Mark Twain Was A Travelin’ Man

Mark Twain wrote one of the great, if not greatest, American novels, “Huckleberry Finn,” but in his day, he was better known for the travel books he penned.

His first book “The Innocents Abroad,” published in 1869, tells the story of his journey to Europe and the Holy Land aboard the steamship Quaker City and was the best-selling American book since “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” He became a global celebrity in part because of the tours he went on to lecture about his travel. A new book traces his footsteps around the world.

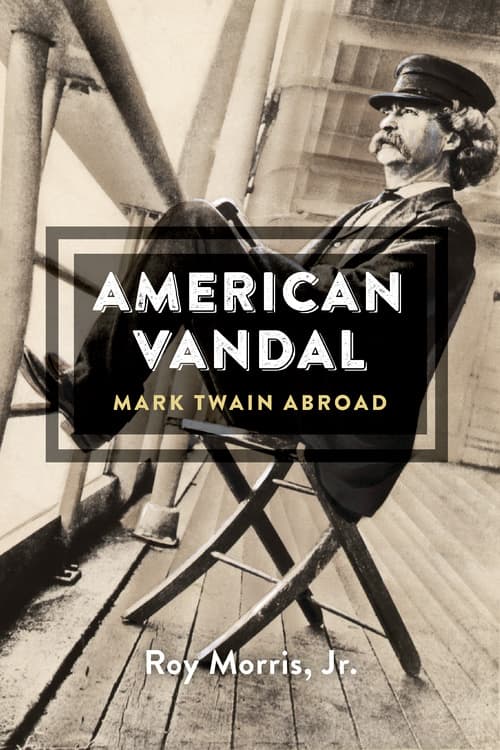

Roy Morris Jr. is the author of “American Vandal: Mark Twain Abroad.”

“There were thousands of travel books printed in the U.S. in the later part of the century,” he told Here & Now’s Jeremy Hobson. “For Twain, [traveling] was actually a way of making money and throughout his career he was more prominently known as a travel writer than a novelist.”

Book Excerpt: ‘American Vandal: Mark Twain Abroad’

By Roy Morris Jr.

INTRODUCTION:

For a man who enjoyed being called—not without reason—the American, Mark Twain spent a surprising amount of time living and traveling abroad. Beginning with his five- month-long visit to Hawaii (not yet a U.S. territory) in 1866, Twain passed the better part of a dozen years outside the boundaries of the continental United States. He made twenty-nine separate transatlantic crossings; circumnavigated the globe via the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans; cruised the Mediterranean, Caribbean, Black, Caspian, and Aegean Seas; crisscrossed India from Bombay to Darjeeling; hiked the Alps and the Tyrolean Black Forest; floated down the Neckar and Rhone Rivers on a raft; and lived and worked for extensive periods of time in London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna, as well as various smaller European cities and resorts. It was all part of his lifelong need to see and experience new things, a need that in itself was deeply and characteristically American. “I am wild with impatience to move—move—Move!” Twain wrote to his mother in 1867. “My mind gives me peace only in excitement and restless moving from place to place. I wish I never had to stop anywhere.” He seldom did.

month-long visit to Hawaii (not yet a U.S. territory) in 1866, Twain passed the better part of a dozen years outside the boundaries of the continental United States. He made twenty-nine separate transatlantic crossings; circumnavigated the globe via the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans; cruised the Mediterranean, Caribbean, Black, Caspian, and Aegean Seas; crisscrossed India from Bombay to Darjeeling; hiked the Alps and the Tyrolean Black Forest; floated down the Neckar and Rhone Rivers on a raft; and lived and worked for extensive periods of time in London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna, as well as various smaller European cities and resorts. It was all part of his lifelong need to see and experience new things, a need that in itself was deeply and characteristically American. “I am wild with impatience to move—move—Move!” Twain wrote to his mother in 1867. “My mind gives me peace only in excitement and restless moving from place to place. I wish I never had to stop anywhere.” He seldom did.

On the fame-making cruise to the Mediterranean and the Holy Land that provided Twain with his first great book-length success, The Innocents Abroad, in 1869, he introduced readers to the American Vandal, a broadly drawn burlesque figure representing the best (and worst) of the national character. The American Vandal, male or female, was a brazen, unapologetic visitor to foreign lands, generally unimpressed with the local ambience—to say nothing of the local inhabitants—but ever ready to appropriate any religious or historical trinket he or she could carry off. Literally nothing was sacred to the Vandal. In an illustration from the book that later was used on the front of its advertising prospectus, Twain cheerfully posed as the Vandal himself, toting a tomahawk, a bow and arrow, and a monogrammed “M.T./U.S.” carpetbag. It was a role he would continue to play, when the mood struck him, for the rest of his life, long after the new had worn off and he had become, as most people do, a sadder and a wiser man.

