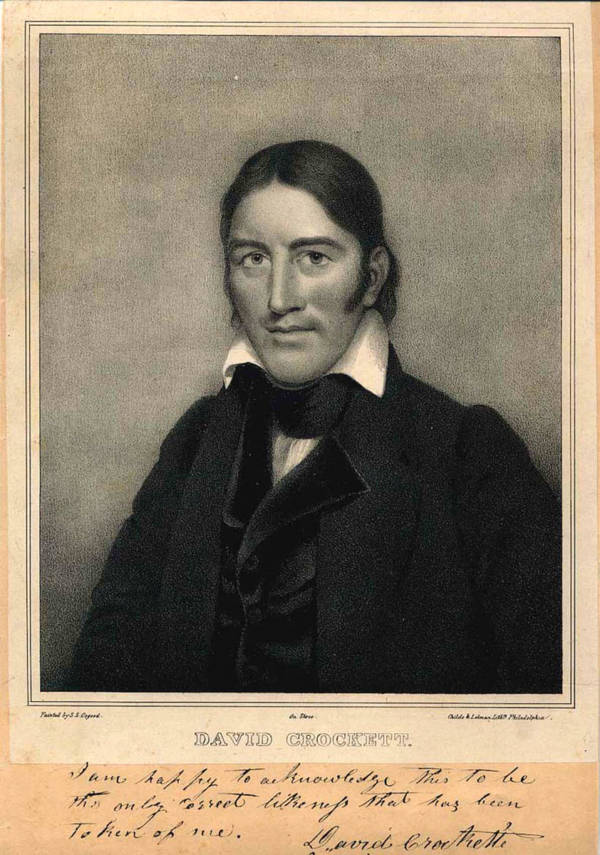

Davy Crockett, The Storied Frontiersman Of Early 1800s America

Nội Dung Chính

Known as the “King of the Wild Frontier,” soldier and adventurer Davy Crockett became a folk hero for his exploits in the Creek Indian War and the Texas Revolution.

To this day, America remembers Davy Crockett as a frontiersman and a folk hero, part myth and part man. His explorations were dramatized in stage plays and storybooks for decades, and his name conjures images of wilderness and coonskin caps.

But who was the real David Crockett, the man behind the tall tales and the popular mythology?

Born in Tennessee in 1786, Crockett survived a grueling childhood in which his own father sold him into indentured servitude, before serving in the state militia to fight against the Creek Indians.

But then, in a move that rarely makes it into the legends, Davy Crockett went into politics, first in the Tennessee legislature and then as a congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served for six years.

And after his days in Washington were over, Crockett returned to the battlefield, where his story came to its fittingly mythic conclusion. In 1836, after joining in the Texas Revolution, Crockett died at the iconic Battle of the Alamo.

From the well-known highlights of his story like these to the things that rarely make it into the history books, this is the full story of Davy Crockett.

Davy Crockett’s Rough-And-Tumble Early Years Before Heading To The Frontier

Born in Tennessee in 1786, David Crockett had an unconventional upbringing. His father, John Crockett, was plagued by rotten luck. After being forced to sell his land to make ends meet, losing his newly built gristmill to a flood, and declaring bankruptcy on his second home, John Crockett moved to a property owned by John Canady, to whom he was now deeply indebted.

When Davy Crockett was 12, his father sold him into indentured servitude in an effort to pay off the Crockett family’s debt. For several weeks, Crockett worked as a ranch hand for a man named Jacob Siler in Virginia.

The labor was hard, but he was fed well and treated fairly — that is, until the job was done, when Siler tried to force the young Crockett to stay on. The boy escaped at night through knee-deep snow and made his way back home to his family in Tennessee.

He wasn’t destined to stay long. The next year, when the boy was 13, his father enrolled him in school with his brothers — but the high-spirited Crockett quickly got into a fight with another student.

To avoid getting into trouble from his schoolmaster, Crockett started skipping school. When word of his absences made its way back to his father, he knew he was in for a whipping — one he had no intention of taking. Instead, he packed up his things and went back to Virginia, where he joined a series of cattle drives to support himself.

After a few years, Crockett returned to his family, but he had grown so much that they almost didn’t recognize him. When they realized who he was, they welcomed him back with open arms, and the boy agreed to stay on and work with his father to help relieve the family’s debt.

