Meet Your Heroes: The BMW M1 Procar – Speedhunters

Next Chapter >

A Throwback To 2010

If there is one car that’s really struck a chord with me over my years as a Speedhunter, it’s the BMW M1 Procar.

My first sighting of an M1 Procar is a little bit fuzzy in my mind to tell you the truth, but I distinctly remember the first time I ever heard one. It’s not a memory I’ll soon forget.

It was 2010, and I was on my first press trip to the Nürburgring 24 Hour with KW Suspensions. KW had arranged a small group of US auto journalists to attend the race, which I somehow became a part of. I’ve learned that in these instances, it’s better to stay quiet, keep your head down and just hope nobody realises that you probably shouldn’t be there…

It was a typical press trip with tours, presentations, introductions and particularly nice food. While some of the assembled media were happy to absorb as much hospitality as possible, I was itching to get trackside and shoot anything on the Nordschleife. I wasn’t alone. Another photographer who had travelled from California was pretty keen as well. We had only previously spoken before via the Dieselstation forums, but it didn’t take long for Mr. Klingelhoefer and I to hatch a plan.

While we had been allowed some time to shoot trackside on the first couple of corners of the GP circuit, you don’t come to the Nürburgring 24 Hour to shoot within the safety and confines of the GP-Strecke. Especially when you know what awaits you just over the hill.

So, when the very kind KW public relations person was looking the other way (sorry), Sean and I jumped into a media shuttle and basically begged the driver to take us anywhere on the Northern Loop. I don’t think I even had roaming enabled on my phone in 2010, so once we left the paddock, we were essentially MIA. Again, sorry KW.

We lucked it with our driver, who went out of his way and drove us through the camps, along muddy pathways and brought us as close to the track as humanly possible. So much so, that this was the sight right in front of us when we stepped out of the van. What a way to be introduced to the Nordschleife for the first time.

We immediately started walking up the hill from Steilstrecke to the world renowned Caracciola-Karussell. What you might not be aware of is how remote the Karussell is. It’s not really near anything of note.

It was while walking up this hill that I heard an M1 Procar at full noise for the first time. Despite there being a full grid of N24 Classic cars on track, all of which were making their own brilliant noises, there was this distinct sound louder than anything else coming towards us.

In retrospect, and based on how long it took for the car to appear every lap, I reckon we could hear it leaving the village of Adenau on its way to the Karussell.

While not particularly fast when compared to the GT3 cars running in the main N24 race, there was nothing competing that weekend which came close to sound this M1 Procar made. In fact, short of V8-era Formula One cars, I don’t think there have been any cars I have photographed since which match the M1 Procar for its aural qualities. I’ve never heard a video or audio clip that can do them justice.

For the next few years covering the event, I always made a point of ensuring I was trackside for the N24 Classic practice and race sessions to take in whatever Procars might have been competing.

But it’s not just the volume of the cars; it’s the quality of the sound. There’s just something about the distinct tone of this naturally aspirated straight-six screaming to 9,000rpm that I just cannot put into words.

10 Years Later…

It would take quite a few years before I would have the pleasure to see these cars in action when five of them turned up to the 77th Goodwood Members’ Meeting in 2019.

It was at this event where the wheels were finally put in motion to arrange an in-depth shoot of one of the cars pictured above, which happens to live around 30 minutes from where I call home.

Unfortunately, scheduling and Covid put a big delay onto this shoot, but earlier this year it actually happened. I finally got to meet one of my heroes.

Just to break the fourth wall here a little bit, despite how often I have been around this particular car, it’s quite something to be left completely alone with. It’s a special moment which I will forever treasure.

This isn’t just any M1 Procar either, if there can even be such a thing. It belongs to the Martin Birrane Collection at Mondello Park, and is the car which Mr. Birrane won the Group B class in 1982 at the Le Mans 24 Hours alongside Edgar Dören and Jean-Paul Libert. They completed 307 laps and managed to split first and second place in the C2 class in the overall standings, while finishing ahead of numerous C1 category cars.

