American Apparel: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an All-American Business – The Fashion Law

American Apparel was not necessarily destined for greatness when its founder – then just a college student named Dov Charney – had a business idea: he would sell t-shirts. Yet, within the past ten years, American Apparel has been in the news consistently for a variety of reasons. There were the scandalous advertising campaigns, for which the brand has become known; there was the news of its early financial success; and its staunch dedication to manufacturing in downtown Los Angeles; among other things.

For much of the brand’s life, its racy ad campaigns received the vast majority of press coverage – at least until recently, but arguably even more noteworthy is the rise and subsequent fall of this affordable fashion empire, complete with the ouster of its founder and chief executive officer Dov Charney, a handful of ugly sexual harassment lawsuits, two Chapter 11 bankruptcy filings, and its subsequent delisting from the New York Stock Exchange.

The question is: How did a company that less than ten years ago was deemed one of the fastest growing companies in the United States, boasting a rate of growth of 440% over a three-year period at one point and annual revenues that topped $211 million, get to this point?

Nội Dung Chính

The Making of an All-American Brand

To determine how a company with so much promise could come crashing down so very publicly and disastrously, we have to start at the beginning, in 1989, when Charney got his start selling t-shirts out of his dorm room at Tufts University near Boston, only to ultimately drop out before graduation to pursue the endeavor full time. After settling in Los Angeles in 1997, Charney began to make waves, challenging the labor standards of the local garment industry by paying higher wages (two times higher than the standard wage at times) and providing benefits for his laborers, all while touting his company’s mission of removing the widespread norm of exploitation from the garment manufacturing process.

As of the start of the millennium, American Apparel was operating primarily as a wholesale business, selling ethically-manufactured blank t-shirts, and “related garments, such as panties” as it noted in an early marketing flyer, which included photos of scantily clad girls and Mr. Charney, himself. The ethos of quality (both in terms of the garments and the experience of its factory employees) and overt sexuality run to the core of company, dating back to its earliest days.

The budding company opened its first store in 2003, expanding to 143 stores in 11 countries by 2007, with garments and accessories for men, women and children lining its shelves. The American Apparel name would become synonymous with unbranded and moderately priced t-shirts, sweatshirts, jeans, and undergarments. It would become known for others things, too, as illustrated in a 2004 feature in Jane magazine, entitled, “Meet Your New Boss,” which detailed the brand’s real estate expansion plans, its choice of models, and Charney’s pattern of lusting after his young employees.

As of the time of publication, around the same time that Charney was named an Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the Year, he had been in serious relationships with three of his underlings. The most talked-about aspect of that Jane magazine article, however, was the part where writer Claudine Ko noted that Charney openly masturbated in front of her during their interview. The incident was, somehow, largely pushed under the rug.

In an attempt to find the “necessary financial foundation to give us the opportunity to realize our bigger dreams,” Charney announced in December 2006 that Endeavour Acquisition Corporation, a publicly traded investment company (that praises Charney as a revolutionary businessman) had bought American Apparel. Still a “relatively new company in the U.S. clothing business,” as MarketWatch noted at the time, American Apparel had managed to take on larger competitors, such as the Gap, thanks to its branding-free garments and its edgy advertising.

