Japan in the Olympics, the Olympics in Japan – Association for Asian Studies

Download PDF

The Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics, though still a few years away, has a website providing up-to-date news on every imaginable aspect of the forthcoming event—from the infrastructural changes that Tokyo is currently undergoing to the latest corporate sponsors. The site also outlines the 2020 Games’ “vision,” which includes “passing on legacy for the future.” The organizers state that “the Tokyo 1964 Games completely transformed Japan, enhanced Japanese people’s awareness of the outside world, and helped bring about rapid growth of Japan’s economy. The 2020 Games will enable Japan, now a mature economy, to promote future changes throughout the world and leave a positive legacy for future generations.”1 While this website is, of course, promotional propaganda, it underscores a particular and unusual emphasis that Japan has placed on the Olympics’ potential to evoke positive change in both Japan and the world.

Many readers may know that the 2020 Games will be the fourth Olympic Games to be held in Japan, after the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics, the 1972 Sapporo Winter Olympics, and the 1998 Nagano Winter Olympics. Fewer will realize that Japan has tried to host the Olympic Games on twelve occasions, winning the bid five times if you count the 1940 Games that were canceled due to World War II. This means that Japan has essentially been lobbying, bidding, preparing for, or hosting the Olympic Games almost constantly since the 1930s.2

Because of the Olympics’ global visibility, huge economic impact, and perceived ability to alter a nation’s prestige, the event continues to have great resonance 120 years after it was resurrected as a modern event in Athens. The specific reasons behind Japan’s persistent interest in hosting the event are multifaceted and closely linked to the archipelago’s changing roles in the international and regional geopolitical arenas. In the essay that follows, I trace the history of Japan’s involvement in the Olympic movement and suggest why the nation has devoted such substantial resources toward it for over a century. Regardless of readers’ interest in the sports themselves, it is important to understand both the Olympics’ historical significance and their potential to serve (or not serve) as catalysts for change in the future.

Japan Enters the Olympic Movement

The Meiji Era (1868–1912) slogans “fukoku kyōhei” (“enrich the nation, strengthen the military”), “wakon yōsai” (“Japanese spirit, Western technology”), and “bunmei kaika” (“civilization and enlightenment”) illustrate Japan’s interest in being seen as progressive by the rest of the world—an interest driven largely by a desire to counter Western threats to Japan’s nationhood. Education came to be an important tool of the Meiji government in achieving these nationalistic goals, and this included, for the first time ever, compulsory primary education. The government believed that without a literate and “enlightened” population, Japan would never gain international recognition. As part of the education reform, Western-style physical education was formally required in the elementary curricula for both boys and girls for the first time in 1905.3

One of the key figures in the development of physical education in Japanese schools was Kanō Jigorō. Kanō, a professor and headmaster at the Tokyo University of Education (later the University of Tsukuba), also served in the Ministry of Education. He is perhaps most well-known as the inventor of the sport of jūdō, a form of unarmed combat that combines elements of samurai jūjutsu with techniques meant to bring the traditional martial art into the modern era.4 Indeed, Kanō was very much concerned with modernizing Japan through an emphasis on physical culture, a trend in vogue in Europe at the time. The belief was that physical education strengthened one’s body as well as one’s morals. He felt that the values and lessons learned through modern sports, including not only jūdō, but also swimming, running, tennis, and soccer, could be applied to the daily lives of Japanese citizens.5

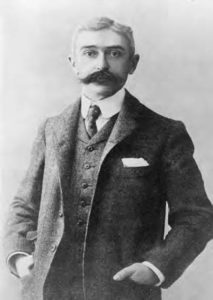

Pierre de Coubertin, the French founder of the modern Olympic movement and President of the International Olympics Committee (IOC) when Kanō was advocating sports for Japan, also believed in athletics for social reform. Since the 1896 revival of the modern games, Coubertin had attempted to recruit nations outside Europe and the United States to participate in the Olympics, but no Asian nation responded. During the run up to the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, Coubertin, in his fight to make the Olympics global, asked the French ambassador in Tokyo to identify a potential Japanese member of the IOC. By the early twentieth century, Kanō Jigorō was well-known in his highly visible role promoting sports for the Ministry of Education. Kanō was also an enthusiastic proponent of internationalizing the previously isolated nation of Japan, having already invited over 7,000 foreign students to study at his university beginning in 1896.6 In 1909, Kanō became the first official Japanese member of the IOC from Japan—and the first Asian to join the organization that was composed of only European and American members. In 1910, the IOC formally invited Japan to take part in the Fifth Olympiad, scheduled to be held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1912.7

