Orient Express to axe UK section after 41 years due to Brexit

When the Orient Express began operating in the 19th century, passports were optional – the only paperwork required by British travellers was a copy of the Thomas Cook Continental Timetable.

But Brexit and 21st-century biometric checks are killing off the romance of crossing borders for modern passengers looking for the nostalgia of the luxury train journey that inspired Agatha Christie and Hollywood.

Belmond, the company that runs today’s Venice Simplon-Orient-Express (VSOE), has decided to drop the London-to-Folkestone leg of the route because it has become too difficult to cross the border to Calais.

Until now, passengers have been able to ride in art deco carriages of the British Pullman service from Victoria station in London to Folkestone. There they board coaches to cross the Channel to meet Belmond’s continental train at Calais, then, as night falls, they dress for dinner; a compartment in one of the vintage 1929 cars costs from £3,530 to £10,100 per person, so evening dress is required, and jeans, as Hercule Poirot would expect, are banned.

The restored art deco interior of a VSOE sleeping car.

The coach transfer creates an unacceptable risk for Belmond, as there is no way for their passengers to avoid delays crossing the Channel. Travellers, including school coach parties, had to wait up to 14 hours at Dover at the beginning of the Easter holidays two weeks ago, and people also faced queues for Le Shuttle.

Things may get worse, Belmond fears, because the UK and EU are planning new biometric passport checks and extra red tape.

“We’re adjusting operations in 2024 ahead of enhanced passport and border controls,” a Belmond spokesperson said. “We want to avoid any risk of travel disruption for our guests – delays and missing train connections – and provide the highest level of service, as seamless and relaxed as possible.”

The EU is introducing a new biometric Entry/Exit System (EES), which will mean most people travelling across the Channel who do not have EU residency will need to provide fingerprints and facial recognition data when they cross the border, instead of having their passports stamped.

If the technology works smoothly, that could mean travellers over 12 years old will be able to use electronic entry gates and potentially save some time. But since even babies will need to provide biometric data, there is scepticism in the tourist industry about how the checks will work in practice. EES was due to begin this year but is now likely to come into force after the 2024 Paris Olympics.

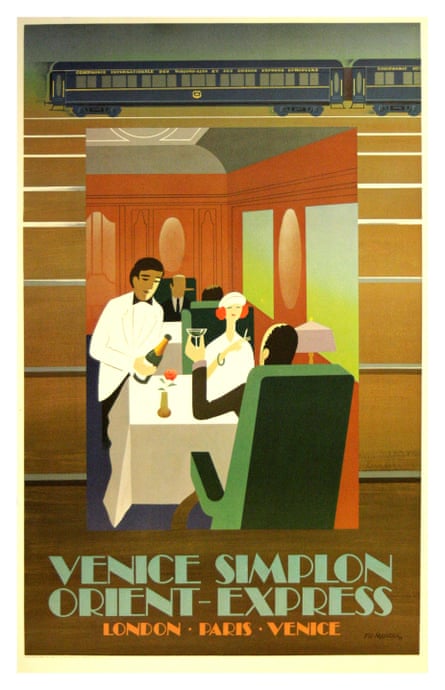

A vintage-style poster advertising the service.

Photograph: Shawshots/Alamy

And soon the EU and the UK will be making travellers submit pre-travel authorisation forms similar to the United States’ Esta scheme. British travellers will pay €7 to give European authorities personal information not on their passports – such as criminal convictions, education and parents’ first names – under Etias, the European Travel Information and Authorisation System. European travellers will provide similar details to the British government for the UK’s Electronic Travel Authorisation (Eta) programme, although Whitehall has yet to set a fee for it.

This is not great material for cosy mystery stories. “Technology has made many things easier,” said Mark Smith, founder of the train travel site The Man in Seat 61. “But the one thing that it’s made harder is crossing borders. In the old days, whatever border you’re at, there’s your passport, off you go. Suddenly everyone wants to take your fingerprints as if you’re a criminal.”

Losing the British Pullman was a “huge shame”, he said. “The British Pullman was the hors d’oeuvre – it set you up with smoked salmon and champagne on the way from London to Folkestone on the traditional boat-train route that passengers heading to the Orient Express would have used in the 1930s. Joining the continental train at Calais in time to get dressed for dinner was wonderful.”

Passengers from London will be able to take the modern high-speed Eurostar to Paris and join the VSOE there, but “it’s not the same”, he said. “It is a great shame if that part of the experience is gone.”

Not that the VSOE is entirely authentic, compared with the original service, he added. “It was a much more businesslike train than most people imagine. The real thing would not have had pianos or lounges or bars, and certainly no balcony, whatever Kenneth Branagh thinks. You would have had sleeping cars and sat in your compartment in day mode most of the time.”

The original Orient Express began service in 1883, running from Paris to Vienna, and several trains running the route south from France were given the name. The Simplon Orient Express began in April 1919 and Christie was inspired to write her novel Murder on the Orient Express after reading about the train being stuck in snow for five days. The Venice Simplon-Orient-Express was revived when James Sherwood bought some 1929 sleeping cars at auction in 1977 and began running the service from London in 1982.

Smith, a former station manager at Charing Cross, said that despite the high ticket prices, the VSOE was not elitist. “Most people are splurging on a special event – it’s a once in a lifetime experience. I wondered whether any trip could be worth three grand, or whatever it was I paid in 2003. But here I am 20 years later, married, with a mortgage, kids, two cats and a dog. Powerful magic – we’d only been going out for six months.”

Brexit has ended other train journeys as well – Eurostar’s service from St Pancras to Disneyland Paris will finish this summer.

The UK is also losing out on tourists from the rest of the world, according to Tom Jenkins, chief executive of Etoa, the European tourism association. “People are starting to drop the UK as a gateway to a European tour,” he said. “It’s not the only factor, but previously we had been the principal arrival point for people coming to Europe from America, from Japan, and anywhere else.

Albert Finney, centre, as Hercule Poirot with an all-star cast in the 1974 film version of Murder on the Orient Express.

Photograph: Studiocanal/emi/Allstar

“It was made perfectly clear in 2018 that a hard Brexit would mean UK citizens would have to have their passports checked. This is really Brexit biting everyone on the backside.”

The pandemic masked many of the problems created by the Brexit border, Jenkins said. “Easter 2023 was the first hard test of the new regime, and we saw it go horribly wrong in Dover.”

EES and Etias “could be very quick”, he added. “But the first time you do it, it might take a very long time to process. It could be a real bottleneck.”