-parenting/561752/.

Collins, Lois M. “Toddler Throwing a Fit? New Study Finds a Screen Is Not the Answer.” Deseret News, May 26, 2021. https://www.deseret.com/2021/5/26/22444589/toddler-tantrums-byu-study-says-screens-bad-tool-for-emotional-regulation-screen-time-for-kids.

Committee on Public Education, American Academy of Pediatrics. “Media Education.” Pediatrics 104, no. 2 (August 1999): 341–43.

Congressional Record. “American Academy of Pediatrics Releases Task Force Statement on Children, Adolescents, and Television.” Congressional Record Daily Edition 131, no. 27 (1985): E872.

COUNCIL ON COMMUNICATIONS AND MEDIA. “Media and Young Minds.” PEDIATRICS 138, no. 5 (November 1, 2016): e20162591–e20162591. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2591.

Council on Communications and Media. “Media Use by Children Younger Than 2 Years.” PEDIATRICS 128, no. 5 (November 1, 2011): 1040–45. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1753.

Dietz, William H., and Steven L. Gortmaker. “Do We Fatten Our Children at the Television Set? Obesity and Television Viewing in Children and Adolescents.” Pediatrics 75, no. 5 (May 1985): 807–12.

Dredge, Stuart. “Six Screen-Time Studies That Changed My Parenting Approach.” Medium.Com, February 7, 2018. https://medium.com/s/little-minds-and-big-screens/six-screen-time-studies-that-changed-my-parenting-approach-68a3d32e0bc2.

Gopnik, Alison. “Is ‘Screen Time’ Dangerous for Children?” The New Yorker, November 28, 2016. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/11/28/is-screen-time-dangerous-for-children.

Gortmaker, Steven L., and Kaley Skapinsky. “Outsmarting the Smart Screens: A Parent’s Guide to the Tools That Are Here to Help.” Boston: Harvard School of Public Health, 2014. https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/84/2015/07/Outsmarting-the-Smart-Screens_Guide-for-Parents_Nov2014_V2.pdf.

Guernsey, Lisa. “How the IPad Affects Young Children, and What We Can Do About It.” Presented at the TEDx Mid-Atlantic, April 28, 2014.

———. Screen Time: How Electronic Media-from Baby Videos to Educational Software-Affects Your Young Child. New York: Basic Books, 2012. http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=894960.

———. “The Beginning of the End of the Screen Time Wars.” Slate, October 21, 2016. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2016/10/the_american_academy_of_pediatrics_new_screen_time_guidelines.html.

———. “When Baby Apps Actually Lead to Learning: The Lessons of Baby Einstein.” Slate, September 9, 2013. http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2013/09/baby_app_ftc_complaints_are_missing_the_big_picture.html.

Herbst, Peter. “Why Zero Screen Time for Babies Makes Sense.” The Jersey Journal, April 29, 2019. https://www.nj.com/hudson/2019/04/why-zero-screen-time-for-babies-makes-sense-parenting-with-pete.html.

Ito, Joi. “I Embraced Screen Time With My Daughter—and I Love It,” March 12, 2019. https://www.wired.com/story/ideas-joi-ito-screen-time-connected-parenting/.

Jargon, Julie. “For Kids, Free Time Equals Screen Time—So Parents Fight Back.” The Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2019, sec. Family & Tech. https://www.wsj.com/articles/for-kids-free-time-equals-screen-timeso-parents-fight-back-11563874202.

Kamenetz, Anya. “Forget Screen Time Rules — Lean In To Parenting Your Wired Child, Author Says,” January 15, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/01/15/679304393/forget-screen-time-rules-lean-in-to-parenting-your-wired-child.

———. “I Was a Screen–Time Expert. Then the Coronavirus Happened.” The New York Times, July 27, 2020, sec. Parenting. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/27/parenting/children-screen-time-games-phones.html.

Mack, Eric. “Screen Time May Actually Be Good For Kids, New Oxford Study Finds.” Forbes, October 22, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ericmack/2019/10/22/oxford-study-challenges-what-youve-been-told-about-screen-time-and-kids-for-years/#1aa179513bd5.

Madigan, Sheri, Dillon Browne, Nicole Racine, Camille Mori, and Suzanne Tough. “Association Between Screen Time and Children’s Performance on a Developmental Screening Test.” JAMA Pediatrics 173, no. 3 (March 1, 2019): 244. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5056.

Maniccia, D. M., K. K. Davison, S. J. Marshall, J. A. Manganello, and B. A. Dennison. “A Meta-Analysis of Interventions That Target Children’s Screen Time for Reduction.” PEDIATRICS 128, no. 1 (July 1, 2011): e193–210. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2353.

Markham, Laura. “Your Toddler or Preschooler and TV.” Aha! Parenting (blog), n.d. https://www.ahaparenting.com/Ages-stages/toddlers/toddler-preschooler-tv-computer.