He returned to indentured servitude with John Canady, and then, debt-free, stayed on for an additional four years to build his savings for his next adventures — or, rather, misadventures: Davy Crockett fell in love.

Crockett’s Tempestuous Love Life And First Forays Into Battle

It was a productive time for Davy Crockett: in the following years, he would fall in and out of love four times and father six children.

He first fell in love with Canady’s niece, but she was engaged to Canady’s son, and his romantic pursuit ended badly.

It was at her wedding that he plunged into love a second time, this time with Margaret Elder, who liked the spunky young Crockett — but not as much as she liked her other fiancé, for whom she broke her marriage contract with Crockett in 1805.

Finally, Crockett met Mary Polly Finley, who was not engaged to anyone else, and they married on August 14, 1806.

His life with Mary was quiet and respectable. He bought land alongside his brother, started a family, and worked on the same cattle ranch he had worked on as a young man. And then he got itchy feet.

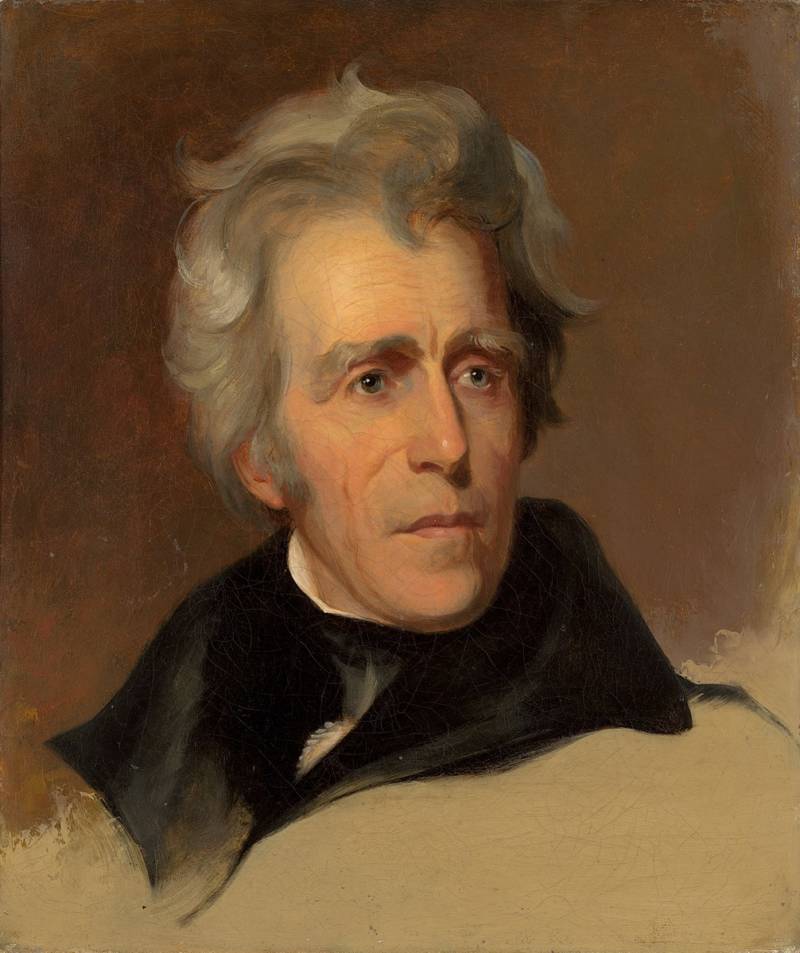

In September 1813, Davy Crockett decided to join the war that General Andrew Jackson and the Tennessee militia were waging against the Creek Indians, enlisting as a scout for a term of 90 days. The conflict took him to Alabama, where he saw action and considerable bloodshed.

Crockett shone — but not as a warrior. His skills were in hunting and foraging, and his talent for turning up food and navigating the wilderness won him friends among the militia. When his term was up, he decided to reenlist, further delaying his return to his family to fight in the War of 1812.

He finally returned home in December of 1814, but his reunion with his wife was brief. She died within the year.

With three children to look after, remarriage was a matter of urgency for Crockett. He wed the widow Elizabeth Patton, who already had two children of her own, and together the pair had three more children.

And still Davy Crockett was unsatisfied with domestic life. In 1817, he moved with his family west to Lawrence County, Tennessee, where he thought he’d try his hand at a career in politics.

