Realizing Your Meaning: 5 Ways to Live a Meaningful Life

At some stage of our time on Earth, we might wonder about the meaning of our life.

At some stage of our time on Earth, we might wonder about the meaning of our life.

If you have ever had this thought, then take comfort that you are not alone. There is ample anecdotal evidence that people are looking for ways to live a more meaningful life.

Living a meaningful life and deciding what is meaningful are age-old questions (e.g., Marcus Aurelius wrestled with this question when he was Emperor of Rome from 161 to 180 AD).

If you are reading this article, then living a meaningful life must be of interest to you. You might be wondering what we mean by ‘meaningful,’ and whether there are any benefits to striving toward such a way of living. Are there any practical suggestions for how to achieve a meaningful life?

Here we will summarize the existing psychological research that examines this question and provide you with a starting point on your journey.

Before we get to the practical suggestions about how to live a meaningful life, we first define what ‘meaningful’ means, explore why living a meaningful life is worthwhile, and detail the benefits that are associated with this type of experience.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free. These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations, and goals and will give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students, or employees.

Nội Dung Chính

The Big Questions: How to Find Meaning in Life

The question of finding meaning in life has its roots in two fields: philosophy and psychology.

The philosophical question is aimed at understanding the meaning of life in general, as well as our role in that meaning. For the purposes of this article, we’re putting the philosophical perspective on this issue to the side. As psychologists, we can’t contribute to this answer.

However, the second variation of this question – how we find meaning in life – is psychological and of more interest to us.

A Psychological Take

At some stage in our lives, we will be confronted with variations of the following questions:

At some stage in our lives, we will be confronted with variations of the following questions:

- Why am I doing this?

- Do I want to do this?

- What do I want to do?

These questions are also repackaged in popular psychology and leadership self-help books, such as Find Your Why (Sinek, Mead, & Docker, 2017) and How to Find Your Passion and Purpose (Gaisford, 2017).

Observant readers might comment that these are questions typically asked about our vocations or professional activities. However, people who are unemployed or employed part time also ask questions such as these and seek a meaningful life. These questions are easily repurposed for other spheres of our lives.

Before we can answer the question of how to find meaning, we first need to consider what is meant by ‘meaning.’

Psychological researchers conduct research and measure psychological constructs such as happiness, depression, and intelligence. However, constructs first need to be defined before they can be measured.

Although ‘meaningfulness’ is often confounded with other constructs such as purpose, coherence, and happiness, some researchers argue that these constructs are not interchangeable, but instead form a complex relationship and exist separately.

For example, Steger, Frazier, Oishi, and Kaler (2006) posit that meaning consists of two separate dimensions: coherence and purpose. Coherence refers to how we understand our life, whereas purpose relates to the goals that we have for our life.

Reker and Wong (1988) argue that meaningfulness is better explained and understood using a three-dimensional model consisting of coherence, purpose, and a third construct: significance. Significance refers to the sense that our life is worth living and that life has inherent value. Together, these three constructs contribute to a sense of meaningfulness.

In some research, coherence, purpose, and significance have been reframed as motivational and cognitive processes. Specifically, Heintzelman and King (2014) suggest a model with three components: goal direction, mattering, and one’s life making sense.

Goal direction and mattering are both motivational components and synonymous with purpose and significance, respectively. The third component – one’s life making sense – is a cognitive component, akin to significance.

Together, these three components – coherence, purpose, and significance – result in feelings of meaningfulness. Knowing that meaningfulness is derived from three distinct fields, let’s look at ways in which we can find our meaning.

Video

Finding something to live and die for – Einzelganger

5 Ways to Realize Your Meaning

How can we go about finding our meaning? First, there is no single panacea to the sense of living without meaning. Finding meaning is ultimately a personal journey. What brings me meaning might not bring you meaning. However, this doesn’t mean that the techniques used to find meaning won’t be helpful. Viktor Frankl (1959, p. 99) supported the notion that finding meaning is a unique journey when he wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning:

Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life and not a “secondary rationalization” of instinctual drives. This meaning is unique and specific in that it must and can be fulfilled by him alone; only then does it achieve a significance that will satisfy his own will to meaning.

With this mind, consider the following suggestions in your quest to find meaning:

1. Foster a passion (purpose)

Vallerand (2012) argues that either motivation or passion drives our desire and interest in activities.

Motivation is useful for activities that are considered dull (e.g., washing the dishes), whereas passion is the driving force for activities that have significance for us.