Twain would write a trio of books about his world travels—The Innocents Abroad, A Tramp Abroad, and Following the Equator—that correspond neatly to the beginning, middle, and end of his writing career. Besides tracking the progress of the author’s personal life, the books reflect the evolving perspectives of American travelers, starting with Twain himself. From the comparatively youthful neophyte in The Innocents Abroad encountering the wonders of Europe and the Holy Land for the first time, Twain grew into the more confident and self-sufficient middle-aged “tramp” who measured a country’s charms chiefly by his reactions to them, and finally into a world-famous international celebrity who dined with the German Kaiser, swapped jokes with the Austrian emperor, traded quips with the king of England, and negotiated with the president of Transvaal for the release of war prisoners.

Like his own country at the turn of the twentieth century, Twain found himself a major player on the world stage. Arthur L. Scott tracks that remarkable evolution: “This raw Westerner was shaped into a New Englander. During the 1880’s he became an ardent nationalist, and finally he grew into a cosmopolite, an internationalist—sage but not serene.”2 Twain’s emergence, personally and artistically, underscored the rise of the American middle class in the latter half of the nineteenth century, a social class whose signature virtues of industry, honesty, and sheer hard work he embodied throughout his life, even after he married into great (if ultimately fleeting) wealth. Unlike the other towering American novelist of the age, Henry James, Twain did not come from the moneyed Eastern elite. He did not grow up in a roomy New York City brownstone, attend Harvard Law School, or spend large stretches of his youth traveling and studying abroad. He did not speak fluent French, revere the English aristocracy, or aspire to a Europeanized existence and sensibility. And again unlike James, who became an English citizen late in life, Twain did not seem embarrassed by his own national identity. He did not desire, as did James, to keep readers guessing whether he was “an American writing about England or an Englishman writing about America.” Everyone knew Mark Twain was an American. Consequently, when Twain first went overseas, he brought America with him, much as James’s title character, the symbolically named Christopher Newman, does in The American: “You are the great Western Barbarian, stepping forth in his innocence and might, gazing a while at this poor corrupt old world and then swooping down on it.” James did not mean it as a compliment.

But if James was a defender of the Old World and its courtly traditional values, Twain was an avatar of the New, training a fresh set of eyes on the glories and ruins of the past. As Shelley Fisher Fishkin has noted, Twain’s travel writings gave other Americans of the time the confidence needed “to stand before the cultural icons of the Old World unembarrassed, unashamed of America’s lack of palaces and shrines, proud of its brash practicality and bold inventiveness, unafraid to reject European models of ‘civilization’ as tainted or corrupt.” Brash, bold, and unafraid himself, Twain encouraged other Americans to follow his example and travel freely, believing that “contact with men of various nations and many creeds teaches him that there are other people in the world beside his own little clique, and other opinions as worthy of attention and respect as his own.” For his part, said Twain, “I am glad the American Vandal goes abroad. It does him good. It makes a better man of him. It rubs out a multitude of his old unworthy biases and prejudices.” So it was for Twain himself.4 Twain was already an experienced traveler long before he first set foot outside the continental United States—indeed, before he was even Mark Twain. Leaving his hometown of Hannibal, Missouri, at the age of seventeen, the youthful Sam Clemens crisscrossed the country for the next six years, working as an itinerant printer in St. Louis, New York, Philadelphia, Keokuk, and Cincinnati before landing his dream job as a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi River, a job that afforded him entry into the exclusive ranks of “the only unfettered and entirely independent human being[s] that lived on the earth.”

He fully intended to remain a riverboat pilot for the rest of his life “and die at the wheel when my mission was ended.”

The advent of the Civil War effectively destroyed those plans and ultimately left Twain stranded back in Hannibal, where he briefly joined a local Confederate militia unit to avoid having to serve as a pilot on Union Army troopships. The few weeks he spent thrashing about the rain-drenched Missouri woods—the sum total of Twain’s military career—were a boyish lark, at least in his later retelling of it. He and the other would-be warriors in the Marion Rangers spent the majority of their time looking for food and shelter, arguing about grand matters of strategy, and dodging imaginary hordes of enemies, including a then little-known Union colonel named Ulysses S. Grant. Finally, “incapacitated by fatigue through persistent retreating,” Twain deserted the Marion Rangers. Like his most famous literary character, he lit out for the territory.