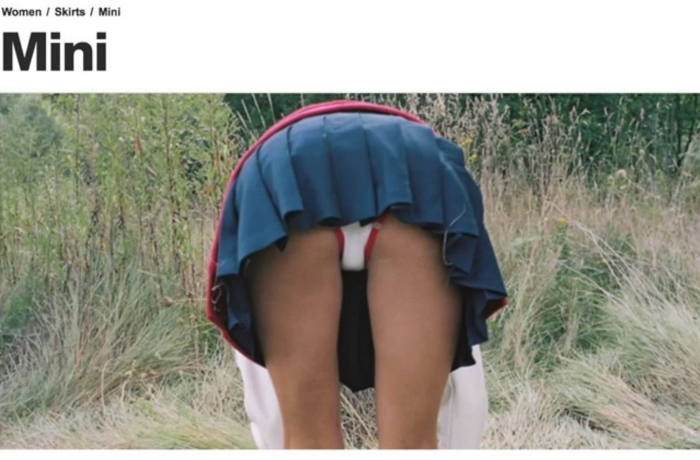

Yes, by this time American Apparel ad campaigns were thoroughly dominated by provocative young girls wearing next to nothing. A teen wearing just socks appeared in one ad. In another, a girl posed in a sheer bodysuit. Nary was there a campaign in which a model was not splayed on a bed or the floor, in a provocative pose, with barely anything on. This would become American Apparel’s aesthetic calling card of sorts.

Charney seemed unfazed by the influx of criticism that followed, calling the scandalous ads “fashionable” and “trendsetting.”

By 2007, American Apparel had become the largest T-shirt manufacturer in America. One of only a few clothing companies exporting “Made in the USA” products, it sold about $125 million of domestically manufactured clothing outside of America. All the while, the behind-the-scenes controversy that had been brewing would be making its way into the purview of the public.

That same year, the Economist published an article on the company. The first line, “Dov Charney courts controversy,” did not just refer to the company’s racy ad campaigns but the growing number of sexual harassment lawsuits filed against Charney. The article shined a light on three sexual harassment lawsuit that had been filed by former employees, alleging that Charney, then age 36, “used crude language and gestures in the office, hired women in whom he had sexual interest, and conducted job interviews in his underwear,” amongst other claims. In doing so, the suits asserted, the company’s founder and CEO was creating a hostile work environment.

Charney’s take on the lawsuits was as simultaneously bold and nonchalant as ever: “It is a testimony to my success, the fact that I’m a target for baseless lawsuits.”

From Selling T-Shirts to Selling Sex

Controversy was certainly mounting but that was not going to be reflected in a company-wide change of tune. In fact, the company’s ads became even racier and more disagreeable – Charney even made occasional cameos.

The ads, themselves, which the company’s former director of marketing and online advertising strategist Ryan Holiday, says “have been provocative and interesting from day one,” are part of the brand’s strategy to compete in a marketplace that was becoming saturated with retailers offering cheap, trend-driven garments and accessories that were being delivered to stores in an increasingly sped up timetable.

Long known for its risqué advertising, American Apparel’s suggestive ads eventually became more overt. Instead of showing a scantily clad girl, American Apparel managed to out do itself by posting online banner ads with fully topless models beginning in 2005, right around the time it started featuring porn stars, like Lauren Phoenix, Faye Reagan, and Sasha Grey, posing as “real girls.”

Of its more bold direction, Holiday, said: “We photograph models in a way that’s honest. We aren’t so constrained by the rules.”

The British Advertising Standards Authority, an independent regulator of advertising across all media in the United Kingdom, stepped in repeatedly, banning ads that it deemed inappropriate for their practice of “sexualizing” models that appeared to be underage or that were pictured in “vulnerable” or compromising positions.

American Apparel was not bothered. It also was not shy to announce that its choice of “models” were usually not actually models at all. No, these were not girls you would see walking during Paris Fashion Week. In lieu of traditional agency-signed models, American Apparel openly opted for “real girls,” ones that Charney spotted on the street or that worked in the brand’s stores. According to the company’s website, “We find our models all over the world, through online submissions, word of mouth, and in retail stores, where we’ve been known to do an impromptu test shoot or two.”

In one ad, Kelley, an American Apparel employee, is pictured posing for an array of photos, in one she wears just a thong. According to the ad’s caption, the photos were taken “by a fellow employee at the company apartment in Mexico city […] Kelley chose and re-enacted her favorite poses from vintage porn mags.” Another ad, entitled, “Pantytime,” features another female American Apparel employee, who is posing topless in bed – wearing nothing but the brand’s panties, of course.

Speaking about the company’s advertising strategy, their U.K. operations manager Brent Chase, said in a statement: “Our models are real girls who are often employees or friends of the company. The images aren’t Photoshop-ed. Sometimes, people are made uncomfortable by this, and it occasionally causes an unfortunate reaction.”