Davy Crockett Goes Into Politics

Davy Crockett rose quickly through the ranks — but his journey was plagued by restless uncertainty. In a span of just two years, he became a justice of the peace, then commissioner of Lawrenceburg, and then lieutenant colonel of the Fifty-Seventh Regiment of the Tennessee Militia.

But he gave all of these positions up, citing the need to spend more time attending to his businesses and family.

The truth, however, was that he was restless again. Not long after he resigned from his post with the regiment, Crockett was back in a political race, pushing for a seat in the Tennessee General Assembly. In 1821, he got his seat, and just three years later got another one in the United States House of Representatives.

His mission was to fight for the rights of poor settlers, who he felt were at the mercy of a complicated and arbitrary system of land grants that threatened their way of life and left solvency always just out of reach.

His determination to fight for the rights of the poor but numerous farmers of Tennessee made him a popular candidate, and he won reelection handily — until his opposition to Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act threatened to ruin everything.

Of his decision to vote against the act, Crockett wrote:

“I believed it was a wicked, unjust measure… I voted against this Indian bill, and my conscience yet tells me that I gave a good honest vote, and one that I believe will not make me ashamed in the day of judgment.”

While the 21st century recognizes the justice of Crockett’s position, his district didn’t. He lost reelection but, undaunted, clawed his way back to the House of Representatives two years later.

Crockett’s Outsized Mythology Slowly Begins To Take Root

As a politician, Davy Crockett was determined not to be a stuffy one. During his time in the House, he tried his hand at several other hobbies, including the dangerous business of manufacturing gunpowder.

The hobby that consumed most of his time, however, would also become his most famous: big game hunting.

In the woods of Tennessee, Davy Crockett found fame hunting black bears and selling their pelts, meat, and oil for a profit. He claimed that between 1825 and 1826, he killed 105 bears. It was this claim, as well as his fondness for hunting other dangerous game, that made him the frontiersman people know him as today.

He began to appear in comics and short stories, and tall tales about his accomplishments grew taller in print.

He entered the national consciousness in an 1831 play that took his life as its subject, though it called its frontiersman protagonist “Nimrod Wildfire.” Though the play never referred to Crockett by name, there was no doubt he served as its inspiration.

He fed his growing mythos by publishing his own accounts of his adventures in an 1834 autobiography, a text designed partly to set the record straight and partly to act as the impetus for a kind of book tour that would see him campaigning outside the state in what many thought might be a bid for the presidency.

But it all became a moot point when he unexpectedly lost his bid for reelection to Congress — cutting any chances of taking his campaign national short.

Crockett, never one to make idle threats, made good on his promise to head for Texas if his constituents didn’t want him. He was out of the country before Martin Van Buren was even elected.

How Davy Crockett Died A Hero At The Alamo

Davy Crockett never meant to join the fight for Texas’s independence, but the restless frontiersman never could resist a cause.

He fell in love with the land almost immediately, describing it as a paradise and a settler’s dream.

In a January 1836 letter, he wrote:

“I must say as to what I have seen of Texas it is the garden spot of the world. The best land and the best prospects for health I ever saw, and I do believe it is a fortune to any man to come here.”

He died just two months later fighting in the Battle of the Alamo, and the newspapers were flooded with dramatic — though entirely unsubstantiated — tales of a brave end. In death, as in life, he continued to be as much myth as he was man.

The true story of his end emerged in 1975, 140 years after the battle, when the diary of a Mexican lieutenant was discovered. His account painted a heroic picture of Crockett, whose sharpshooting had taken out a number of enemies and only narrowly missed the Mexican general, Santa Anna.

Crockett was captured in the early hours of the morning as Mexican troops broke through the Alamo’s fortifications. He was taken captive against Santa Anna’s orders; when the general found out he had been taken alive, he and his companions were immediately executed.

The Mexican lieutenant reported Davy Crockett was courageous even at the end. Curiously, his account of Crockett’s final hours echoes the tall tales spun back home by men and women who imagined a hero’s death without seeing it — bringing a strange kind of truth to the end of one of America’s greatest myths.

After learning about David Crockett, check out these amazing photos of the American frontier. Then read about Peter Freuchen, another man whose true story sounds like a tall tale.