Kanō helped select two male athletes to represent Japan at the Stockholm Olympics, a sprinter and a long-distance runner, but had difficulty financing their journey from Japan to Sweden. Few Japanese viewed the Olympics, still a young event, as politically or strategically important enough to warrant Japanese participation. The Ministry of Education did not cooperate with Kanō’s request for funding. Undeterred, Kanō created his own organization, the Dai Nippon Taiiku Kyōkai (Greater Japan Physical Education Association), and named himself President.8 This sports entrepreneur also solicited enough contributions from acquaintances to travel the Trans-Siberian Railway to Stockholm with the two athletes. There, the Japanese athletes quickly learned how outclassed they were in their level of competition.

The sprinter, Mishima Yahiko, finished dead-last in each of his 100-, 200-, and 400-meter races; and his teammate, distance runner Kanaguri Shizō, had an even more embarrassing performance.9 Midway through the marathon, he collapsed, lost consciousness, and was rushed to a local resident’s house for assistance. The Olympic officials listed him as “missing” when he never reported back to them after the race.10 The mediocrity of Japan’s athletes compared to Western counterparts in 1912 was a national wake-up call. Their poor performance set the stage for major structural changes in the world of elite Japanese sports. Before returning to Japan, Kanō visited several European IOC member countries to observe sports and physical education, and to introduce jūdō. In Japan, he subsequently expanded the activities of his Greater Japan Physical Education Association, and actively promoted sports and athleticism as official national concerns. The Ministry of Education established a

nationally standardized system of exercises and sports in 1913, and government subsidies increased exponentially to help promising athletes from elite universities who could be competitive at the international level.11

By the early Taishō Era (1912–1926), Japan had been involved for almost two decades in military campaigns and expansionism, defeating the Qing Dynasty and Russia, and forcefully annexing the Korean peninsula into the Japanese Empire in 1910. A case can be made that by the early twentieth century, Japan’s new focus on creating a stronger Olympic delegation dovetailed with its quest for greater respect in the global order. Japan now possessed a strong military and overseas colonies; greater status in international organizations such as the IOC reinforced the Empire’s new global importance.

Despite the World War I-induced cancellation of the 1916 Olympics, Japanese athletes continued to take part in international sports events such as the Far Eastern Championship Games, where they gained experience and strength through foreign competition. National interest in sports heightened, and as Japan began to win medals and see the Rising Sun flag unfurl at award ceremonies, nationalist sentiments grew stronger. By 1920, when the Olympics resumed in Antwerp, Japan sent a much larger delegation of fifteen men, and the results were much more promising than eight years earlier. Two tennis players brought home Japan’s first Olympic medals.12

Japan began to define itself in international sports as a competitive opponent. The Meiji Shrine Games were inaugurated in 1920 as a competitive domestic championship event and also featured women’s sports divisions. By 1928, over 200 female athletes were competing in track and field, gymnastics, archery, equestrian events, rowing, swimming, tennis, table tennis, basketball, field hockey, and volleyball.13 Later that same year, a phenomenal female track star named Hitomi Kinue brought home a silver medal from the 800-meter race at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics in the first year that women’s track and field events were introduced.14 The level of performance among Japan’s elite athletes, based on the number of Olympic events in which they took part and by the number of medals they won, was on the rise.

