A Closer Look at Vincent van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night

Pin

628

1K

Shares

Let’s take a look at Vincent van Gogh’s iconic Café Terrace at Night. I’ll cover:

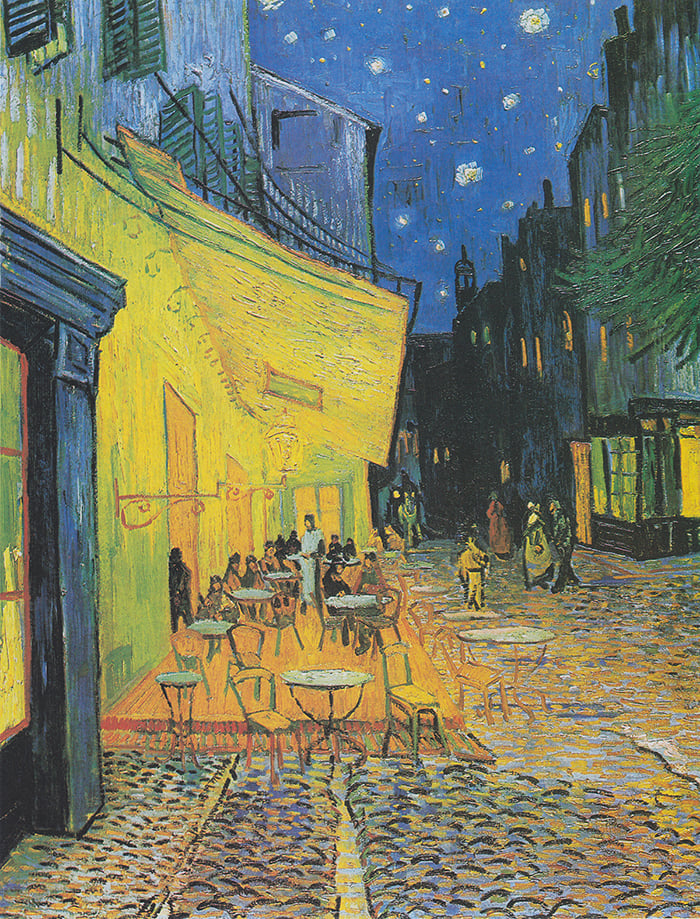

Vincent Van Gogh, Café Terrace at Night, 1888

Vincent Van Gogh, Café Terrace at Night, 1888

Van Gogh describes it well:

“On the terrace, there are little figures of people drinking. A huge yellow lantern lights the terrace, the façade, the pavement, and even projects light over the cobblestones of the street, which takes on a violet-pink tinge. The gables of the houses on a street that leads away under the blue sky studded with stars are dark blue or violet, with a green tree.” Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his sister, 14 September 1888.

Nội Dung Chính

Key Facts and Ideas

- It was first exhibited in 1891, then titled Coffeehouse, in the Evening (Café, Le Soir).

- Van Gogh painted on location. You can stand in the same spot he painted and see the café which was renamed Café Van Gogh (now that is smart marketing!).

“I enormously enjoy painting on the spot at night. In the past they used to draw, and paint the picture from the drawing in the daytime. But I find that it suits me to paint the thing straightaway.” Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his sister, 14 September 1888.

- Van Gogh didn’t sign the painting. Not sure why, as he signed most of his other works.

- The painting features van Gogh’s iconic depiction of a starry night, with deep blues and bright stars. He would continue this theme in Starry Night Over the Rhône (which he painted the same month), The Starry Night, and the background of The Poet: Eugène Boch.

- Below is a preliminary sketch of the painting. It provides insight into how van Gogh thought about the composition, patterns, and details.

- The positioning of the stars is accurate. Astronomers have since used the stars to trace the painting’s creation date to 16 or 17 September 1888 (source: Kröller-Müller Museum, where the painting is held today).

Striking Contrast and Color in the Night

“Now there’s a painting of night without black. With nothing but beautiful blue, violet and green, and in these surroundings the lighted square is coloured pale sulphur, lemon green.” Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his sister, 14 September 1888.

The painting features striking colors, as you might expect from van Gogh. Bright yellows and oranges against deep blues and greens. A powerful combination.

The colors aren’t realistic, but they work. Van Gogh had a knack for weaving vivid colors together without it appearing garish or overdone. He painted from emotion and instinct rather than relying strictly on observation. He closely observed but wasn’t bound to what he saw. Just look at the stars-he positioned them in the precise spots, yet exaggerated their appearances. That’s perhaps why his work is so special and iconic. He captured how he saw, interpreted, and experienced the world.

(A note on painting with emotion:

Every great painting needs an injection of emotion. Otherwise, we may as well just take photos. But, you don’t need to take it to the level of van Gogh’s work.

A safer approach might be to rely on observation but push certain elements that really speak to you. For example, say you’re painting a landscape with some beautiful flowers in the foreground. You might want to push the saturation of those flowers to draw attention to them, whilst staying true to observation for the rest of the painting.)

The striking contrast between yellow and blue is softened by the use of color gradation. Notice how the yellow light on the wall gradually turns green. Then that green gradually turns blue at the top of the building. That weak blue leads to the rich blue of the sky. Van Gogh is using color to lead us through the painting.

