Deep in debt: Eight artists American Apparel ads owe their aesthetic to | CBC Arts

It’s an American Apparel scandal that, for once, has nothing to do with allegations of workplace misconduct or pants-optional advertising. The Los Angeles by way of Montreal clothing company filed for bankruptcy this week. Despite facing more than $300-million in debt, American Apparel says it’s still business as usual for much of their operations. Stores will remain open and they’ll keep cranking out Made-in-the-U.S.A. crop tops, tube socks and leggings for the foreseeable future. Still, the news rings as the end of an era, one marked by an advertising aesthetic known for a different sort of bankruptcy.

You know the look, especially from their banned-in-the-U.K. fashion campaigns: on-camera flash; high saturation; painfully-young-looking “amateur” models. Amy Schumer best described the ad’s subjects in one of her stand-up routines: “I like that every shot of them, it looks like a shot of the last time they were ever seen. It looks like they are waiting for Liam Neeson in the bottom of a closet. It’s like hostage lighting.”

Those hostage lights? They were killed earlier this year when the company announced they’d be ditching “the nudity and blatant sexual innuendo” in their ads after dedicating years to perfecting the art of the sleaze. It’s an art they share with a variety of sources, some more NSFW than others, and CBC Arts is testing the limits of your workplace firewall to list a few. These are a few artists who may or may not have influenced the look, the feel — or the no-no feeling — of American Apparel’s most infamous ads. Some work in advertising, including campaigns for AA itself. But they didn’t start doing what they do to sell you socks and panties.

Nội Dung Chính

Juergen Teller

Sex and “hostage lighting” sells, and American Apparel isn’t the only company that knows it. Just look to campaigns for Marc Jacobs or Celine or Vivienne Westwood — all of which were shot by fine-art photographer Juergen Teller to more cheeky than creepy effect.

(Marc Jacobs)

(Marc Jacobs)

Terry Richardson

White wall, head-on view, blinding flash: that’s Richardson’s go-to set-up, a candid aesthetic that’s totally, and repeatedly, constructed for everything from magazine covers to, well, American Apparel ads. It’s a signature look as infamous as the fashion photographer himself. Richardson has been a continuous presence in mainstream fashion and pop (see Miley Cyrus’ “Wrecking Ball” video, or Beyonce’s “XO”). He has also been accused of sexual assault and harassment by numerous models, though none of the allegations have been proven in court. Other people associated with American Apparel have faced allegations of impropriety. Dov Charney, the AA founder, was ousted by the board after it conducted an investigation into alleged misconduct, including sexual harassment and misuse of company funds. Similarly, none of the allegations against him have been proven in court, and Charney is suing the company for defamation.

(Vogue Hommes Japan)

(Vogue Hommes Japan)

Larry Clark

It “watches like a 90-minute American Apparel advert.” That’s how The Guardian described the experience of re-screening Larry Clark’s Kids earlier this year, on the occasion of its 20th anniversary. But even the director’s earliest photo-documentary projects — Tulsa (1971) for example, and Teenage Lust (1983) — evoke that same unsettling, ultra-real teenage underworld. Clark once described the former collection as “a record of his secret teenage life,” black-and-white photos of his childhood friends shooting drugs and guns in Tulsa, playing at being rebels in the suburbs, while creating honest images so shocking Clark reportedly wanted to burn the negatives when he first saw them developed.

A scene from Larry Clark’s Kids (1995). (Handout)

A scene from Larry Clark’s Kids (1995). (Handout)

Ryan McGinley

Like Larry Clark’s Tulsa, Ryan McGinley’s The Kids Are Alright (1999) is a photo diary of youth in revolt. It’s all sex, drugs and skinny dipping — a collection of lo-fi photographs, featuring the artist’s pals at the time. By 2003, McGinley was the youngest artist to ever mount a solo show at New York’s Whitney Museum, and he’s described early works like The Kids are Alright as “evidence of fun.” Indeed, there’s something innocent and joyful, rather than disturbing, about the subjects — making the series seem like a taste-making scrapbook of a debauched moment in time.