Passion can be negative or positive, however. Negative passions, referred to as obsessive passions, are maladaptive and lead to unhealthy behaviors; these types of passions should be avoided. On the other hand, positive, harmonious passions improve our behavior and lead to optimal functioning.

Vallerand (2012) found that people who had more harmonious relationships with their passions also had stronger relationships with the people who shared their passions.

2. Develop and foster social relationships (purpose, significance)

Making connections with other individuals and maintaining these relationships are reliable ways to develop a sense of meaningfulness (Heintzelman & King, 2014).

People who report fewer social connections, loneliness, and ostracism also report lower meaningfulness (Williams, 2007). Sharing your passions with a group of like-minded individuals also helps further develop harmonious passions, which, in turn, can generate a sense of meaningfulness (Vallarand, 2012) .

3. Relationships that increase your sense of belonging (significance)

Although social connections are important, not all social relationships are equal. Make sure to focus on relationships that make you feel like you ‘belong’ (Lambert et al., 2013), where you feel like you fit in with the members of that group, and where there is group identification.

Participants who were asked to think of people with whom they felt that they belonged reported higher ratings of meaningfulness compared to participants who remembered instances when they received help or support, or instances when they received positive compliments or statements of high social value (Lambert et al., 2013).

These findings also tie in with the negative impact of ostracism on the sense of meaning (Williams, 2007). If you feel like you don’t belong, then you have a lower sense of meaningfulness.

4. Monitor your mood (coherence)

Experimental laboratory studies have demonstrated a temporal relationship between positive mood and sense of meaning. Inducing a positive mood results in higher reports of meaning (for a review, see Heintzelman & King, 2014).

Managing your mood can be difficult. However, there are some techniques that you can use; for example, make time for interests and hobbies, get enough sleep, exercise regularly, eat healthily, and consider developing a mindfulness practice (e.g., through meditation).

5. Take control of your environment (coherence)

A cognitively coherent environment can boost ratings of meaningfulness (Heintzelman & King, 2014).

Heintzelman and King (2014) suggest that routines, patterns (which could refer to your behavior and the behavior of your family), time blocking, and clean environments can all contribute to an increased ability to make sense of one’s environment, which in turn can lead to an increased sense of meaningfulness.

Simple ways to induce a cognitively coherent environment would be to implement a fixed routine, schedule time for unexpected tasks (e.g., “emergencies” delivered via email), formally schedule downtime for exercise and passions, and maintain a tidy environment (in other words, your desk is not the place for all those dirty coffee mugs).

However, do not be unreasonable with your expectations of your environment. Unexpected challenges will pop up. Your child might have a meltdown, or you might drop a box of eggs on the floor, but these experiences will have less of a negative impact if you already have a sense of control over your environment.

Finding Meaning as You Age

Our life circumstances and experiences change as we age. We go through various life stages, such as parenthood and career changes, and each stage presents us with unique challenges and achievements.

Our life circumstances and experiences change as we age. We go through various life stages, such as parenthood and career changes, and each stage presents us with unique challenges and achievements.

We are also likely to experience multiple losses as we age. We may lose our parents, our partners, face layoffs, or develop an illness. The stereotypical concept of an older adult is of someone who is frail and requires care; however, older age is not synonymous with a less meaningful or valuable life.

In fact, many older adults live incredibly long, busy lives, and their positive psychological profiles act as a buttress against illness, loneliness, and depression. There is vast evidence that centenarians have very positive attitudes and psychological traits and few negative personality traits.

Centenarians are more relaxed and easygoing (Samuelsson et al., 1997), place a great deal of importance on social relationships and events (Wong et al., 2014), have a more positive life attitude in general (Wong et al., 2014), and report low anxiety (Samuelsson et al., 1997).

These positive aging traits and attitudes, coupled with the few negative traits, act as a protective buffer against depression, illness, and loneliness (Jopp, Park, Lehrfeld, & Paggi, 2016; Keyes, 2000), and contribute to the longevity of centenarians.

It is difficult to change your personality traits suddenly; however, it is possible to change your thinking patterns by working with a therapist trained in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Your therapist can help you identify and change negative patterns of thinking and behavior, and help you to adopt a positive pattern of thinking.

Centenarians greatly value their social experiences and are actively involved in social events (Wong et al., 2014).

It can be difficult for older adults to make new social connections, especially after retirement, because the ‘natural environment’ for meeting new people, such as the workplace, is removed. However, this doesn’t mean that there aren’t ways for older adults to meet new people and form new relationships.