When Mr. Birrane re-acquired the car some years later, he chose to have it repainted in its original BMW Motorsport colours as opposed to the Le Mans-winning #151 MSW livery.

The origins of the M1 Procar Championship have been well documented. Conceived by Jochen Neerpasch, BMW’s then head of motorsport, and Max Moseley over a few gin and tonics, the one-make championship became a support race on the Saturday afternoon of eight F1 weekends in 1979, pitching the top five F1 qualifiers against some of the biggest names in sports and touring car racing.

It was a simple idea which proved to be enormously successful. I suppose the lure of big prize money didn’t do the championship any harm in attracting names like Lauda, Stuck, Regazzoni, Piquet, Winkelhock, Bürger, Fittipaldi, Mass, Reutemann and many more.

That the top five F1 qualifiers would occupy the first five grid spots with the rest of the M1 Procar grid breathing down their necks from the off only added to the spectacle.

While we know of the legend of the M1 Procar now, and its well deserved icon status, it wasn’t actually meant to be this way. It was originally conceived to compete as Group 5 race car, but a complicated development and production process meant that by the time it was finished, the Group 5 homologation rules had evolved and the M1 was ineligible. So, it went racing in the Procar series as a Group 4 car instead.

Eventually, and perhaps a couple of years too late, several Group 4 cars were converted to Group 5 specification, while Sauber built two of the only ground-up Group 5 M1s, which you can read about in detail on Petrolicious.

They weren’t particularly successful in Group 5, although they did enjoy limited success, which is perhaps why the Group 4 specification Procar is the more renowned of the two.

There are a lot of fascinating things about the M1 and its Procar derivative. There were multiple points during the car’s development where had things gone just a little bit differently, it might never have existed, or could have been a completely different car to the one we have come to know.

As BMW’s first mid-engined car, the aforementioned Jochen Neerpasch commissioned Lamborghini to design and assemble the chassis, which was handled by their own Gianpaolo Dallara. While Dallara created what is widely regarded as a great chassis, Lamborghini’s then financial troubles meant that they wouldn’t be able to produce anywhere near the 400 cars required for homologation, which forced BMW to pull the plug on their involvement.

Instead, the same chassis design was produced by then new Italian company called Marchesi, based not far from Sant’Agata, which evidently consisted of ex-Lamborghini staff who were familiar with the M1 project.

It was Giorgetto Giugiaro, considered by many as one of the greatest car designers of all time, who was responsible for the body work which was bonded to the chassis by his company, Italdesign. By the time the cars eventually arrived back at BMW Motorsport, they still required significant work as the previous stages of manufacturer did not meet BMW’s own strict standards.

Hence the delays, and how we ended up with the Procar. An accidentally brilliant outcome, truth be told.

Despite the car’s complicated history, both the resulting road car and race car were a high point in BMW’s history. Hans-Joachim Stuck recently told Automobilsport that driving the M1 Procar was incredibly easy. “The car wasn’t tricky at all. It was a good handling, very neutrally balanced mid-engine racer with manual transmission, no ABS or anything like it, just the basics. It was a fantastic car to get in and have great fun.”

Coming back to the day of the shoot, I found this a fascinating car to explore and pore over. Even with my limited grasp of race car engineering, it’s pretty easy to look at things and figure out how they work or why they were done a certain way.

With the exceptions of a modern seat, harness and fire suppression system, the car is pretty much as period correct as can be, so you get a proper appreciation for what it would have been like to race one in 1979. There’s so little of anything, anywhere in the car. It’s all so remarkably (and brilliantly) simple. There’s not the abundance and complexity of wiring, control units, sensors, screens and switches as you might find in a contemporary car.

There’s also not as much attention paid to safety either, so there is that to consider.

Behind the gold meshed 16×11-inch front BBS wheels is an ATE brake system with ventilated discs front and rear. The braking system features dual master cylinders with an adjustable brake bias valve.