The Kids Are Alright, 1999. (Ryan McGinley)

The Kids Are Alright, 1999. (Ryan McGinley)

Balthus

Maybe AA saw a kindred spirit in the mid-20th century Polish-French artist, because in late 2013 graphic designer Linda Eckstein blogged about a curious matchy-matchiness at work in AA’s print campaigns and Balthus’ sexually charged paintings. Both feature eroticized subjects, sure, but the really striking similarity is the composition. Yeah, nobody would ever lounge around the house like that. Unless you’re an American Apparel model maybe.

(Allmyeyes.blogspot.com)

(Allmyeyes.blogspot.com)

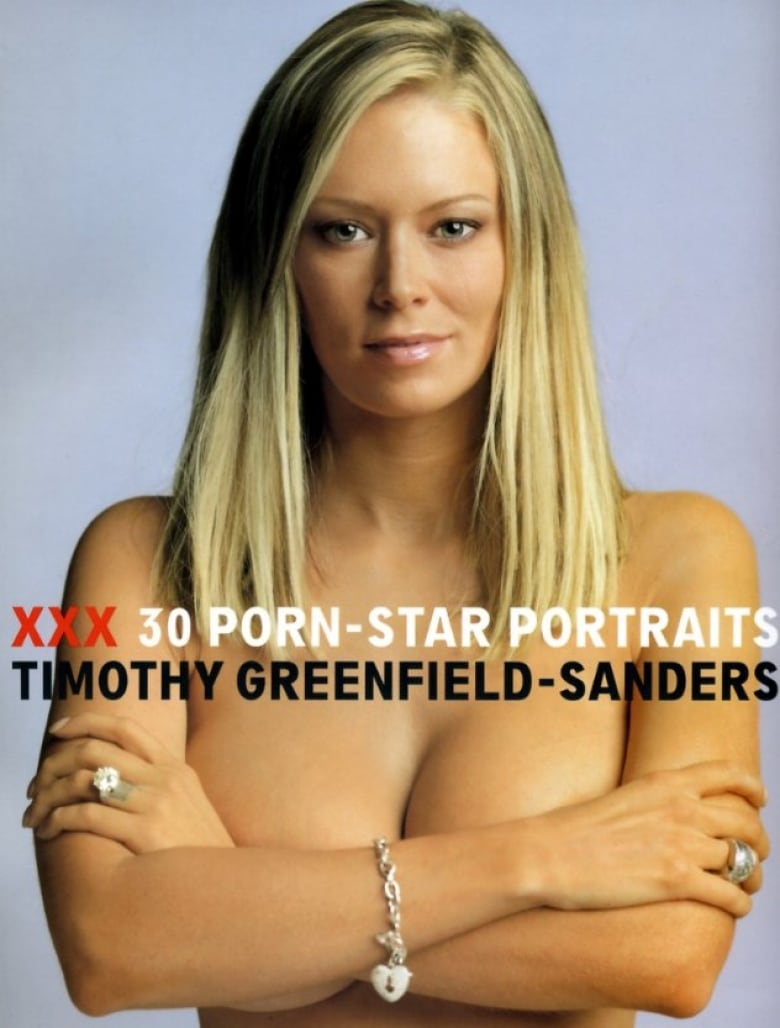

Timothy Greenfield Sanders

He’s photographed presidents and entertainment legends, and his 2004 photo book XXX was a collection of porn-star portraits — both clothed and nude — mixed with essays by the likes of Lou Reed, Salman Rushdie and John Waters. The idea behind the project was to discuss the “pornification of the culture at large.” And by 2008, AA’s own contribution to that trend involved a print campaign where they, too, recruited porn stars to go mainstream, posing for a series of ads.

(Handout)

(Handout)

Yasumasa Yonehara

Lo-fi erotica, shot on instant film. That’s the world of Japanese photographer Yasumasa Yonehara, known for photo books including Tokyo Amour and Sneaker Lover, a 2008 project for clothing company KIKS TYO. It’s also the world of American Apparel advertising — and according to Yonehara, that’s just ’cause the company ripped him off. In a 2009 interview with MEKAS, the artist was forthright with his accusations, alleging American Apparel “started to make stuff exactly like my photos, down to the composition and colours.” He continued: “There is something kind of painful about it. Dov [Charney, former CEO of American Apparel] very skillfully took my methodology and made it work within a commercial context.”

(Handout)

(Handout)

That pile of old Penthouse magazines you found in your uncle’s basement.

Well, obviously.