American psycho Rolex

EDITOR’S PICK: Why Rolex’s problem with American Psycho goes deeper than a chainsaw-wielding maniac

Time+Tide

EDITOR’S NOTE: This week, in a video posted online, Patrick Schwarzenegger reads aloud the famous opening monologue from the film, American Psycho: “My name is Patrick Bateman. I’m 27 years old. I believe in taking care of myself, and a balanced diet, and a rigorous exercise routine… There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman. Some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me.”

The video was released to publicise a photoshoot, appearing in the September issue of Vanity Fair, that celebrated the most memorable characters of turn-of-the-century cinema. But it’s yet another example of how American Psycho still percolates through the public consciousness. So we thought we’d take another look at Luke’s examination of why Bateman’s Rolex Datejust 16013 continues to cast a large and slightly problematic shadow.

Patrick Bateman is an unlikely pop cultural icon. Yet that’s exactly what the anti-hero of American Psycho has become. Almost 30 years since Bret Easton Ellis’ book was published, and 20 since the movie’s release, Bateman’s Armani-clad mass murderer continues to resonate in the contemporary psyche.

Type his name into Google and you’ll find a cosmetic brand named after him (Bateman Skincare), a LinkedIn post offering “American Psycho’s Top 10 Personal Branding Tips” and various first-person articles of the “I Followed Patrick Bateman’s Psychotic Skincare Routine For a Week” variety. Fascination with the film, in particular, has reached seriously nerdy levels. (FYI the “whoosh” sounds made when the characters brandish their business cards in the famous scene was made by slowing down the sound of a sword being drawn from its sheath.)

Anyone who’s read the book — still banned in the Australian state of Queensland — may find this fan-boy veneration slightly awkward. The film presented a sanitised version of Bateman as a fairly standard chainsaw-wielding maniac. But the book is essentially torture porn in designer threads.

Unfolding with a stylised tone of glazed indifference, the novel reveals Bateman as a serial killer, necrophile and cannibal who occasionally snacks on his victims’ rotting entrails. Soundtracked by Huey Lewis and the News, the depravity of Bateman’s murder spree is truly horrific. He kills a five-year-old child at the penguin habitat in Central Park Zoo and does something too despicable to mention to a prostitute using a starving rat. In short, this is one seriously evil dude.

How then did Bateman come to be regarded today with something close to indulgent affection?

It helps, of course, that most people’s familiarity with the character is restricted to the film, a jet-black comedy that satirised the terminal shallowness of 1980s New York. But the true reason that Bateman has become such a cultural reference point is that he became the first poster-boy for a particular form of male narcissism.

“Is There A Bit Of Patrick Bateman In All Of Us?” asked Mr Porter in an article to tie-in with American Psycho: The Muscial. They weren’t referring to his homicidal tendencies either. When the book was released in 1991, Bateman’s Wall St banker was one of the first male faces of image-conscious preening that has since gone mainstream. Bateman works out ferociously (1000 daily crunches) and religiously follows a nine-step skincare regimen. While his self-care rituals were hyperbolically extreme, what they showed back then was a rare example of a man willing to take serious care of his appearance. As anyone who’s flicked through GQ or Men’s Health will know, today it’s not only acceptable for a guy to look after himself, to a certain degree it’s expected.