The 1940 “Phantom” Tokyo Olympics

As fervent nationalism fed into a desire to perform better, and as performing better fed into the fervent nationalism of the early 1930s, the Olympic Games took on a greater significance in the public imagination. In order to position itself on more equal footing with powerful European nations such as France, England, and Germany, Japan set its sights on hosting the Olympics. The year 1940 coincided with a huge commemoration, the alleged 2,600th anniversary of the founding of Japan, according to the eighth-century chronicle Nihon Shoki. In 1936, shortly before the Berlin Olympics, the IOC announced that Tokyo had won the bid to host the 1940 Games. Japanese fans eagerly followed the Berlin Olympics, where the Japanese delegation did very respectably, capturing six gold and a total of eighteen medals. The recent invention of live radio broadcasting enabled fans back in Japan to cheer for their national champions in real time, adding to the nationalist excitement.15

In stark contrast to the glory and pride on display at the 1936 Olympics, in the late 1930s, Japanese military and political leaders were marching the nation into one of the darkest periods of modern Japanese history. Japanese aggression and Imperial control were spreading throughout Asia. In 1937, the year after the Berlin Olympics, Japanese forces killed hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians in the infamous Nanjing Massacre. Japanese aggression would likely have led to some nations boycotting the Tokyo Olympics. However, it was the cost of pursuing the full-scale “holy war” with China that led the Japanese in 1938 to forfeit hosting the 1940 Games.16

During World War II, physical education in Japanese schools became militarized, and by 1943, the government had banned most recreational sports and instead promoted martial arts.17 After surrendering to the Allied Powers in 1945, despite the immense work needed to restore the sports infrastructure, restoring recreational sports became a national priority. During the Allied Occupation (1945–1952), General Douglas MacArthur encouraged Japanese citizens to participate in baseball and other modern sports tournaments. Just three weeks after the instrument of surrender was signed by Japan, Tokyo University students held their first postwar rugby tournament, and national leagues in baseball and basketball were resurrected the same year.18 Just one month after the Allied Occupation ended in April 1952, Tokyo Governor Yasui Seiichirō proposed that Japan again bid to host the Olympics. Yasui argued that Japan’s hosting of the Olympic Games would allow “the true Japan, now restored to peace, to return to the international stage and have the real Japanese, who sincerely aspire to world peace, be recognized by the people of the world.”19 Tokyo’s 1960 Olympic bid was lost to Rome (another WWII Axis power looking to reinvent itself on the global stage), but they tried again in the next bidding cycle; and in 1959, the IOC announced that Tokyo would host the 1964 Summer Olympics.

The Transformative 1964 Tokyo Olympics

While there are parallels between Tokyo’s Olympic bids for the 1940 and 1964 Games in that both times the nation hoped to use the event as an opportunity to highlight their equality with advanced Western nations, other objectives underlying the two bids were quite different. In the 1930s, Japan used the Olympics to emphasize that it was more advanced than the rest of Asia and should therefore expand its sphere of influence. The government hoped the 1964 Tokyo Olympics would assure the world that Japan had reemerged as a peaceful and economically successful country, and show

Japanese citizens that Japan’s national “spirit” remained strong and intact in spite of the devastation and loss incurred during the War.20

The hosting of the Tokyo Olympics was an opportunity for Japanese leaders to cautiously rebuild a sense of nationalism after the traumatic excesses of WWII. Some of the most controversial symbols of Japanese nationhood—the Emperor, the Rising Sun flag, and the national anthem— reemerged as peaceful symbols of the nation. One of the most poignant symbolic moments of the 1964 Opening Ceremonies was when Sakai Yoshinori, also known as “Atom Boy,” lit the Olympic flame in the National Stadium. Sakai had been born in Miyoshi, Hiroshima Prefecture, on August 6, 1945, the day Hiroshima was leveled by an atomic bomb. In 1964, as a first-year student and aspiring sprinter at Waseda University, he was chosen as the final torchbearer to symbolize Japan’s postwar reconstruction and peace.21

The 1964 Olympics is frequently referenced in narratives about how quickly and successfully Japan “rose like a phoenix from the ashes” after the war. The bullet train opened just in time for the Opening Ceremonies, and TV sets across the country and throughout the world were tuned in to the seamless, technologically advanced event in which Japan won twenty-nine medals—more than half of which were gold. Kanō’s sport of judō was included in the Olympics for the first time. Washington Heights, which had been the gated base that housed members of the Allied Occupation from 1945 to 1952, was converted into the Olympic Athletes’ Village, a symbolic transfer of space in the center of Tokyo.22 After the Olympics, the space was converted into a large, beautiful park.