While street casting is not novel or problematic on its face, and is, in fact, utilized by an array of high fashion brands, after being pioneered largely by Raf Simons in Antwerp, Belgium, in the mid-1990’s, and the Japanese design greats before that, American Apparel took it a step further by allowing Charney to photograph the models himself.

The results were trailblazing. All of the ads shared a candid, amateur vibe – evoking the snapshot aesthetic that Lisette Model pioneered and which Terry Richardson and Juergen Teller had a strong hand in bringing to the mainstream.

A far cry from the polished, traditionally glamorous ads that big fashion houses were putting out at the time, there were no glammed up models, professional sets or recognizable faces. Instead, there were a lot of beds, couches, and white walls, and provocatively posed models that looked like the girl next door. As indicated by the British Advertising Standards Authority, the results were also highly controversial, as the ads were often “overly sexual,” “voyeuristic,” and “offensive and irresponsible.”

Controversy regarding American Apparel’s choice of models did not stop there, though, as critics began to question just how “real” its “real people” actually were. Writing for Jezebel, former model, Jenna Sauers, took a stand: “The story that American Apparel tells about its models — that they are, to a (half-naked) woman, employees, friends of Dov Charney, ‘real people’ and never professional models — is one much cherished by the company. It’s also a lie.”

It turns out, “American Apparel’s gaggle of utterly conventionally beautiful and slender women are not ‘factory workers.’ They may be ‘friends of Dov,’ but many of them do not work for the company he founded. You will not bump into an American Apparel model working the register at the store nearest you.” Instead, Sauers writes that “many are really ‘professional models,’ and some are adult film stars and actresses.” In fact, she says she is friends with a number of professional models “who’ve moonlighted for American Apparel for a quick buck.”

But as usual, American Apparel was not deterred by the criticism. In fact, it thrived on such controversy. This is something we have since learned from Holiday, whose 2012 book, “Trust Me, I’m Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator,” shed light on the brand’s tactics. In one passage, Holiday wrote: “I’d serve ads in direct violation of the standards of publishers and ad networks, knowing that while they’d inevitably be pulled, the ads would generate all sorts of brand awareness in the few minutes users saw them,” which is believed to be, at least, in part, reflective of the advertising strategy of American Apparel during his tenure.

The Brand’s Image: Hot, Young, Real

But there was something else at play. Something aside from and arguably much more important that the controversy factor that stemmed from the brand’s ad campaigns, and it tied directly to the brand’s equally as controversial staffing. American Apparel’s ads – which ultimately came to outshine the brand itself and its branding-free garments – spoke for American Apparel and the values it embodied.

American Apparel had a very precise brand identity to uphold: attainable aspiration – those hot, “real” twenty-something year-olds that appeared in the ad campaigns could be you. This was quite different from what other brands were portraying at the time. To uphold this image, employees were vetted as intensely as the subjects of its ad campaigns.

Potential employees were required to include photographs with their applications and Charney reportedly approved or vetoed each and every one. According to a 2010 report by Gawker, “CEO Dov Charney made store managers across the country take group photos of their employees so that he could personally judge people based on looks. He is tightening the AA ‘aesthetic,’ and anyone that he deems not good-looking enough to work there, is encouraged to be fired.” Speaking of the brand, Holiday told Gawker: “Every new hire contributes to our brand perception and it’s very important to the success of the company to take it seriously.”

As for the influx of criticism caused by this “sexist,” “objectifying,” and “offensive” brand image, Charney seemed unfazed. In fact, his responses usually centered on his belief the racy campaigns and the “real girl” models – as well as the “real [hot] girl” employees – were “fashionable” and “trendsetting.” And they were.

The Subsequent Fall

Despite its numerous high points, American Apparel’s affordable fashion empire has come crumbling down. In retrospect, we know American Apparel started experiencing financial difficulty prior to 2009, but that is when the retailer’s business started to go downhill in a very public manner. American Apparel was forced to accept an $80 million infusion from Lion Capital in order to pay off mounting debt and avoid bankruptcy. It paid out $5 million in order to avoid trial in a copyright infringement case that director Woody Allen filed against it for using unauthorized images of him from the movie “Annie Hall” in its advertisements. In connection with the lawsuit, Allen called the clothing firm’s campaigns “sleazy.”