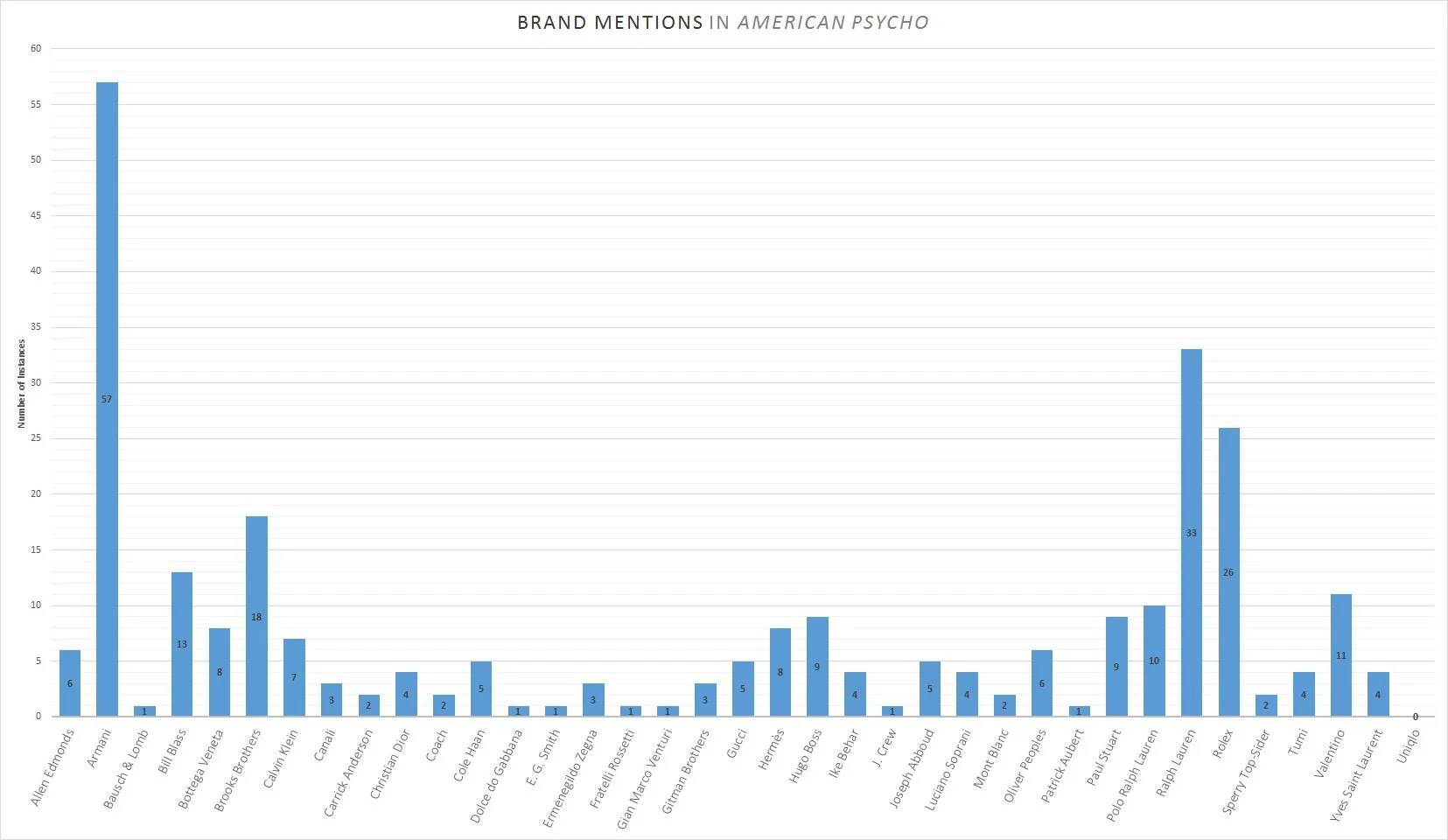

The most visible manifestation of all this is Bateman’s pathological obsession with designer labels. More than 36 clothes brands are name-dropped throughout the book – Armani alone is mentioned 57 times. The constant listing of clothing worn by each and every character is used to demonstrate the rabid materialism of a culture in which value is dependent on superficial appearance. American Psycho is a cold-eyed treatise on commodity fetishism. Which brings us nicely along to Bateman’s watch.

Of course, it had to be Rolex, a brand mentioned 26 times in the book, the third most frequently mentioned brand after Armani and Ralph Lauren respectively. More specifically, it’s a Rolex Datejust 16013, a masterful choice for the pinstriped wrist of a 1980s banker.

Two-tone watches have undergone a form of rehabilitation of late. Softened by nostalgia, their inherent flashiness has moved into the playfully ironic realm of retro cool. But make no mistake: they couldn’t be any more ’80s if they were wearing a Walkman and Reebok Pumps.

Within the Datejust’s look-at-me colour scheme, the gold fluted bezel encircles a gorgeous tapestry dial that adds real depth and shimmer. The jubilee bracelet is also on-point for Bateman, offering a dressier feel than the standard Oyster — a salient detail of one-upmanship that he would inevitably relish.

Famously, however, Rolex were not happy about this product placement. Using the sort of influence that only one of the world’s most powerful brands can muster, they contrived to get the brand’s name omitted from the film. The book offers a scene in which Bateman is cavorting with two prostitutes in which he utters the line, “Don’t touch the Rolex.” In the film, the line had to be changed to: “Don’t touch the watch.”

The received wisdom is that Rolex didn’t want to be associated with a monstrous sociopath. But even if it wasn’t for his penchant for dissecting women, Bateman would still be a bad look for the brand. Take away his gruesome acts of violence and the man is still a phenomenal jerk.

Bateman is so mind-bogglingly shallow that you wonder if he even casts a shadow. He is infatuated with materialistic trophies for their ability to be weaponised in his endless battles of social one-upmanship. This is a serious matter for Bateman. As he mentions with horror in the film’s voiceover, “There is a moment of sheer panic when I realise that Paul’s apartment overlooks the park and is obviously more expensive than mine.”

Given this fixation, there’s no surprise at his choice of watch brand. Because if you select a timepiece based purely on its strength as a social-signifier then you’ll always go for a Rolex. Yes, some brands may also boast equally storied histories. A few even produce watches of similar quality. But if you just want your watch to broadcast the size of your wallet to the widest possible audience, Rolex is the status symbol par excellence.

Horologically, of course, Rolex stands for much, much more than this. They have an extraordinary track record for technical innovation, a truly illustrious heritage and their watches are famously dependable. No one can deny that Rolex make very, very fine watches. Yet people like Bateman opt for the brand not because of the ingenuity of their Parachrom balance springs but for what it stands for. A gold Rolex makes a very clear and obvious point. You don’t need to know your bezels from your Basels to appreciate it’s an unmistakeable emblem of money and power.

That’s why, in the movies particularly, Rolex watches are often used as shorthand for demented capitalism. Think of Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross, the aggressive baller from head office who scathingly berates a room full of salesmen with the line: “You see this watch? That watch cost more than your car.” The watch in question is, of course, a Rolex. Flaunting a Patek or Breguet just wouldn’t have the same effect.

None of this is Rolex’s fault. Many brands fall foul of negative associations – one thinks of how Burberry’s check-pattern caps became embraced as the British football hooligan’s headgear of choice in the 1990s. Indeed, the fact that a gold Rolex is a marker for conspicuous consumption is probably more of a brand strength than a weakness. The overt nature of the statement might not be to everyone’s taste. But it shows how the brand has become inextricably linked with modern notions of success.

The problem with Patrick Bateman’s Datejust was not that it was ever going to make Rolex the serial killer’s watch of choice. The real issue was that his noisy patronage of the brand positioned Rolex as the logical choice for the ultra mercenary and materialistic. That perhaps is the unavoidable price of Rolex’s phenomenal success, but as the old saying goes: heavy is the head that wears the crown.