The 1964 Games took place at such a pivotal moment in Japanese history and seemed to pave the road for many years of rapid development and successful global reintegration. Perhaps as a result, the Olympics today have a special place in the Japanese public imagination. This is particularly true among many now-aging baby boomers, including some powerful politicians, who were high school or university students in 1964. These political leaders’ views and priorities regarding the Olympics do not necessarily align with those of the Japanese public today.

Japan’s Olympic Future: The 2020 Olympic Games

When it was announced in 2013 that Tokyo would once again host the Olympic Games in 2020, these boomer politicians, including Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, expressed excitement and hope that the

event might be a catalyst for positive change in twenty-first-century Japan. In his address to the IOC at their 125th session in Buenos Aires, where Tokyo was later announced as the winner of the 2020 bid, Abe stated, “When I close my eyes, vivid scenes from the Opening Ceremony in Tokyo in 1964 come back to me . . . We in Japan learned that sports connect the world. And sports give an equal chance to everyone. The Olympic spirit also taught us that legacy is not just about buildings, not even about national projects. It is about global vision and investment in people.”23 However, Abe’s enthusiasm seems conspicuously unmatched by much of the Japanese public as plans are set in motion for the 2020 Games. Instead, the decision for Japan to host the Games has received intense criticism in the media, and the initial planning stages have been marked by controversy and missteps.

As Japan’s economy has been in a period of stagnation for over two decades, the amount of money (including taxes) that will go toward this event has become a central issue of concern among Japanese citizens. The stadium built for the 1964 Olympics, with a seating capacity of over 54,000 and in use until 2014, was recently demolished in order to be replaced by a huge 80,000-capacity stadium in central Tokyo. Protesters and prominent environmentalists and architects spoke out against the new stadium, which was designed by British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid and carried a staggering price tag of over 250 billion yen (or US $2.2 billion making it the most expensive stadium ever built).24 Polls in major newspapers indicated the public was uneasy about the project moving forward without any consultation with Tokyo residents, who will most probably be footing the bill for generations to come.25

Following the steady criticism of the stadium project, Abe made a sudden announcement that the entire plan for the new stadium was to be scrapped in July 2015. A few weeks later, event organizers also withdrew the Tokyo 2020 logo that had been selected amidst plagiarism accusations. This led to an ongoing stream of commentary in the media that the 2020 Olympics had inept leadership and were misguided in many regards. The February 2016 edition of the popular scholarly journal Sekai declared on its cover, “Rinen naki tokyo orinpikku” (“The Tokyo Olympics with No Concept”). The volume contains articles in which academics, essayists, and journalists systematically critique and tear apart the troubled rollout of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

The forthcoming Tokyo Olympics, of course, are not alone in stirring up controversy among the public—such megaevents always have a sizable group of detractors who oppose using taxpayer money to fund spectacles that benefit few and burden many. Recent Olympics have shown that citizens from Athens to Rio de Janeiro are reacting to the Olympics as more wasteful and excessive vanity projects rather than important opportunities to showcase national prestige. That said, the current debates surrounding the 2020 Tokyo Games may indeed be highlighting different avenues for change to be effected in Japan. Although a stereotypical image of Japan as a place where change is imposed from above still persists, the current protests and problems with the 2020 Olympic plan rollouts are indicative of a different kind of change taking place. It is too early to determine whether actual change might take place from below, but it is clear that, regarding the Olympics, the top-down model, highlighted by a lack of transparency and little public input, is under serious scrutiny in Japan today.