Also that year, the brand became the subject of a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement investigation, which found that about 1,600 of its Los Angeles factory employees were not authorized to work in the U.S. The company would go on to fire roughly 1,500 employees thereafter. And in case that’s not enough, a letter obtained by Gawker surfaced that year, in which an American Apparel store manager said Charney would not stand for the hiring of “ugly people” as American Apparel employees.

Neither the year that was 2009, nor the resulting debt and further decline in sales, stopped billionaire investor Ron Burkle, who acquired a 6% stake in American Apparel, worth about $6 million, in June 2010. Two months later, news outlets were buzzing as American Apparel’s shares plummeted 21% and doubts about its future were at an all-time high. The Los Angeles Times, the brand’s home publication, was particularly vocal, likening the brand’s operations to those of a “madhouse” and seriously questioning “Charney’s business savvy and his ability to deal with the company’s numerous challenges.” And for maybe one of the first times, Charney was silent on the matter.

Charney’s Downfall

The situation did not look up much for Charney, personally, or for the company from this point forward. While American Apparel welcomed a new president, former Blockbuster, Inc. executive Tom Casey, in 2010, it also lost roughly $86 million that year, as well. Charney became the subject of yet another sexual harassment lawsuit and a separate racial discrimination lawsuit in 2011, both filed by former employees. That same year, the company welcomed $45 million from a group of Canadian investors lead by Michael Serruya, a prominent Canadian financier, in order to avoid bankruptcy, which appeared to be more imminent than ever. The decision not to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy resulted in board members, Mark Samson and Mark Thornton, leaving the company.

The brand’s famous founder has garnered nothing short of a Terry Richardson-esque reputation. While serving as one of the brand’s greatest strengths early on, he has fallen from grace in a major way and for the past several years seems to have done little to actually help the brand. The resounding position – amongst the analysts, at least – is that the brand should distance itself from Charney, who was very publicly suspended from the company in 2014, with its board of directors citing an ongoing investigation of alleged misconduct.

He was ultimately fired in December 2014 after an investigation found him to have engaged in inappropriate sexual behavior with employees and to have misused company funds. A clean break from Charney (or as clean as possible a break) would allow the brand to begin to build itself back up.

The Failure to Evolve

But American Apparel’s problem, the one that caused it to find itself in this less than favorable position, is not limited to Charney. In fact, it is quite multi-faceted. In short: it has considerable debt and far too little cash to keep up. As previously noted, its rapid retail expansion, which has been costly, is partially to blame. Its 227 stores, which employ something like 5,000 people, amounted to roughly 30% of the brand’s revenue. It will be in the brand’s interest to cut down, especially in terms of underperforming stores.

Moreover, the company’s manufacturing and merchandizing model has also likely contributed to its decline. As American Apparel grew and achieved an array of accolades, such as filling the slot of the largest t-shirt manufacturer in America or Charney being named an Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the Year, it followed largely the same model in terms of the manufacturing and merchandizing of goods. In fact, for many years, American Apparel offered only a couple of handfuls of different styles of shirts, sweatshirt, shorts, etc., choosing to innovate in terms of color and fabric.

First, it was the “baby tee,” then came the V-neck t-shirts, and then the colorful zip-up hoodies with their contrasting white cords. These recognizable products would become iconic items in the American Apparel repertoire – so much so that they are still being sold in stores to date.

This proved to be a strength for the brand for quite a while. In addition to the appeal of its classic American Apparel styles that consumers could count on being in its stores season after season, the price was also a sweet spot for shoppers, and thus, for American Apparel. From the start, its garments were relatively affordable; their $30 t-shirts were pricey enough that not everyone shopped there (which made it cool), but not too expensive that they alienated potential consumers (which made it profitable).