With his brother, Orion, who had just been appointed secretary to the governor of Nevada Territory, Twain embarked on an epic three-week-long stagecoach ride across Nebraska, Colorado, Utah, and the Great American Desert. The brothers arrived in Carson City, Nevada, the territorial capital, in mid-August 1861. The real action was taking place twelve miles to the north, at Virginia City, where the richest silver strike in American history, the fabled Comstock Lode, had been dis- covered two years earlier by a couple of hardscrabble desert rats. In three decades’ time, the lode would yield upwards of four hundred million dollars in gold and silver, and dozens of dirt-poor prospectors would become overnight millionaires. Twain, hoping to join their ranks, spent a few desultory months digging, blasting, picking, and scratching through the stony Nevada soil before discovering his true fortune above ground as a cub reporter on the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. It was there that he adopted his short, punchy nom de plume, taken from his days as a riverboat pilot, and began filling long columns of newsprint with vigorous accounts, sometimes true, of the madcap comings and goings of the various pros- pectors, outlaws, settlers, and loafers in the West’s most rau- cous boomtown.

Eventually Twain abandoned Virginia City for San Francisco, where he pursued his lifelong ambition of becoming a dandy. A few blissful months of “butterfly idleness” ended abruptly when his former partners sold off his nest egg of Nevada mining stock without bothering to tell him about it. Very much against his will, he reentered the workforce as a general assignment reporter for the San Francisco Morning Call, but the newspaper’s eighteen-hour workdays quickly proved to be soul-killing drudgery for someone as professedly lazy as Twain. After four months of enforced servitude, he turned in his resignation. His managing editor was not greatly dismayed.

The unexpected success of his 1865 tall tale “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog,” now better known as “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” gave Twain his first national exposure, and he subsequently spent five months of “luxurious vagrancy” in Hawaii in the spring and summer of 1866, reporting on the islands for his new employer, the Sacramento Union. While in Hawaii he hiked across the floor of an active volcano, surfed the waves off Waikiki Beach, looked into the local leper colony, toured the death site of Captain Cook, climbed mountains, rode horses, smoked cigars, sampled poi, interviewed survivors of a deadly shipwreck, and unsuccessfully courted a bevy of land-rich sugar plantation heiresses. It was a crowded visit.

Upon returning to the States, Twain mounted a well-received lecture tour of California and Nevada, delivering a drolly exaggerated account of his adventures among “Our Fellow Savages in the Sandwich Islands.” The tour added to his growing fame as a writer and humorist, and another newspaper, the San Francisco Alta California, offered him a plum assignment as its roving travel correspondent, “not stinted as to time, place or direction.” The editors sketched out an ambitious itinerary: France, Italy, the Mediterranean, India, China, and Japan. “We feel confident his letters to the Alta will give him a world-wide reputation,” they predicted. They were proved right, if not perhaps in the way they expected. Twain would quickly outgrow the newspaper business.

For the next forty years, alone or with his family, Mark Twain traveled the world as “a self-appointed Ambassador at Large of the U.S. of America,” functioning as both tour guide and tourist. Modern readers are often surprised to learn that the author of perhaps the greatest novel in American literature was much better known in his own time as a travel writer. Certainly it did not surprise Twain, who fell back on his travel writing whenever—and it was often—he found himself financially embarrassed. Wherever he went, he felt at home. “I can stand any society,” he declared. “All that I care to know is that a man is a human being—that is enough for me; he can’t be any worse.”

Whether surfing the waves at Waikiki, trekking the Holy Land in the footsteps of Christ, braving icy ravines in the Swiss Alps, strolling the leafy boulevards of pre–World War I Berlin, riding an elephant through the streets of New Delhi, or clattering by train across the South African veldt, Twain displayed at all times an avid curiosity for his physical surroundings and the baffling, sometimes exasperating people who lived there. He was truly a citizen of the world, and one of the great travelers of the nineteenth—or indeed any—century. “The world is a book and those who do not travel read only a chapter,” said St. Augustine, and Mark Twain in his time read many chapters. He even wrote a few himself.

Excerpted from the book AMERICAN VANDAL by Roy Morris Jr.. Copyright © 2015 by Roy Morris Jr. Reprinted with permission of Belknap Press.

Guest

- Roy Morris Jr., author of “American Vandal: Mark Twain Abroad.” He tweets @roymorrisjr.