Van Gogh used black for outlining and for the dark buildings in the distance. The use of black is clever-it makes the sky look alive and filled with color by comparison.

“It often seems to me that night is still more richly coloured than the day; having hues of the most intense violets, blues and greens. If only you pay attention to it you will see that certain stars are lemon-yellow, others pink or a green, blue and forget-me-not brilliance. And without my expatiating on this theme it is obvious that putting little white dots on the blue-black is not enough to paint a starry sky.” Vincent van Gogh

There’s a strong contrast between the bright yellow and white stars and the rich blue sky. It mimics the contrast in the foreground of the bright yellow and orange café against the cool blue and green surroundings.

As mentioned earlier, van Gogh painted on location at night. I’m not sure if you have tried painting at night, but it’s a logistical nightmare. It’s hard to see what you’re painting. The colors on your palette look different. Reds don’t look like reds, yellows don’t look like yellows. You are working in the dark, both literally and figuratively. Van Gogh acknowledged this challenge in a letter to his sister and explained it was the only way he could faithfully capture the night’s brilliance.

“It’s quite true that I may take a blue for a green in the dark, a blue lilac for a pink lilac, since you can’t make out the nature of the tone clearly. But it’s the only way of getting away from the conventional black night with a poor, pallid and whitish light, while in fact a mere candle by itself gives us the richest yellows and oranges.” Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his sister, 14 September 1888.

Value (Light and Shadow)

Here’s the painting in grayscale, so we can clearly see the interactions between light and shadow:

The busy café is much lighter than the rest of the painting. So there’s contrast in both hue (yellow against blue) and value (light against shadow).

(Tip: If you really want to make a statement in your painting, overlap two or three contrasting elements. For example, thick, warm, and light against thin, cool, and dark.)

To me, the sky also looks darker in the grayscale compared to the full-color image. My eyes are confusing rich color saturation with lightness (a common pitfall in painting).

The grayscale also highlights an interesting pattern: the bottom left corner is light with dark accents; the top right corner is dark with light accents. Although some paintings, especially van Gogh’s, are best witnessed in color, it’s worth looking at them in grayscale as it often reveals value patterns you would otherwise miss.

Brushwork and Outlining

Van Gogh used blocky, linear brushwork. This in itself creates interesting patterns and character.

Notice how his brushwork follows the contours of the subjects. He used verticle brushwork for the walls, diagonal brushwork for the café ceiling, a tile pattern for the sky, and horizontal dabs for the ground. Other than that, his brushwork is roughly the same regardless of the subject’s nature (he used the same linear brushwork for the buildings as he did the sky).

He made use of outlining to reiterate forms. Look at the chairs and tables, the edges and detailing of the buildings, and the people wandering the streets. Edgar Degas used a similar technique, painting with flat planes of color plus strong outlines to depict form.

You can see van Gogh’s brushwork up close in this high-resolution photo of the painting. You should also take a look at this Google Arts and Culture page. (Note: There seem to be numerous photos of the painting with vastly different colors. I haven’t seen it in person, so it’s difficult to say which is the most faithful to the real thing.)

Composition

The architecture in the painting provides a strong sense of perspective. Notice how the edges converge towards a vanishing point on the horizon line (which is hidden behind the buildings). Cityscapes like this are perfect for conveying linear perspective. It’s harder in landscapes, where you are mostly dealing with organic shapes.

(Tip: It’s always good to lean into the natural traits of the subject. If painting a linear cityscape, lean into the lines and perspective. If painting an atmospheric landscape, lean into the depth; make those distant blues a touch blue-er. I learned this from Steve Huston.)

The dark doorway on the left and the dark buildings on the right frame the sides of the painting. They contain our attention on the light areas around the middle.

The busy café is the focal point, but it doesn’t dominate the painting. It’s competing against the night sky’s rich blues and bright stars.

Below is the painting with a three-by-three grid over the top (created using my grid tool). Some key observations:

- The corner of the café ceiling comes to the top horizontal.

- The people gravitate around the bottom horizontal.

- The cafe is off-center to the left.

- The two verticals roughly mark the start of the sky on the left and the start of the buildings on the right.

(Refer to my post on the rule of thirds for more information.)

Key Takeaways

- Can you use any recurring themes in your work? Like the starry nights in several of van Gogh’s works.

- Van Gogh painted with both observation and emotion (leaning towards emotion). Consider how you can incorporate emotion into your work, without departing too far from the subject.

- Be careful not to mistake highly saturated colors as being lighter than they really are.

- Looking at a painting in grayscale can reveal interesting patterns that you might have otherwise missed.

- Let your brushwork follow the contours of the subject.

Want to Learn More?

You might be interested in my Painting Academy course. I’ll walk you through the time-tested fundamentals of painting. It’s perfect for absolute beginner to intermediate painters.

Thanks for Reading!

I appreciate you taking the time to read this post and I hope you found it helpful. Feel free to share it with friends.

Happy painting!

Dan Scott

Draw Paint Academy

About | Supply List | Featured Posts | Products