However, for the most part, it has not deviated from this strategy in any considerable way, and its model has become outdated. The brand has expanded its product offerings, but not significantly enough to truly rival the fast fashion giants that dominate the market. Instead of following a Zara model, which has the most significant hold on the market and consists of the continuous introduction of relatively small batches of different, trend-driven styles on a bi-weekly basis, American Apparel tends to dump a large quantity of more classic garments on a more traditional schedule. The result is a lack of options for young shoppers, who long for the near-constant proliferation of trend-driven garments and accessories.

In fact, its frequent sales slumps have been attributed to “a dearth of new styles,” as noted by the New York Times this year. The teen retailers that have not succumbed to this model have significantly struggled (think: Abercrombie and co.) or more or less gone away altogether (a la dELiA*s, Wet Seal, etc.).

A New Chapter

After Charney’s ouster, the company tapped Paula Schneider, formerly of Warnaco and BCBG Max Azria, to replace him in January 2015. The company also notably filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, revealing that it had not made a profit since 2009. To top it all off, the New York Stock Exchange suspended trading of shares in American Apparel Inc., and began the process to delist the stock.

But this was not the end for American Apparel. In fact, the company announced plans to keep its manufacturing operations in Los Angeles – despite some talk to outsourcing a fraction of its goods – and its 130 stores in the United States open. According to Reuters, “The big loser from the bankruptcy will be founder Dov Charney. His 42 percent stake in the company, which is held as collateral by New York hedge fund Standard General LP, will be wiped out, along with that of other shareholders.”

Under the direction of Schneider, the brand worked to right some of these wrongs. For instance, it toned down its ads. In April, it ran a “pro-women” ad on the back page of Vice magazine. The ad, which reads “Hello Ladies,” depicts various smiling employees who are fully dressed and identified by name and their start date at the company. Additionally, the ad reads: “Women have always been in charge at American Apparel. In fact, women make up 55 percent of our global workforce (sorry, guys) and an even higher percentage of our leadership and executive roles. This structure is incredibly (and unfortunately) rare in the corporate world.”

Speaking of the new advertising direction, Schneider said, “It doesn’t have to be overtly sexual. There’s a way to tell our story where it’s not offensive. It is an edgy brand. And it will continue to be an edgy brand.” And as indicated by Black Friday, when the brand’s employees were reportedly encouraged to wear t-shirts that read “Ask Me to Take It All Off,” the brand is not shedding its controversial image (or Charney, for that matter) entirely. Not yet, at least.

In fact, Charney remained on the sidelines even after his ouster. In January 2016, American Apparel, which was set to emerge from its first bankruptcy filing that month, received a takeover bid of more than $200 million from a group of investors, headed up by Hagan Capital, working with Charney. Had the offer been accepted and a deal completed, neither of which came into fruition, the plan would have been for Charney to return in some capacity to the company.

As of late January, American Apparel executives and board members regained a measure of control, with the bankruptcy court judge approving their plan to move forward with a reorganization strategy that transferred ownership of the company from shareholders to lenders, and in doing so, stripping founder Dov Charney of any stake of the company.

In terms of post-bankruptcy American Apparel, CEO Paul Schneider said the company was able to buy only about 10 per cent of the new designs it cooked up for last fall, and those designs made up only about 6 to 8 per cent of what was in stores. That should change after the reorganization, so for the spring season, she expects to bring many more new items to stores, likely 125 to 130 new pieces.

Per Fast Co., the company didn’t have enough liquidity to produce its full spring lines for 2015. She was forced to institute production-floor measures that cut overtime for factory workers (before she arrived, Schneider says, the company was spending $10 million to $15 million annually on overtime pay). She eventually closed 40 underperforming stores. And there were layoffs. Beyond clothes, Schneider has moved to close underperforming stores, trimming the chain’s portfolio from 240 locations to 204 as part of a broader cost-cutting initiative it announced last summer. Now that the closures are complete, she said the plan is to make the remaining stores easier to shop.