Japan’s citizens and politicians are well-aware of the precarious place that the nation currently stands within the global economy. While economists will attempt to quantify and perhaps justify the hosting of the Olympics by pointing out the economic benefits that the event will bring (a highly questionable proposition, given the massive infrastructural and public works projects that go hand in hand with these events), the social and political implications of the event will be much harder to prove. Perhaps it is precisely these intangible benefits that are difficult to measure, such as a possible improved national image that could boost tourism and investment or the reemergence of Japan into the global public consciousness, that will indeed prove to be the catalyst about which Japanese bureaucrats dream. As the 2020 Olympics approach, I hope that readers will follow the news with a clearer sense of the historical significance of the Olympics for the Japanese nation, and of how both Japan and the Olympic Games might change in intended or unintended ways.

Text Box on Yūki Kawauchi:

The Citizen Runner Many runners in Japan, including the nation’s current most famous runner, are not Olympians, but in Yūki Kawauchi’s case, amateurs. Government employee during the week, star marathon runner on weekends, Kawauchi has become Japan’s most famous nonprofessional athlete. Known in Japan as “The Citizen Runner,” Kawauchi has been training since age seven, when his mother put him through grueling sessions where he would have to beat his best time every day or run extra laps. Some days ended with an ice cream or burger for a reward and others ended with him jogging home alone for two miles. He has become a hero with Japanese citizens because of his everyman appeal and defiance of the status quo in Japanese athletics. He doesn’t take corporate endorsements and pays all his race-related expenses out of pocket, once paying about US $9,000 (about three months’ salary) to buy a last-minute ticket to a race in Egypt.

Kawauchi was never a standout in high school, largely due to injuries sustained by his poor form, and no university track coach recruited him. He attended Gakushuin University, a school known more for academics than athletics, and joined the track team. After his college coach changed Kawauchi’s running habits, his performance drastically improved. Ekidens are long-distance relay races that are wildly popular in Japan. In 2006, Kawauchi qualified for the most famous ekiden, Hakone, a two-day-long university men’s relay of ten roughly thirteen-mile legs that cover a distance from downtown Tokyo to the town of Hakone and then back that is watched by millions of Japanese. Kawauchi finished third in his leg—a feat still famous today. At the beginning of the 2014 Hakone Eikiden, Japanese students handed out a newspaper with his tortured running face on the cover and the headline “The Legend of Passion.”

Kawauchi ran his first marathon, the Beppu-Oita Mainichi Marathon, in 2009 with a time of two hours, nineteen minutes, and twenty-six seconds. He ran the Tokyo International Marathon the next month with a time of 2:18:18 and finished nineteenth. Despite not running for a corporate team (Japanese corporations pay runners to participate in professional ekiden teams rather than in individual marathons), Kawauchi would continue to train rigorously around his forty-hour-a-week job for the Saitama Prefectural government using weekends and most of his twenty-five days off to travel and participate in races. In the 2011 Tokyo Marathon, he finished third overall and first among Japanese with a time of 2:08:37. In his next fifty-one marathons, he won twenty-three and finished in the top three in thirty-one.

NOTES

1. Translation taken from the abbreviated English version of the 2020 Olympics’ home page at http://tinyurl.com/z4qmzl6. 2. Japan’s Olympic bidding history is as follows: Summer Games: Tokyo 1940 (awarded/ canceled), Tokyo 1960 (failed), Tokyo 1964 (awarded), Nagoya 1988 (failed), Osaka 2008 (failed), Tokyo 2016 (failed), Tokyo 2020 (awarded); Winter Games: Sapporo 1940 (awarded/canceled), Sapporo 1968 (failed), Sapporo 1972 (awarded), Sapporo 1984 (failed), Nagano 1998 (awarded).

3. Allen Guttmann and Lee Thompson, Japanese Sports: A History (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001), 115–116. 4. Ibid., 100–104. 5. Hisashi Sanada, “The Olympic Movement and Kanō Jigorō,” Japanese Olympic Committee, accessed July 11, 2016, http://tinyurl.com/h2yacqf. 6. Ibid. 7. Guttmann and Thompson, 117. 8. Sandra Collins, “Introduction: 1940 Tokyo and Asian Olympics in the Olympic Movement,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 24, no. 8 (2007): 963. 9. The poor performance by these athletes at the 1912 Olympics belies the high level of competition that was emerging domestically in Japan at this time. Thomas R. H. Havens’s Marathon Japan: Distance Racing and Civic Culture (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2015) offers a detailed overview of Japan’s thriving running culture in the 1910s–1930s in chapter 2 (“Racing to Catch Up”).