With retirement comes more free time and possibly an opportunity to develop a new hobby or passion. And as we previously mentioned, finding a passion is one way to develop meaning. Vallerand (2012) provides an excellent summary of the role that motivation plays in developing passion and how passion leads to a meaningful life.

If you are an older adult, then perhaps this is good time in your life to start. Remember that positive (rather than negative/obsessive/maladaptive) passions are born from the positive association made with particular activities (Vallerand, 2012). These passions are activities that we find time for, that we invest in, and that we embody.

For example, if you have a passion for painting, you will carve out time to paint, experience a great deal of happiness when you complete the activity, and may embody that passion in your understanding of your identity (e.g., you may consider yourself a ‘painter’). Embodying the activity into your understanding of your self-concept is one of the first steps toward laying habits (Clear, 2018).

Harmonious passions (Vallerand, 2012) play a vital role in how we find meaning in our lives.

These positive passions are worth developing. Not only do they help us find meaning in our lives, but older adults who do have a ‘passion’ also score higher on measures of psychological wellbeing. They report higher life satisfaction, better health, more meaning in their lives, and lower anxiety and lower depression than adults without a passion (Rosseau & Vallerand, 2003, as cited in Vallerand, 2012).

To summarize, it appears that centenarians adopt a positive mindset and psychological traits and value their social relationships. These factors may contribute to a longer, more meaningful life and protect against illness and depression. Fostering interests and hobbies is another way to find meaning in your life, buttressing against negative feelings and thoughts.

So, what can you do to find meaning in your life as you age? The following list can give you some guidance:

1. Make time for friends, family, and social events

It’s easy to neglect social relationships in favor of alone time (which is also important) or work deadlines, but promoting these relationships will have a more positive impact in the long term. If you are the type of person who forgets to see friends or family, add a reminder to your calendar.

2. Start now to develop a new hobby or interest

Carve out some time for your own interest and commit to that time. If you have a partner, ask your partner to shoulder other responsibilities during that time so that you can indulge your interests.

3. Express what makes you happy

If you’re in the early stages of developing a new hobby, it might help to express what you enjoy about the hobby. Consider writing a journal entry about what you enjoyed or tell your partner/friends/family members about your new hobby.

Expressing why you enjoy the hobby helps to build and strengthen positive associations with the hobby.

4. Share your hobby

Try to find a group of like-minded individuals who enjoy the same interest that you do. If you like painting, consider joining an art class.

Or perhaps you want to learn a new language. Try to find people who are also learning this language and watch a film in that language together.

5. Aim to engage and invest in your community

Simple acts such as greeting and chatting to your neighbors, talking to the vendors at your local stores and neighborhood markets, and participating in neighborhood events will help you to develop relationships with your community members.

With time, these relationships will deepen and become more meaningful. Furthermore, recognize that as an older adult, you can offer a great deal to your community. You have lived through numerous life experiences, career/professional/vocational decisions, and family decisions. You have a wealth of knowledge that you can share with your community.

Older adults who regularly engage in their favorite pastimes and who have a healthy, positive relationship with their favorite activity have better psychological functioning.

9 Inspiring Quotes About Finding Meaning

Each of us must become impassioned, finding meaning and self-fulfillment in our own life’s journey.

Alexandra Stoddard

Life is difficult. Not just for me or other ALS patients. Life is difficult for everyone. Finding ways to make life meaningful and purposeful and rewarding, doing the activities that you love and spending time with the people that you love – I think that’s the meaning of this human experience.

Steve Gleason

For the meaning of life differs from man to man, from day to day and from hour to hour. What matters, therefore, is not the meaning of life in general but rather the specific meaning of a person’s life at a given moment.

Viktor E. Frankl

I don’t like work – no man does – but I like what is in the work – the chance to find yourself. Your own reality – for yourself not for others – what no other man can ever know. They can only see the mere show, and never can tell what it really means.

Joseph Conrad

There is something infantile in the presumption that somebody else has a responsibility to give your life meaning and point… The truly adult view, by contrast, is that our life is as meaningful, as full and as wonderful as we choose to make it.

Richard Dawkins

Old friends pass away, new friends appear. It is just like the days. An old day passes, a new day arrives. The important thing is to make it meaningful: a meaningful friend – or a meaningful day.

Dalai Lama XIV

I believe that I am not responsible for the meaningfulness or meaninglessness of life, but that I am responsible for what I do with the life I’ve got.

Hermann Hesse

It’s not how much money we make that ultimately makes us happy between nine and five. It’s whether or not our work fulfills us. Being a teacher is meaningful.

Malcolm Gladwell

My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style.