Underneath the rear, you can see an oil cooler for the differential and 5-speed gearbox. The rear wheels are 16×12.5-inches and Mondello choose to run the car on a semi-slick Avon tyre for all-weather use.

The suspension is double-wishbone, front and rear, with Magnesium uprights, Bilstein coilovers and fully adjustable front and rear anti-roll bars.

As the cars were all as identical as could be, any performance advantages were generally exploited with corner weighting, geometry changes and wing settings.

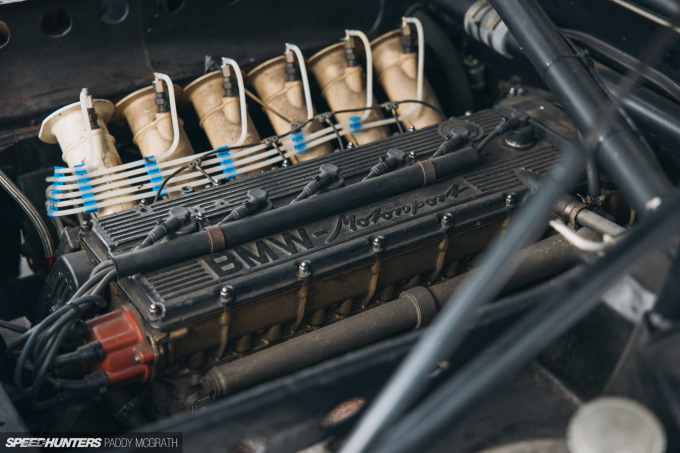

Its party piece, however, is what sits behind the driver. The dry-sumped, 3.5-litre, naturally aspirated inline-six. Or, the M88/1 in BMW parlance.

Although the original plan for the M1 was to receive BMW’s first V10 Formula 1 engine (which ultimately didn’t happen until 2000), they then pivoted to a new inline-six based on the BMW M49 engine from the 3.0 CSi race car. As the M1 was planned to be a road and race car, BMW’s priority was to finish the 400 production cars for homologation first. As the M49 wasn’t suitable for mass production, it had to be adapted with regards to ease of production and emissions standards. A new DOHC cylinder head was the primary change to achieve this.

Paul Rosche, whom had already had success designing BMW’s F2 engines in the 1970s and who would go onto create their turbocharged F1 engines, the E30 BMW M3’s S14 and the McLaren F1 S70 V12, was responsible for the engine. He described the M88/1 (Procar) and M88 (road car) engines as being “close brothers”.

Both were dry-sumped, both featured ITBs and both ran a Kugelfischer mechanical fuel injection setup. The latter of these was a challenge as they wanted to use this fuel injection setup on the race car, so it had to be homologated on the road car, which had strict emissions requirements. They obviously made it work, but not without great difficulty.

The resulting 470hp at 9,000rpm might be some of the most impressive figures ever created, although again, these number weren’t created without issues. One problem they faced as the 1979 season approached was the torsional vibrations caused by the long crankshaft at high revs would force the crank’s vibration damper to come loose. The short-term fix was to double the amount of bolts securing the damper to the crank from six to 12, while long-term a lighter flywheel and other lighter pieces of rotating mass inside the engine solved the issue.

An anecdote I learned while researching this feature was that at the very first Procar race in Zolder, the drivers were instructed not to exceed 9,000rpm. Of course, one driver couldn’t help himself, edged past 9,000 and was immediately overtaken by his own crank damper before retiring from the race. Racecar drivers, eh?

The M1 Procar, and other cars of its ilk, are just so special. They’re from an era which will likely never be repeated; a sweet spot in motorsport and automotive history where things were just the right balance of old and new. That modern cars are so much faster is irrelevant.

This is one of a few cars which I will always be able to appreciate from the outside as just to be in its presence is a gift in and of itself.

While this car is technically a museum piece, it’s wonderful to see and hear it in action so regularly. Just as it should be.

Paddy McGrath

Instagram: pmcgphotos

Twitter: pmcgphotos

[email protected]

The Cutting Room Floor