10. The story has a heartwarming ending. In 1967, when Kanaguri was seventy-five years old, he received an invitation from the Swedish National Olympic Committee to return to Stockholm to take part in the fifty-fifth anniversary celebrations of the 1912 Olympics. There, he was asked to “finish” the race from the point at which he had passed out, and he happily did. His time was read out as “54 years, 8 months, 6 days, 5 hours, 32 minutes and 20.3 seconds.” See Edan Corkill, “Better Late Than Never for Japan’s First, ‘Slowest’ Olympian,” Japan Times, last modified July 15, 2012, http://tinyurl.com/zadtnca.

11. Sanada, 1.

12. Guttmann and Thompson, 119.

13. Ibid., 120–121.

14. Hitomi’s outstanding performance at both the Olympics and at other national and international events had a profound impact on women’s involvement in competitive sports in Japan in the early twentieth century. For a detailed discussion, see chapter 4 of Robin Kietlinski, Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo (London: Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2011).

15. Kazuo Hashimoto, Nihon supōtsu hōsō shi [The History of Japanese Sports Broadcasting] (Tokyo: Taishūkan Shoten, 1992), 17.

16. For a detailed treatment on how the decision to forfeit was reached, see Sandra Collins, The 1940 Tokyo Games: The Missing Olympics: Japan, the Asian Olympics, and the Olympic Movement (New York: Routledge, 2007).

17. Guttmann and Thompson, 159.

18. Ibid., 163.

19. Collins, 181.

20. Ibid., 182.

21. Christian Tagsold, “The 1964 Tokyo Olympics as Political Games,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 7, issue 23, no. 3 (2009).

22. After the Olympics, all but one of these housing units was torn down and the space was converted into Yoyogi Park. See Masahiro Takeuchi, Chizu de yomitoku tōkyō gorin [Analyzing the Tokyo Olympiad through Maps] (Tokyo: Besuto shinsho, 2014), 105–107.

23. For the entire text of this speech, which Abe delivered to the IOC in English, see “Presentation by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the 125th Session of the International Olympic Committee (IOC)” at the Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet’s website at http://tinyurl.com/h7h5mrk.

24. An organization of concerned citizens called The Custodians of the National Stadium Tokyo maintains an excellent website that details the many controversies surrounding the National Stadium project (in Japanese): http://2020-tokyo.sakura.ne.jp/

25. For example, a July 2014 telephone poll of 1,000 adults between the ages of twenty and sixty conducted by the Nihon Keizai Shimbun (Nikkei) noted that 85 percent of those polled believed that the Tokyo Olympic facilities should be reconsidered. Concern over the cost of new construction was cited as the No. 1 reason people felt the plans should be rethought. See「東京五輪の施設計画「見直し賛成」85 % (“85% Favor Revision of Tokyo Olympics Plans”) Nikkei Shimbun, July 21, 2014. Translation by the author.

ROBIN KIETLINSKI is Associate Professor of History at LaGuardia Community College of the City University of New York. Her research focuses on the intersections of sports and society in modern Japan. Her book, Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo (Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2011), explores the history of Japanese sportswomen, including their participation in the Olympic Games beginning in 1928. At LaGuardia, Kietlinski teaches courses in global history, East Asian civilizations, and Japanese history.

ROBIN KIETLINSKI is Associate Professor of History at LaGuardia Community College of the City University of New York. Her research focuses on the intersections of sports and society in modern Japan. Her book, Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo (Bloomsbury Academic Press, 2011), explores the history of Japanese sportswomen, including their participation in the Olympic Games beginning in 1928. At LaGuardia, Kietlinski teaches courses in global history, East Asian civilizations, and Japanese history.