Maya Angelou

PositivePsychology.com Resources

We have different types of resources that you will find useful in helping you live a meaningful life:

1. From Our Worksheet Library

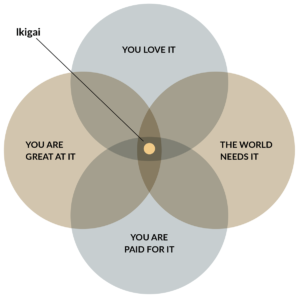

In Japanese culture, to find meaning and purpose in life is to find one’s ikigai. We have a fantastic and in-depth exercise called Identifying Your Ikigai, which takes you through a series of steps to assess and help you find your fulfilling meaning in life.

Living a life with meaning and value can make you happier, more content, more resilient through hard times, and more likely to influence the lives of others.

If you are filled with questions about what you should do with your life and what really matters, then the Uncover Your Purpose worksheet is for you. It has several tough questions, but if you can answer them honestly and comprehensively, it will shine a light on the path you are meant to follow.

2. Podcasts

The two cofounders of PositivePsychology.com offer a lighthearted podcast episode about passion, work, and money, and how they encourage others to follow their passion and live a more authentic life.

Here is a short list of other useful podcasts that tackle issues around finding meaning in one’s life:

3. Physical Meeting Groups

If you are looking for social groups that share your interests or hobbies, then consider using Meetup.com.

Meetup is a ‘social connections’ site. People create local groups for like-minded individuals, and these groups indulge in professional interests (e.g., entrepreneur support groups), physical activities (e.g., hiking), and social interests (e.g., opera lovers or book clubs).

4. 17 Meaning & Valued Living Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others discover meaning, this collection contains 17 validated meaning tools for practitioners. Use them to help others choose directions for their lives in alignment with what is truly important to them.

A Take-Home Message

Finding meaning in life is a journey that could start with something as simple as a pen and paper, deep reflection, and one of our tools mentioned above. Or your journey could start by stepping out the door and connecting with a neighbor, making a newfound friend, or starting a hobby you have wanted to explore but never got around to.

During your journey, you might that having meaning in life is not about yourself, but serving others.

Selfless service is often discovered to be the ultimate pinnacle of having a meaningful life, and many intriguing conversations with service workers, nurses, aid workers, and volunteers illustrate how they enjoy a meaningful life by serving others.

We hope that after reading this article you will also embark on this journey to find meaning in your life. We shared many different strategies you can implement when looking for that ultimate answer, and we sincerely hope that when you have found your ikigai, you will make changes to actively live that life of meaning. If some of the strategies do not work for you, try another suggestion from the list.

Most important is to find a meaning that makes sense to you and recognize that this meaning might change as you go through different stages of your life.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free.

References

- Clear, J. (2018). Atomic habits: An easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. Random House.

- Frankl, V. (1959). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

- Gaisford, C. (2017). How to find your passion and purpose: Four easy steps to discover a job you want and live the life you love (The art of living). Blue Giraffe Publishing.

- Heintzelman, S. J., & King, L. A. (2014). Life is pretty meaningful. American Psychologist, 69(6), 561–574.

- Jopp, D. S., Park, M. K. S., Lehrfeld, J., & Paggi, M. E. (2016). Physical, cognitive, social, and mental health in near-centenarians and centenarians living in New York City: Findings from the Fordham Centenarian Study. BMC Geriatrics, 16.

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2000). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychology, 62(2), 92–108.

- Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427.

- Reker, G. T., & Wong, P. T. P. (1988). Aging as an individual process: Toward a theory of personal meaning. In J. E. Birren & V. L. Bengston (Eds.), Emerging theories of aging (pp. 214–246). Springer.

- Samuelsson, S. M., Alfredson, B. B., Hagberg, B., Samuelsson, G., Nordbeck, B., Brun, A., … Risberg, J. (1997). The Swedish centenarian study: A multidisciplinary study of five consecutive cohorts at the age of 100. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 45(3), 223–253.

- Sinek, S., Mead, D., & Docker, P. (2017). Find your why: A practical guide for discovering purpose for you and your team. Portfolio.

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kahler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93.

- Vallerand, R. J. (2012). From motivation to passion: In search of the motivational processes involved in a meaningful life. Canadian Psychology/ Psychologie Canadienne, 51(1), 42–52.

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 425–452.

- Wong, W. C., Lau, H. P., Kwok, C. F., Leung, Y. M, Chan, M. Y., & Cheung, S. L. (2014). The well-being of community-dwelling near-centenarians and centenarians in Hong Kong: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 14(63), 1–8.