McClure, Elisabeth R., Yulia E. Chentsova-Dutton, Rachel F. Barr, Steven J. Holochwost, and W. Gerrod Parrott. “‘Facetime Doesn’t Count’: Video Chat as an Exception to Media Restrictions for Infants and Toddlers.” International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction 6 (December 2015): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2016.02.002.

McDaniel, Brandon T., and Jenny S. Radesky. “Technoference: Parent Distraction With Technology and Associations With Child Behavior Problems.” Child Development 89, no. 1 (January 2018): 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12822.

Noe, Alva. “The Upshot of New Screen Time Guidelines? Spend Time With Your Kids.” NPR, November 4, 2016. http://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2016/11/04/500484900/upshot-of-new-screen-time-guidelines-spend-time-with-your-kids.

Oster, Emily. “‘Screen Time’ for Kids Is Probably Fine.” FiveThirtyEight, June 18, 2015. http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/screen-time-for-kids-is-probably-fine/.

Petrilli, Michael J. “Parenting in the IPhone Age.” Education Next, n.d. https://www.educationnext.org/parenting-in-the-iphone-age-book-review-art-of-screen-time-kaentz-be-the-parent-please-riley/.

Powell, Alvin. “Keeping an Eye on Screen Time.” Harvard Gazette. September 15, 2015. http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2015/09/keeping-an-eye-on-screen-time/.

Przybylski, Andrew K., and Netta Weinstein. “Digital Screen Time Limits and Young Children’s Psychological Well-Being: Evidence From a Population-Based Study.” Child Development 90, no. 1 (January 2019): e56–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13007.

Reeves, Byron, Thomas Robinson, and Nilam Ram. “Time for the Human Screenome Project.” Nature, January 15, 2020.

Resnick, Brian. “Have Smartphones Really Destroyed a Generation? We Don’t Know.” Vox, May 16, 2019. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2019/2/20/18210498/smartphones-tech-social-media-teens-depression-anxiety-research.

Resnick, Brian, Julia Belluz, and Eliza Barclay. “Is Our Constant Use of Digital Technologies Affecting Our Brain Health? We Asked 11 Experts.” Vox, February 26, 2019. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/11/28/18102745/cellphone-distraction-brain-health-screens-kids.

Rueb, Emily S. “W.H.O. Says Limited or No Screen Time for Children Under 5.” The New York Times, April 24, 2019, sec. Health. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/24/health/screen-time-kids.html.

Saker, Anne. “Too Much Screen Time Changes Children’s Brains, Study Finds.” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 4, 2019. https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/parenting/2019/11/04/too-much-screen-time-changes-brains-says-cincinnati-childrens-study/4156063002/.

Shapiro, Jordan. The New Childhood: Raising Kids to Thrive in a Connected World. First edition. New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2018.

———. “What You Really Need To Know About Screen Time And Your Kids.” Forbes, January 23, 2019.

Smiley, Lauren. “THE SCREEN TIME DEBATE IS PITTING PARENTS AGAINST EACH OTHER.” The Verge, March 8, 2018. https://www.theverge.com/2018/3/8/17095582/smartphone-screen-time-parenting-child-development.

Strauss, Elissa. “Why We Should Stop Calling It ‘screen Time’ to Our Kids.” CNN, November 14, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2019/11/14/health/screen-time-rename-parenting-house-wellness-strauss/index.html.

Tamana, Sukhpreet K., Victor Ezeugwu, Joyce Chikuma, Diana L. Lefebvre, Meghan B. Azad, Theo J. Moraes, Padmaja Subbarao, et al. “Screen-Time Is Associated with Inattention Problems in Preschoolers: Results from the CHILD Birth Cohort Study.” Edited by Luca Cerniglia. PLOS ONE 14, no. 4 (April 17, 2019): e0213995. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213995.

Trust), NCT (National Childbirth. “Screen Time for Babies and Toddlers: The Evidence.” NCT (National Childbirth Trust), September 17, 2019. https://www.nct.org.uk/baby-toddler/games-and-play/screen-time-for-babies-and-toddlers-evidence.

Twenge, Jean M. IGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy?: And Completely Unprepared for Adulthood: And What That Means for the Rest of Us. New York: Atria Books, 2018.

NewYork-Presbyterian. “What Does Too Much Screen Time Do to Kids’ Brains?,” August 8, 2019. https://healthmatters.nyp.org/what-does-too-much-screen-time-do-to-childrens-brains/.

Whitlock, Janis, and Philipp K. Masur. “Disentangling the Association of Screen Time With Developmental Outcomes and Well-Being: Problems, Challenges, and Opportunities.” JAMA Pediatrics 173, no. 11 (November 1, 2019): 1021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3191.