Schneider’s exit – which closely followed the resignation of Chairman Paul Charron, a former CEO of Liz Claiborne who had joined the board in March – came as rumors began to swirl that American Apparel was looking for possible buyers. The company hired Houlihan Lokey, a Los Angeles investment firm, to explore a possible sale, and brand licensors, Authentic Brands Group and Iconix Brand Group Inc, were among several companies reportedly interested in acquiring American Apparel if it filed for bankruptcy again.

“The sale process currently underway for all or part of the company may not enable us to pursue the course of action necessary for the plan to succeed nor allow the brand to stay true to its ideals,” Schneider wrote in a letter to American Apparel employees. “Therefore, after much deliberation, and with a heavy heart, I’ve come to the conclusion it is time for me to resign as CEO.”

Chelsea Grayson, the company’s general counsel and chief administrative officer, took the reins as CEO in early October.

Bankruptcy Round 2

As of November, American Apparel filed for its second bankruptcy protection in just over a year, weighed down by intense competitive pressures facing U.S. teen retailers and a rocky relationship with its founder. According to Charney – who has since launched a new venture of his own, aptly called Los Angeles Apparel Company – the retailer’s latest bankruptcy filing is a testament to the fact that the company cannot stay afloat without him. “This company can’t survive without my leadership,” Charney said in an interview on the heels of the company’s second filing. “They didn’t know how to run it. They took a company that could have lasted a century and crashed it into the wall.”

Separately, Canadian apparel maker Gildan Activewear Inc. agreed to buy intellectual property rights related to the American Apparel brand and certain assets from American Apparel for about $88 million in cash. Gildan will not be purchasing any retail store assets, it said in a statement.

“Gildan has asked for the opportunity to maintain certain of our manufacturing, distribution and warehouse operations in and around Los Angeles,” American Apparel Chairman Bradley Scher said in a letter to employees. Gildan will continue selling American Apparel’s basics, like plain T-shirts, to screenprinters and promotion companies. But the bid did not include American Apparel’s almost 200 stores, which were closed and their employees laid off.

The Gildan Era

As of early August 2017, American Apparel is back in business – with the company’s e-commerce site back up and running, and a new focus – on basics – at the core. Yes, the brand is redirecting its efforts with all signs point back to the staples that made it a cult classic in the first place.

And as noted by no shortage of fashion writers, everything looks quite status quo for American Apparel. According to Racked, the brand’s site is “full of old school pieces. The website invites visitors to ‘Shop the Archives,’ which features select pieces from classically racy photoshoots dating back to 2007, like the Disco pant and striped thigh-high socks. The ‘Basics Shop’ is full of just that: baseball tees, crewnecks, and colorful hoodies.”

There is one noteworthy difference at play, though. Not everything that American Apparel is offering is … well, American. Under the control of Gildan, the company has moved some of its manufacturing overseas, specifically, to Honduras, and with it, the company is making an interesting proposal for shoppers. It is giving them the opportunity to shop “Made in USA” products, as well as identical-looking ones that were manufactured overseas – but still in sweatshop-free factories, according to American Apparel.

As noted by Quartz, “Shoppers can choose between two nearly identical versions of eight of American Apparel’s signature basics, such as hoodies and t-shirts. Presented side-by-side, one version is made in the US, and the other is made outside the US. Shoppers can pick which origin they prefer, but there’s a catch: The US-made products are anywhere from about 17% to 26% more expensive.”

It is far too soon to tell whether the company’s most recent efforts will prove effective, but we do know this, the brand was not established in a way that screamed success. It got its start in a dorm room with a founder that lacked any significant business training or retail experience, and yet, borne from this humble founding was a company that has been on our radar, collectively, for the past ten years – for one reason or another.

If the brand can manage to return to its roots and focus on what it was originally known for – quality garments that are made ethically – while simultaneously staying abreast of the demands of the modern consumers, it very well may be able to regain some of the fans it has lost along the way. Because at the end of the day, who doesn’t love a well-made, high-quality t-shirt?

* This article was initially published January 2016 and has since been updated to reflect recent happening, primarily the Gildan acquisition.